Making old things new

Great artists know that the past provides essential ingredients for the future. Jacob Collier exemplifies this. So does Jesus.

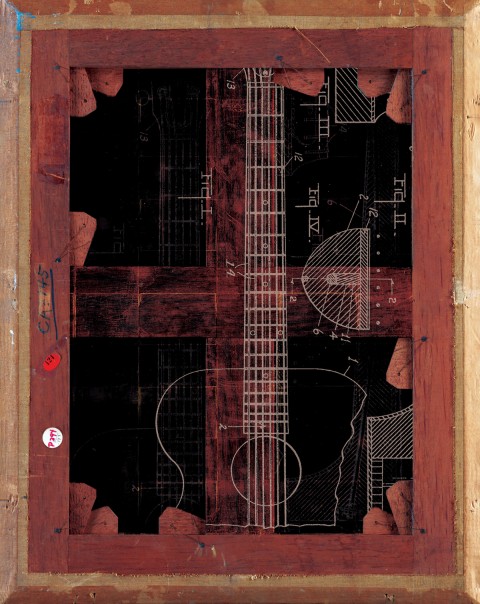

Century illustration (Source images: Public domain and Met Museum, NY)

When musical savant and multi-instrumentalist Jacob Collier found himself stymied by the guitar, he walked away for a time. Then he came up with his own approach to the instrument. He removed the first string—the highest-pitched one—and then learned to play on the remaining five in an alternate tuning. This narrowed his choices—which had the counterintuitive effect of opening new harmonic horizons. For example, it made it intuitive to play an unusual and hauntingly beautiful chord. “It’s one of my favorite chords ever,” Collier gushes in a YouTube interview with Paul Davids, “and I would never play this chord if it wasn’t for this guitar.”

It’s a lesson in remembering the thread. The point of a guitar, after all, is to make music. There are many moving pieces—taut strings on a thin piece of wood, a fretboard to navigate, fingers to strum or pluck with, and more. With so many technical details, it can be easy to forget the point: All of it is in the service of harmony and melody.

If it takes audacity to tweak an instrument that’s been around for centuries, there is also an inherent humility. “On any instrument, there is no objectively good technique for everyone,” he says with openness and generosity. But he is no maverick paving a lone path, so he quickly adds, “There are also core principles.” For Collier, innovative technique rests on foundational principles. And for anyone who has listened to his unusual music, the result is a blurring of boundaries with an almost transgressive quality.

It is reminiscent of Jesus’ jarring effect on his hearers and his tendency to push and prod beyond inherited boundaries. For example, in John 2, standing before some Sadducees, Jesus talks about tearing down the temple, adding the astonishing assertion that he would rebuild it in three days. It’s just about the worst possible thing he could’ve said at that moment, because the Sadducees were keepers and leaders of the temple, their most prized sacred site.

In John 3, Nicodemus comes to Jesus—likely because he, being a Pharisee, has just enjoyed watching Jesus put the rival Sadducees in their place. But Jesus tells him more or less the same thing he told them: Forget everything you think you know, and be born again. Jesus knows that not all temples are physical buildings.

In John 4, Jesus encounters a devout woman of Samaria and engages her in vigorous theological debate, not unlike his conversations with the Sadducees and Nicodemus. He declares that God is moving beyond the site of her people’s cherished tradition around Mt. Gerizim.

Over and over again, Jesus challenges his interlocutors, destabilizes their settled ways, and invites them to a new path—in a way that makes old things new, even as it also ties the past to the present. Pádraig Ó Tuama puts it this way in “Prayer for a New Name”:

We do not destroy past names,

because they have brought us here.We celebrate the new name

that will bring us on.

Such fecund wisdom from poets and other artists offers badly needed guidance for our trying times. Even if there must be a reckoning with yesterday, they tell us, tomorrow is always a new day. The past provides essential raw ingredients for the future.

A few weeks ago, I found myself unexpectedly stranded in Selma, Alabama. In the middle of a pilgrimage of sorts, I stayed behind with a student who fell ill while the rest of the bus continued. What was to be a brief, overnight stop turned into three days. At first, it was the small things I noticed: no Lyft, Uber, or DoorDash. More seriously, there were no rental cars, not even in nearby Montgomery. Walking around the Pettus Bridge, a storied site of titanic struggle in this country, there were faint signs of a complicated history and vague plans for renewal, but mostly a haunting quiet. I also had some of the most amazing human encounters, replete with warm southern hospitality, at a nearby hospital that provided excellent care despite evident staffing challenges.

It was also a good time to watch Jacob Collier’s music videos, especially a version of his song “Little Blue” recorded in an empty cathedral. There in that hollow, cavernous space, with the help of a diverse choir of mostly young people, the singing is mighty enough to blow the roof off the place. It is a scene of resplendent glory restored, with sounds surely unimagined by the original builders.

Sometimes there is beauty in this world that hits you in the face out of nowhere. Melancholy can do that, too. And then there are the times when contradictory emotions collide all at once.

Listening to “Little Blue” in Selma had this effect on me. As I thought about the history of racism and its awful entanglement with Christian faith in this country, while stuck in a city that bears so many visible scars of that past, my heart vacillated from revulsion to sadness to longing to gratitude for chance encounters with deep humanity. As I listened to a chorus of discordant voices singing a strangely beautiful song played on an odd five-stringed guitar, I heard notes hauntingly familiar and foreign, aching and comforting, mixing anguish and hope. It’s a spiritual experience I will not soon forget.