The academy needs better theologies of cooking

The first step is to give voice to those whose work in the kitchen is shaped by necessity, not choice.

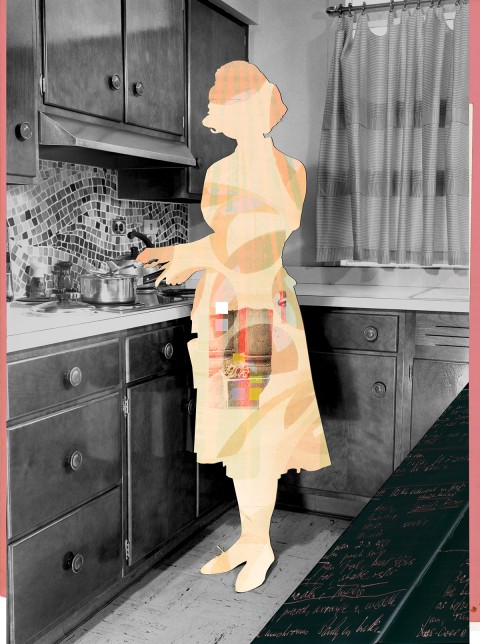

Century illustration (Source images: Getty)

Last year, a doctoral student studying theology and food reached out to ask me for my thoughts. “There is so much writing on agrarian theology,” he said. “And a lot on the table, but almost nothing on the steps that happen in between—on cooking. Why do you think that is?”

It’s a question I first posed at a food and faith conference in 2015, while still a young graduate student in food studies, debating whether or not to take the step into the world of theology.

“The field is young,” I was told then. “One step at a time.”

When I did decide that studying theology was the right move for me and focused my research and writing on a theology of bread and baking, the truth became a bit clearer.

There has been a vast amount of writing on theology and cooking over the years. Women have for centuries been meeting God, drawing near to God, and having their understanding of God shaped through domestic labor. But by and large, this work has not been taken seriously within the theological academy. Cooking has historically been considered the purview of women, and women’s work has not historically been valued as work worthy of rigorous academic exploration. As men have chosen to start cooking more, a theology of cooking has begun to emerge. But I would argue that we need a kitchen theology written out of the experience of those whose cooking is shaped by necessity, not choice.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

There is a unique form of theological wisdom gleaned through the process of cooking. This is wisdom that women who have written on theology and domestic labor have been trying to illuminate for centuries. The 17th-century nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz summarized this wisdom most succinctly in her well-known quip, “If Aristotle would have cooked, he would have written a good deal more.”

The student I spoke with was right: there is a huge dearth of academic work being done on the topic of theology and cooking. Looking at trends in food media over the past two decades, and how they have impacted trends in food and theology conversations, I predict that academic theology will continue to show a greater interest in the topic of cooking. But I fear that it will be an interest in cooking abstracted from the actual people who have been responsible for cooking for most of human history.

To understand my fear, and to propose what I believe is the remedy, we need to understand the historical origins of the present discourse on theology and food.

In 2006, Michael Pollan released the book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, transforming the ways Americans talk about food and agriculture and launching a genre of food writing that food historian Megan Elias calls the “food origin story.” Pollan encouraged readers to know the origins of the foods they eat, and out of that knowledge to choose what they purchase responsibly. “In the discourse of origins,” writes Elias in her book Food on the Page, “the right kind of knowledge restored pleasure to consumption.”

Pollan’s work built on an interest in localism that had been growing in the food industry since the natural food movement of the 1970s, and it followed two popular investigative works on the fast-food industry—the path to the book’s launch paved by a growing sense of unease with the sources of our food. Though Pollan was not the first to write about the ills of industrial agriculture, his work positioned him as the prophet come to wake readers up to the systems they are a part of.

As Elias details, Pollan’s book invoked “sorrow for the ecological impact of pesticide use . . . sorrow for the loss of nutrients . . . sorrow for the impact on the ozone of machinery that processed [produce], and the trucks that distributed [it], even perhaps sorrow for the cook and diner who were too ignorant to use local organic [food].”

This shift in national conversation about food created the perfect opportunity for agrarian theology to take root, providing a Christian response to industrial agriculture, one that expanded on the writings of Wendell Berry. Ellen Davis’s Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture came out in 2009, followed by Norman Wirzba’s Food and Faith in 2011 and Jennifer Ayres’s Good Food: Grounded Practical Theology in 2013.

A little more than a decade later, numerous seminaries and divinity schools now offer courses, and in some cases even certificates and full degrees, in food. These writings were the springboard for many scholars, myself included. If not for Wirzba’s work, I would never have even considered a degree in theology—I was fully set on a career in the restaurant industry and traditional food media.

Missing from these writings, though—as noted by the student who emailed me—is an account of the cooking required to transform the ingredients acquired through this nonindustrial agrarian vision into dishes that readers can then eat. This creates two major gaps in the literature: first, a gap in recognizing the additional labor necessitated by this agrarian theological vision, labor typically assumed to fall to women. And second, a gap in celebrating the human creativity and connection across time and place this cooking inspires.

