Evangelical fantasies in Amish country

I grew up in the Quiverfull movement. In the tourism industry of Shipshewana, Indiana, I see a lot that looks familiar.

Illustration by Martha Park

Shipshewana, Indiana, is home to fewer than a thousand people and the Midwest’s largest flea market. It only takes a few minutes to drive its main street, bordered by signs advertising Amish furniture stores and locally made meats and cheeses. The town has all the makings of a Lifetime Christmas movie: historic houses, quaint shops that close by 5 p.m., and a beautiful landscape of farm fields and wooden barns. LaGrange County, together with neighboring Elkhart and Noble Counties, is also home to the third-largest Amish community in the United States. Shipshewana’s tourism industry relies on it.

The Blue Gate Restaurant and Theatre is at the center of town, a sprawling white building with cobalt blue doors. Tourists arrive by the busload to eat at the buffet of fried chicken, buttery mashed potatoes, cinnamon apples, and chocolate cream pies. Servers wear Plain clothing—long-sleeved, modest dresses in solid colors, the women’s attire of most Amish and some Mennonite communities. It’s all part of the experience for those who want to enjoy a good old-fashioned country meal served by smiling women in good old-fashioned clothing. After dinner, people often linger at the Blue Gate to enjoy entertainment at the performing arts center, which hosts national music acts as well as family-friendly plays such as a musical adaptation of Janette Oke’s When Calls the Heart.

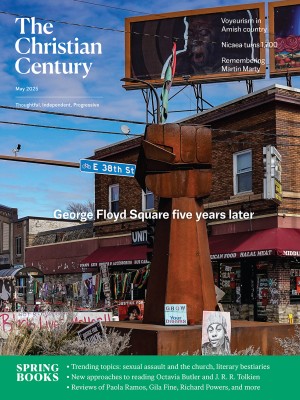

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A while back I spent a day in Shipshewana with friends. We did some holiday shopping at the flea market, and before heading back to Michigan we stopped at the Blue Gate for dinner. While we waited for our table, I became distracted by the products for sale, which made me feel like I’d stepped into a Family Christian Store in the early aughts: white dinner plates and wooden signs bearing scripture verses, children’s books like God’s Wisdom for Little Girls and devotionals like A Little God Time for Men.

As I browsed the titles, the red flags of Christian patriarchy flew before my eyes. Everywhere I turned, I saw the evangelical mission to convert and keep the sheep in the fold. It was all too familiar, but I was confused. Why were evangelical books being sold in an Amish context, when Plain communities are known for their intentional isolation from mainstream society? I noticed that some of the servers were wearing eyeliner and lipstick. This made me wonder whether some Plain people wear makeup, or whether some of the servers were simply dressing the part for the benefit of the tourists. What was I missing, as someone who was raised in fundamentalist evangelicalism? What was really going on here?

When I saw an advertisement for an upcoming play at the Blue Gate Theatre that pictured an Amish man standing on the front lawn of the White House, I knew I had to return and investigate.

Josiah for President the musical is based on Josiah for President the novel, written by Martha Bolton and published by Zondervan in 2012. The story centers around a politician named Mark Stedman who has become disillusioned with the corruption in Washington, DC, and is calling it quits after an unsuccessful run for president. But on his way home, he accidentally drives into a ditch in the middle of Amish country. An Amish farmer named Josiah Stoltzfus helps him—and introduces him to his family and simple way of life. In response, Mark starts to think that maybe what the country needs is a man like Josiah for president. An unprecedented campaign ensues.

I had no idea what to expect when I sat close to the center of the auditorium to watch the play on a moderately booked Thursday night. The rest of the audience seemed to be made up of elderly folks, and I thought of church groups traveling on buses for a night on the tiny Amish town. As I settled in, I wondered whether Amish community members would be allowed to watch a play like this.

What starts out as a cheesy musical—a song called “Leak It,” to the tune of Michael Jackson’s “Beat It,” is about spreading gossip on political opponents—quickly begins to veer into misogynistic territory. The other presidential candidates are a career politician who naively listens to his rumor-spreading female assistant and a beauty-queen-turned-governor who has had four husbands. When she’s asked by a reporter how she balances work and family, I rolled my eyes. Of course, the only woman politician is portrayed as a failure, I thought. Even the female reporter is portrayed as overly ambitious and lacking a dating life.

