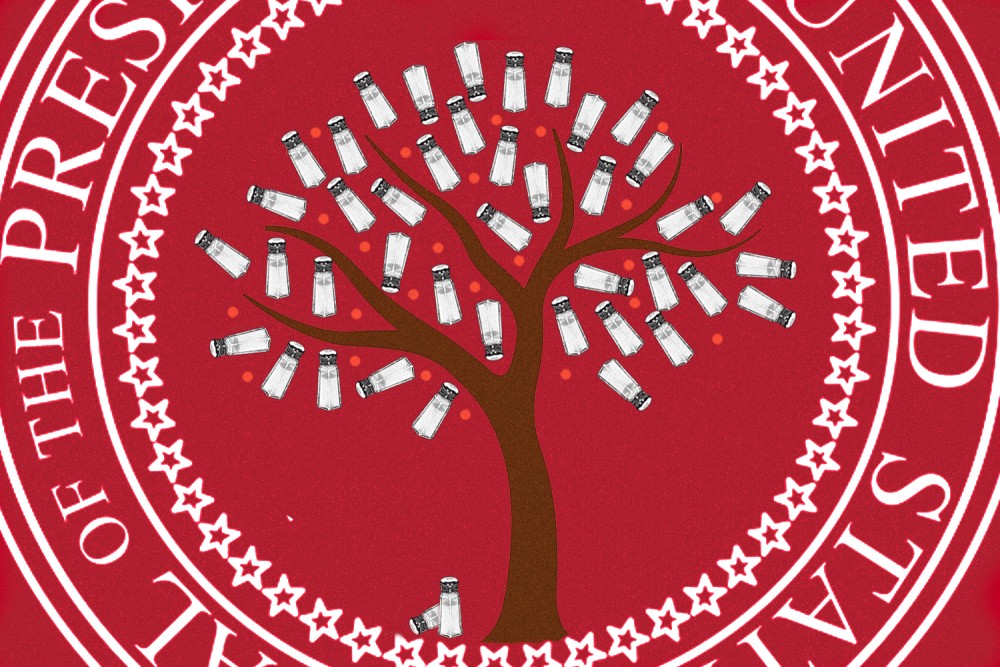

You will know a tree by its salty fruit

Franklin Graham cares about Trump’s language. So does Jesus, but for very different reasons.

“The president, his pulpit—his microphone—is huge, and it carries a lot of weight,” he told Deseret News. “So I’m going to continue to try to encourage him. He’s not just the president of this country. He is a world figure that other nations, other presidents, other people, look up to and want to emulate. … That microphone goes a long way.”

Finally! A little righteous anger from a Christian Trump loyalist. And what’s the cause of this anger from the president of Samaritan’s Purse, an organization devoted to evangelism and international disaster relief? Is it Trump’s isolationist rhetoric and slashing of global aid? His disparagement of immigrants and refugees? His hard lean into fascism?

Nope. For Graham, the issue is simply Trump’s “salty” language.

“Your storytelling is great,” he wrote in a private letter to the president, “but it could be so much better if you didn’t use foul language.”

Really? That’s the problem here? He uses impolite language, but this bears no connection to his ideas, which are great?

What the $%#?!

This isn’t the first time Christians have been concerned with the way Trump talks. In 2019, after Trump used the phrase “god damn” at a rally in Greenville, NC, Paul Hardesty, a Trump-supporting West Virginia former state senator, received phone calls from constituents angry about Trump “using the Lord’s name in vain.” Hardesty then sent a letter to the White House to both pledge his support to Trump and ask him to mind his language.

“I am appalled,” Hardesty wrote,

“that you chose to use the Lord’s name in vain on two separate occasions. … There is no place in society—anywhere, anyplace and at anytime—where that type of language should be used or handled. Your comments were not presidential. I know in my heart that you are better than that.”

I’ve heard similar sentiments from Christian Trump supporters over the years. They’ll say things like, “I don’t love the way he talks, but he has a heart for the country.” My own family members send letters like Graham’s to the White House asking Trump to knock it off with cussing. For these folks, the bad language is merely accidental; it doesn’t go to the heart of who Trump is.

This would be news for Jesus, for whom language is an issue of the heart. “Each tree is known by its fruit,” says Jesus.