By overlooking the domestic labor of women that is integral to our food system, the present theological discourse on food also overlooks the concerns of women that shaped the very industrial food system Pollan’s narrative decries.

The industrial advances of the 19th century challenged the place of women in society. As technology historian Ruth Schwartz Cowan outlines in her book More Work for Mother, emerging technologies replaced the bulk of men’s domestic labor (namely, farm labor), making men the natural choice to leave the home and enter the workplace. This shift from farm to factory lightened the load for women in some ways, as many of the household necessities previously made from scratch by women in the home—things like butter, soap, candles, and clothes—were now available for purchase.

At the same time, it created a monotony in the lives of women. Their daily lives consisted of cooking, feeding, and cleaning, along with mending the products purchased with the money earned by their husbands. This rhythm of maintenance was, as food historian Laura Shapiro writes in Perfection Salad, “in a tangible sense unproductive.” The concept of work became defined by the earning of money—something done by men outside the home—while women’s labor was viewed as “an extension of [her] existence, one of her natural adornments.”

“As women’s traditional responsibilities became less and less relevant to a burgeoning industrial economy,” Shapiro continues, “the sentimental value of the home expanded proportionately.” A renewed version of that same sentimentality can be seen in the food origin genre that emerged a century later.

Moralist writers like Catharine Maria Sedgwick, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, and Catharine Beecher wrote novels and theological treatises that depicted the home, and with it the kitchen, as an extension of heaven, a counterbalance of the world of industry and commerce that men engaged in during the day. For some of these writers, the vision developed from these writings was an honest depiction of what they understood their work to be. At the same time, these publications provided the opportunity for them to engage in the professional realm—using their traditionally feminine work of cooking and cleaning as a way into the professional world of men. In the case of Phelps, theological writings were an opportunity to respond to the writings of her father and grandfather, both biblical scholars who she believed were blind to the ways domestic labor forms the “living fabric of Christianity,” in Shapiro’s words.

Phelps’s writings depict a world in which the wisdom of women, gleaned through their work in the kitchen, shocks and upends the assumptions of clergymen. In this way, it parallels the writing of Sor Juana two centuries before, whose theological work so challenged her bishop and confessor that she was forced to abandon her academic pursuits and return to the convent kitchen instead.

The moralist writings of the late 19th century paved the way for the domestic science movement of the early 20th, as women fought to have their day-to-day labor taken seriously in the academy. Eventually renamed “home economics,” the field of domestic science was formed by women further fighting for a place in the professional realm. They argued that the keeping of the home could be most successful if approached through the lens of science, with the rigor and objectivity assumed to be the purview of men. The very desire to be taken seriously in the academic and professional world inspired women to approach cooking through the ideals of sanitation and control. The home economists and food reformers of the early 20th century taught women to prioritize precision in their shopping, getting the most nutrients for the least amount of money and discarding any cultural or sentimental attachments to flavor.

By teaching Americans to relate to cooking and eating in a purely rational sense, these food reformers also taught Americans to celebrate the industrial agricultural system that unfolded in the coming decades—a true feat of engineering and transportation.

I find it to be no small irony that women pining to be taken seriously by men in academia a century ago helped craft the narrative about food that is disparaged today. And in that disparaging rhetoric and the vision for a better way, the work that has historically been assigned to women continues to remain invisible.

I found a home in the field of food studies in 2013 while healing from a long history of disordered eating. For years, I was able to mask my harmful relationship to food through the quest for “clean eating.” By citing concerns with my hormonal health, I was able to opt out of the industrial food system and limit my definition of “safe foods” without raising much alarm. When I was finally ready to confront the reality that my dietary norms were masking something more dangerous, I turned to history, anthropology, theology, and culinary science to guide my relationship to food. The interdisciplinary field of food studies provided the space to hold together the complexity of our food system, and individual relationships within it, resisting the simplified narratives that writers like Pollan put forth.

Because of this history, I entered into the discourse on food and theology with a degree of skepticism. I pursued theological education with the desire to fill in some of the gaps left by the invisibility of women’s labor. I became fascinated by the writings of women like Sor Juana, Phelps, Ada Maria Isasi-Diaz, and Kathleen Norris, women who recognized that God reveals God’s self in a unique way through the monotonous labor of caretaking. It’s what Norris calls “the quotidian mysteries.” More recently, Kat Armas’s Abuelita Faith has joined this canon of writing on the wisdom formed out of women’s labor traditionally overlooked in the academy.

During my own academic tenure, I faced similar resistance to the food reformers of the early 20th century. I found boundless support for the tangible fruits of my labor—excitement for the actual bread that I baked and the workshops on baking and intentional shared meals that I taught within the church—but because this side of food production is coded as feminine labor, I faced a much harder time gaining support for the intellectual fruits of this work.