But there are two women the play presents in a positive light: Mark’s wife, Cindy, and Josiah’s wife, Elizabeth. Both are supportive of their husbands, helping them from home. But while Cindy is raising her kids in a consumerist society, Elizabeth is calm, soft-spoken, and focused on her household duties. She’s given Josiah many children—though none appears on stage—and she cooks three homemade meals a day. When Josiah decides to enter the presidential race, she says, “I go where you go. That is my choice.” I couldn’t help notice this language, because it is how I was taught to understand patriarchy: that women are choosing to submit and follow their husband’s leadership, even though their choices are in reality quite limited.

She’s the perfect Quiverfull wife, I thought. Compliant. Apparently willing to be perpetually pregnant in order to live a godly life. I grew up in the Quiverfull subculture of evangelicals, a strictly patriarchal group that prioritizes having as many children as possible. And Bolton’s novel uses familiar Quiverfull language. When Mark first meets Josiah’s family, he receives a short lesson in Christian patriarchy:

Three children, all dressed in typical Amish clothing, were playing in front of the house.

“Your kids?” Mark asked, as they moved up the driveway.

Josiah smiled and nodded. “My quiver is full.”

“Quiver?”

“It’s a Bible thing.”

“Guess I missed that part,” Mark said, noting to himself to look it up later.

“It means I’ve been abundantly blessed with children. Mary Ann’s inside helping her mama in the kitchen. She’s our teenager.”

Recognizing the vocabulary of the particular evangelical world I grew up in made me wonder: Is this language that Plain people use? Or is it just a bleeding in of evangelical culture from the book’s evangelical author?

Abuse survivor and advocate Mary Byler, who was raised Amish, confirmed for me that the latter is the case: “That’s not language that we would have used. . . . But they talk about [how] children are a blessing from God.” Byler pointed out that Pennsylvania Dutch is many Amish people’s first language, perhaps explaining why they don’t use an English term like quiverfull. Yet many of their beliefs about women’s roles in society are the same.

Byler grew up in Old Order Amish communities—known for their rejection of modern technology—including some in the particularly conservative Abe Troyer Amish subgroup. Byler wrote about their experiences in their book Reflections and Memories of an Amish Misfit. Calling Josiah for President “the epitome of evangelical stereotypes of what it means to be Amish,” Byler explained that in this story, “Amish women are dehumanized, they are fetishized, they are objectified, and Amish people in general are dehumanized and fetishized and treated as objects.”

This resonates with my experience of growing up Quiverfull, where women are objectified and treated as the property of their patriarchal leader. So it made sense that this trope of the Amish woman as compliant and subservient would show up in an evangelical novel.

Watching the play, I experienced cognitive dissonance as I contemplated a portrayal of an Amish woman as content in her limitations. Plain communities, although decentralized, are run by patriarchal rules. The act of submission inside a patriarchal society amounts to a complete lack of agency, and when Elizabeth says she chooses to follow Josiah, we can understand that she has very few options.

But the dangers of patriarchy and the lack of women’s agency don’t come up in Josiah for President. Instead, Josiah runs on a campaign of going “back to basics” and “good old-fashioned values” in a sort of nostalgic, pre-Trump Republicanism. If only Americans worked hard and stayed close to God, the country would be better off. And when Josiah becomes president, for a time the country does seem to thrive. He shuts off the electricity in his private quarters and starts a farm on White House grounds, Americans across the country start farming again, and—in perhaps another nod to Quiverfull—birth rates are on the rise. Paired with the song lyrics “I like big beards and I cannot lie,” the results of an Amish man being elected seem unrealistic if not absurd.

Growing up surrounded by fundamentalism, I know this is just the sort of fantasy an evangelical might dream up: a simple man of God returning the nation back to an imagined past of simple goodness. Many evangelicals don’t see a problem with the patriarchal culture of the Old Order Amish—in fact, patriarchy is precisely what draws them to fetishize these communities. So in Josiah for President, patriarchy is shown as benevolent; the narrative is not complicated by patriarchy’s harms.

