January 7, Baptism of the Lord (Mark 1:4-11)

Each January the lectionary invites us to remember the invisible network of faith.

Some years ago one of my parents was diagnosed with cancer. It was a routine, treatable cancer, but the very word, the C-ness of it, frightened me. Driving home I called a friend whose parent had died of a different cancer, and she patiently walked me through the worst-case scenario.

My parent would get sicker and sicker and need help doing things one would never want or imagine having one’s child do because it seems too embarrassing or intimate. But we’d get beyond that. I’d do the things such that they would become routine, and we’d find moments of macabre humor. And then my parent might die. And if that happened, my friend finished, I would become part of the population of children whose parents have died.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Years and treatments and clean scans later, I think of my friend’s statement: that there is a vast network of people whose parents have died, a tribe of sorts that exists and that someday I will join. I don’t think of it in any aspirational way, just as a matter of simple fact. There is a band of people with a shared experience all around me, and in time I too will know what they know and be one of them.

In my less harried moments, sometimes I wonder what secret networks the people I pass on the street are part of—the people who have run marathons or written plays or taught someone else to drive or had a sibling with special needs, the people who donated blood yesterday or live with an eating disorder. What is that network like? Emerson describes a “language of wandering eye-beams” among people who silently honor one another in some sort of shared experience.

Telling you about this, I am just now remembering walking with my grandmother on the sidewalk. It must have been summer. She was wearing one of what she called her camp shirts: short-sleeve, button-down V-necks in various pastels and floral prints. She insisted upon those shirts up until the end, even when the buttons became vexing to her palsied hands and her children alike. A man, rather grizzled looking, passed us and then called out, “Hey, you too?” and pulled down the collar of his T-shirt to reveal a vertical white scar at his collarbone. Flustered, my grandmother hurried me along. She didn’t like strangers, much less chatty ones. But I asked what the man meant, and she explained that they’d both had open-heart surgery. That was fascinating to me, that older people recognize others with their same physical realities just like kids do, like someone else with a skinned knee or broken arm or missing front tooth with a little space they can put their tongue in as a badge of pride.

“In baptism,” writes Michael Rogness in his Working Preacher commentary on this week’s Gospel reading, “we become part of a people.” Each January the lectionary offers us the baptism of Christ and invites us to remember the network we hold in common: a people who believe that when the heavens open in the beginning of Mark (or Matthew), God is doing something new. God already split the waters of the Red Sea with Moses and the Jordan River with Joshua, Elijah, and Elisha. But by splitting the heavens, God is going back earlier, to the beginning when the earth was separated into day and night, form and void, heavens punching out into the firmament above and the sea below, back to that originality—and laying claim to Jesus within that. In the rite of baptism, that same elemental water touches us and initiates us into the tribe of people who believe in Jesus’ Messiahship.

What does it mean to be part of that confessional collective? It is a worthy question in any year but particularly in this one. In any given year people will have become parents or widowers or spouses or graduates or unemployed. This year, many became for the first time protesters and canvassers and questioners.

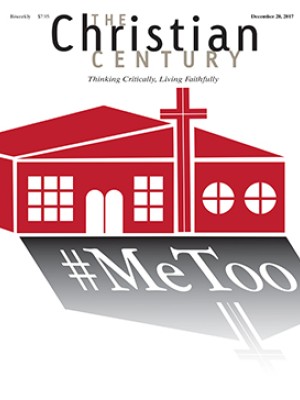

This was a year of awakenings for so many. We have circled around yet again to ask whether health care, education, clean water, sustainable earth, nuclear peace, racial equality, and trust in first responders are goods we hold dear. We have begun to ask as well whether affordable child care and sexual consent and addiction treatment and economic equality and careful control of powerful weapons are also goods we ought to hold dear, dear enough to put money and policy behind them.

Being a baptized people in this moment means we are invited to think of our collective confession—as every age before us has done, yet also uniquely in this moment. What will our resolutions be for this year ahead as the tribe of the baptized, as those identifiable to one another as people who believe that God did a new thing in Jesus?