“You don’t really work in theology and food,” a colleague once told me when I expressed frustration at the resistance I faced. He contrasted my work with our fellow classmates who were engaging closely with agrarian trends in theology. “You’re more focused on eating and the table.”

“Well, there’s more to food than growing it,” I retorted.

The summer that my male colleagues devoted to writing their theses, studying for the GRE, and applying for doctoral programs—all of them with working spouses who cooked, cleaned, and financially supported them along the way—I spent developing recipes for a local popsicle shop and nannying for a woman writing her dissertation. As a single person, I couldn’t afford not to work full time, and in my off-hours, I was responsible for all of the labor of managing my home alone. There was no time left over to write my thesis early enough to allow me to apply for doctoral programs that year.

Over the next year and a half, while continuing to discern whether and how to continue in the academy, I nannied for two more academic moms, getting an up close look at the reality of being a woman in theology. I was grateful for the ability to confront the unique limitations that would accompany me in this work—limitations my male colleagues never had to consider.

These experiences shaped my writing in profound ways. The necessity of forming my life around the demands of cooking, cleaning, and domestic labor expanded my understanding of how God forms us and is present with us in the kitchen. And yet, the very experiences that fostered such profound intellectual thinking also limited the time I (and the women whose families I cared for) could spend actually engaged in the activities that afford one success in the academy.

Now that men do more cooking at home, there is a growing interest in the theology of cooking. But will the writing that emerges reinforce existing gaps?

In 21st-century American families, it is increasingly common for men to participate in the domestic labor that has historically been ascribed to women—even more so among families outside the cis-hetero norm. To those who regularly shop, cook, and clean for their families, my theological concern here might ring hollow. But the historical context in which our experiences are formed matters to the kinds of intellectual arguments we make. It is unlikely that most of the men who are cooking in their homes today were raised with the assumption that they would be the primary food preparers in their homes. Girls have typically been taught that they must learn to cook to provide for a family, while boys have been taught that if they can cook, they will impress others. That difference is integral to how we as adults relate to and write about the process of cooking.

Now that it is considered normal, or even cool, for men to be the primary cooks in their homes, there is a growing interest in the theology of cooking. While I’m grateful for this turn, I am concerned that without proper understanding of the gendered history of the field, the writing that emerges will reinforce the gaps that have long existed. Theological writing on cooking must wrestle with the factors that influence what people cook and why, and under what conditions. It must look for the wisdom that emerges in the kitchen as opposed to the classroom or at the computer.

Any theology of cooking that is worth engaging ought to start from a place of understanding the wisdom and limitations of those for whom cooking is a necessity and not just a choice. Ironically, though, those limitations are exactly what prevents the wisdom of many in this position from being recognized in the theological academy.

Just as womanist theology is born out of the understanding that Black women have a unique experience that lends them particular insight into the things of God, just as mujerista theology recognizes the wisdom emerging from the position of Latina women, kitchen theology should be written by those who have lived under the expectation that they will provide for themselves and for others, those who have watched the fruits of their labor get thrown on the floor by a screaming toddler, those who have skillfully prepared shopping lists for tight budgets, picky palates, and limited storage, by those who do not have the financial means to purchase prepared foods and must cook to sustain themselves and their household.

This theological framing is not exclusively for those who live in this reality (though I would hope it could be written and dispersed in a manner accessible to them), but it is from that position. This is also not to say that writing on the topic of theology and cooking ought to be limited to those from this position. It is, however, to say that any theology of cooking ought to begin from listening to the wisdom of those who have written out of this place. It ought to begin from a recognition of the distinct irony and privilege of being able to write about cooking through an academic lens.

The boundaries of such necessity are not as clear-cut as the boundaries of the womanist and mujerista discourses from which I draw this model. While it is predominantly women who are shaped by this experience, it is not exclusively women. And while Black and Latina women have historically been employed (or enslaved) as domestic laborers in the United States to liberate White women from the demands of cooking and cleaning, the experience of cooking out of necessity is not limited to people of color, either.

When I received that initial query from the doctoral student, I spent a few days debating how to respond—first working through the many conflicting emotions I carry into this conversation. I congratulated him on the opportunity to write about cooking within the academy. This is, of course, a vital step in developing a more robust discourse on theology of cooking. I encouraged him to look to the writings of women over the past century and the ways we have been taught to relate to the act of cooking and eating. I advised him to avoid the temptation to sentimentalize or to think of cooking as an action abstracted from the larger realities in which women prepare food for others and for themselves, even if that abstraction might benefit him academically. To do so, I warned, would lead to a theological account that is not only harmfully biased but also misses the full depth of theological wisdom that cooking (and those who have historically been responsible for it) can lend to the field.

In order for writing on theology and cooking to truly mine the depths of how this work can shape our knowledge of God, it must begin with those whose relationship to cooking has been shaped by this necessity and not solely the privilege of choice. And it must account for the irony that this necessity is in itself a factor that limits their presence in the field of theology in the first place.