For figs are not gathered from thornbushes, nor are grapes picked from a bramble bush. The good person out of the good treasure of his heart produces good, and the evil person out of his evil treasure produces evil, for out of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaks (Luke 6:44-46).

Jesus is remembered quite frequently for caring about his followers’ language. He warns against speaking “careless words” (Matthew 12:36) and insulting a brother (Matthew 5:22). He seems pretty serious about it: To call someone a fool, he says, is to risk hellfire. He also instructs us not to take oaths and to say what we mean and mean what we say. “Let what you say be simply ‘Yes’ or ‘No’; anything more than this comes from evil” (Matthew 5:34-37).

For Jesus, language is a vehicle to communicate love and truth and wisdom. Words can bring healing and comfort. We can use words to construct stories about the Kingdom of God and to invite people to join in the fun. Words also give us the opportunity to criticize injustice, to pronounce woe on those acts that violate God’s standards of love. Words, then, are incredibly powerful. They affirm and jeopardize life, bless and curse. By them, we are either justified or condemned.

Over the years, plenty of scholars have tried to locate the true words (ipsissima verba) of Jesus in the various gospel traditions. Cutting away what they determined to be later editorial flourishes, these scholars homed in on what they decided were the real words of Jesus. The trouble with this, as contemporary historians note, is that it is almost impossible to reconstruct the “original” words of Jesus. What we have in the gospels are various memories of Jesus’ interactions with friends and enemies—memories that have been re-remembered and reconstructed over time. This doesn’t mean it’s impossible to paint a convincing picture of a “historical” Jesus. It just means that we have to shift our focus from Jesus’ exact words to the kind of Jesus that is being remembered in the language of the gospels.

When we keep an eye out for affect, what we are confronted with on every page of the gospels is that Jesus had a habit of making people feel a certain way. When they were in his presence, they felt cared for—even those whom he was reprimanding; as Jesus’ own Hebrew scriptures put it, you only correct someone you love (Proverbs 3:12). Jesus’ words for many people were life-giving and loving. His words healed them, sometimes physically. In the tradition of the prophets, Jesus used his words to remind his people that God was, all appearances to the contrary, still with them and was going to act on their behalf quite soon. Jesus’ words gave people hope. Whether or not we can reconstruct exactly what he said, we have convincing reasons to believe that Jesus spoke in the way the gospels portray him speaking.

What’s most striking about what the gospels have Jesus say is that his words are always so poignant, so beautifully fitting to the moment at hand. When someone needs mercy, he speaks mercy. When someone needs challenging, he speaks criticism. When someone needs a little humility, he gently pulls the rug out from underneath them. “A word fitly spoken,” says a proverb, “is like apples of gold in a setting of silver.”

Like Graham, Jesus is concerned with our language. Unlike Graham, Jesus believes that our language speaks us, that our words give people a clue about the kind of beings we are and about the kind of god we submit ourselves to.

It is possible, then, to look at Trump’s salty language and, rather than see it as Graham does, to believe that it tells us something important about who Trump is. He has a certain way of talking, of using words, especially words directed at people he doesn’t care for—migrants, Democrats, judges who believe in the rule of law. It seems that the point of Trump’s mean language is for it to feel mean. In other words, Trump’s salty language is very much an important part of his personality and his presidency. It can’t be dismissed.

What’s most remarkable to me about the Christian criticisms of Trump’s salty language is that the same people seem not to care about the way Trump talks as long as he doesn’t swear. But his meanness, his pettiness, his knack for insults—aren’t these things unfitting to a Christian? Shouldn’t they also be unfitting to the American presidency?

It doesn’t seem that those Christians who voted for Trump agree with me. They’ve been listening to him talk for a decade, and they’ve decided that the salty bits are, well, maybe a little embarrassing, but not really an issue. I know I won’t be able to change their minds.

What I do want to suggest is that Jesus cares very much about our way of being in the world, a way of being that includes a way of talking. We should use our words to affirm life, to communicate love, and to share wisdom. Likewise, we should avoid using our words to disparage people, to praise our own power, and to threaten the vulnerable.

Jesus’ followers will be known by their fruit.

Oh, and for the record, some fruit tastes better with a little salt.