April 17, Easter Day C (John 20:1-18)

Mary has no hand to clutch or shoulder to lean on.

One of my favorite things about living in Southern California was driving down the Redondo Beach Esplanade on a clear morning. I loved seeing the impossibly blue ocean and the pure white spray of the breakers. I marveled at the curve of the land, how the Santa Monica Mountains and the Palos Verdes Peninsula stretched to embrace across the Santa Monica Bay.

What I loved most of all was the chance to observe the people standing on the Esplanade sidewalk, taking in the seascape. As I kept one eye on the road and one eye on the coast, I caught fleeting glimpses of people who were utterly transfixed by the ocean. Something about being in the presence of something so vast and deep just enthralls people. I’ve heard it said that gazing at the ocean actually causes one’s soul to expand. The soul grows in response to what it sees.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

John’s resurrection narrative casts the reader as a witness to the witnesses. The focus of this story is on the ocean, so to speak, but also on the people whose souls are expanding in response to its beauty. The Gospels do not even begin to imagine what went unwitnessed that first Easter morning. Barbara Brown Taylor notes that “the resurrection is the one and only event in Jesus’ life that was entirely between him and God.”

I think we’re better off keeping it that way. I once watched a video marketed to churches for use in Easter worship. A man wrapped in linens lay on a table. As an orchestra played dramatically in the background, the man slowly began to stir. The music billowed to a climax as the man sat up. I hated it. It reduced a miracle to a cartoon, a holy mystery to a crude farce. Worst of all, it forced the Easter celebration back into the tomb.

John’s story begins and ends with Mary Magdalene. She alone makes the mournful journey to the grave of her Lord. In the other Gospels, other women accompany Mary to the tomb. But here she is alone. She has no hand to clutch or shoulder to lean on as she discovers, in horror, that the stone has been rolled from the tomb.

At this point in the text, there is a lot of floundering chaos—and it is no surprise, for this is what often happens when Jesus goes missing. Mary turns and runs back to the disciples to proclaim the bad news. They run back to try to make sense of the strange turn of events. All that is left in the tomb are the linen wrappings that had bound the lifeless body of Jesus. They take in the sight—the utter emptiness of the tomb—and turn to go home, mired in confusion.

Mary remains. All she knows is that her Lord is dead and that someone has salted her wounds by robbing his grave. She stands vigil in front of the vacant tomb, her soul contracting in the presence of such cataclysmic absence.

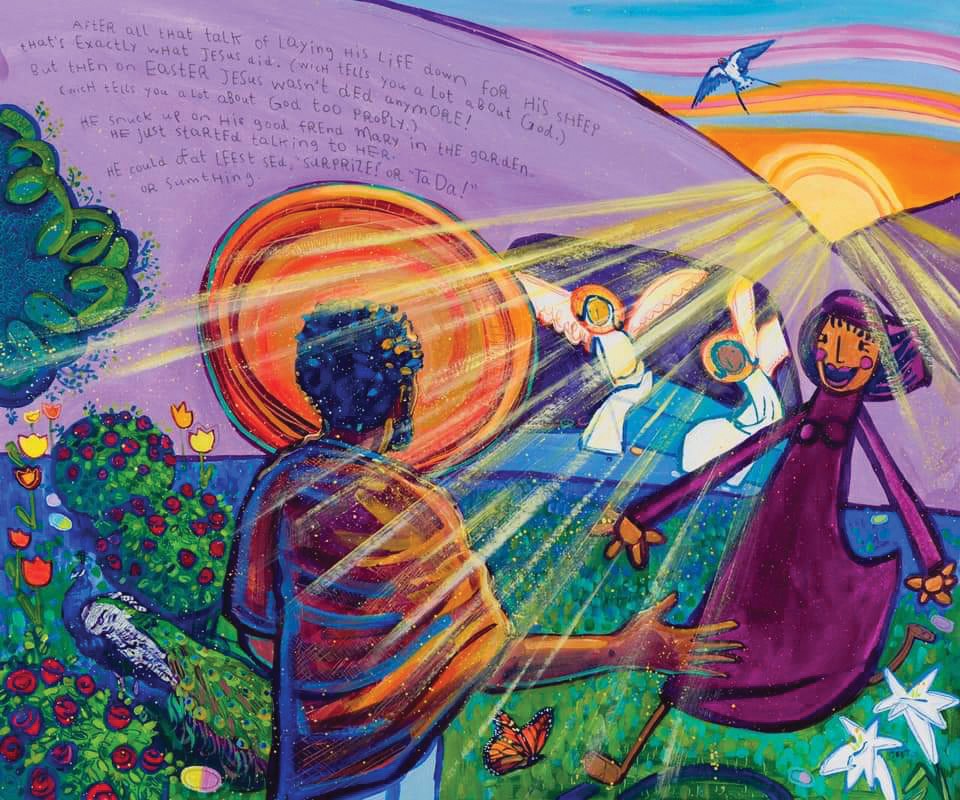

I have been meditating on this scripture through a painting by Joel Schoon-Tanis, included in his book 40: The Gospels. Art is, after all, oceanic in its capacity to enlarge our souls. Schoon-Tanis is a Michigan artist who paints biblical stories and pairs them with childlike commentary that is often phonetically spelled. In the paintings, Jesus is depicted painstakingly, in a sophisticated and detailed brush style. So, too, are a smattering of flora and fauna. But most of the figures—including all of the non-Jesus humans—are rendered as if by a child, with stick limbs and rudimentary faces. Jesus is set apart; he is Word and light, way and truth and life.

If the paintings weren’t so whimsical and endearing, perhaps Schoon-Tanis’s theological anthropology would feel heavy-handed. In the Easter morning scene (above), happy angels are perched in the entryway of the tomb. The sun is rising, the roses and lilies are blooming. An exquisitely detailed monarch butterfly flits by Jesus, whose back is turned to the viewer. In every painting his back is turned; you might catch a fleeting glimpse of his face as he stands utterly transfixed by the person in front of him. This time, it’s Mary. And though she was bereft mere moments before, her guileless round face is giddy with delight. Schoon-Tanis writes, “[Jesus] snuck up on his good frend Mary in the garden. He just started tawking to her. He could of at leest sed, ‘Surprize!’ or ‘Ta Da!’ or sumthing.”

This random gardener just starts “tawking” to her, and at first he is unrecognizable. But then he speaks one word that reveals everything to Mary. One word is all it takes for her to believe and understand, to break into joyous worship: her very own name.

Encountering the Risen Christ expands one’s soul, even without a proper “Ta da!” I am praying that, like Mary, I might have just enough faith to keep weeping until I hear my name.