But the fantasy does turn dark. Shortly after being elected, Josiah is assassinated. His last word to his wife is, “Forgive.” Mark Stedman, who had been the vice president, is now sworn into office: he’s achieved his dream of becoming president after all. All he needed to do was exploit an Amish man to get to the top.

And all this play needed to do was make a few jokes about butter churning, throw in the occasional jah or gut, and overgeneralize about an incredibly diverse collection of religious communities in order to spread a White evangelical message that has flourished in US politics in recent years. While neither the book nor the play overtly calls for Christian nationalism, Josiah does leave a black leather Bible on the desk in the Oval Office. Josiah is just another example of the Amish being objectified, oversimplified, and exploited for an evangelical message.

Beyond the Christian nationalist implications, plays like Josiah for President and venues like the Blue Gate Theatre are part of a much larger industrial complex. According to the documentary Sins of the Amish, “Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, alone attracts around 8 million visitors per year and generates nearly $2 billion in economic activity.”

To better understand the Amish tourism industry, I contacted Jasper Hoffman, an advocate and host of the Plain People’s Podcast. She calls the facade of Amish tourist hubs “Disneyland.” In our conversation, she pointed me to a darker side to the industry: Amish- and Mennonite-run facilities that serve as troubled teen homes and rehabilitation centers for sexual predators. These facilities are often places where Amish goods are created, the same goods that are sold in tourist towns like Shipshewana. Hoffman said these goods are the products of child labor, that Amish butter is “salted with the tears of children.”

She went on to describe how the romanticization of the Amish, which fuels the tourism industry, “endangers every single child that’s in those churches. It makes it so much harder for people to believe that the abuse rates are as high as they are. Old Order Amish and Mennonite communities have done such a great job branding and marketing themselves, and they know exactly what they’re doing.”

For Hoffman, the abuse rates are not just numbers on a page. She became a conservative Mennonite at the age of nine after Anabaptist faith spread through her homeschool community in Northern California. When she was a teenager, her community punished her with isolation for a year and a half because she had exhibited signs of nonconformity with the group. On one occasion, she was able to get a horse, despite the community rule that girls weren’t allowed to have horses. This inspired other girls in the community to put up posters of horses in their rooms, only to be severely beaten for their disobedience.

Hoffman experienced suicidal ideation, self-harm, eating disorders, and trichotillomania—a mental health condition marked by compulsive hair-pulling—which she says is a common disorder in Plain communities because it’s easy to hide under head coverings. Her mother secretly took her to a mental health center in a different county for treatment, where a therapist helped her realize she could leave the community and be OK. She eventually did just that and now dedicates much of her life to helping survivors from abusive Amish and Mennonite communities.

And there are many survivors in need of services. Mary Byler, the survivor I spoke to about the play, told me that child sexual abuse is extremely common in Plain communities, but because of their isolation, there is limited research on abuse within Anabaptist contexts. Byler’s advocacy is fueled by their own experience of years of sexual abuse perpetrated by boys and men in their family. Byler told me, “I get reports of Amish youth and people who are survivors of sexual abuse and child sexual abuse who died by suicide. I’ve been listening to the stories of child sexual abuse coming from within Amish settlements since I was 12 years old. I am now 40. We cannot address what happens within a patriarchal, authoritarian, high-control religious group when they are covering up abuse, and aligning themselves with perpetrators of abuse and protecting them at all costs to protect the organization, unless we actually name it.”

When the crime of sexual assault occurs within a high-control religious group, reporting it is often viewed as a greater sin than the assault itself. Instead, forgiveness is preached as the godly response. But as Byler told me, “forgiveness is something that involves silence.” I am reminded of a powerful line from the film Women Talking, which tells a story of Mennonite women determining their own future: “Is forgiveness that’s forced upon us true forgiveness?”

The dynamics that both Hoffman and Byler described to me are the same conditions for every high-control religious environment that I have studied. As abuse survivors, we understand the power and control dynamics of abuse—and how these dynamics set up the vulnerable, especially children, to be harmed.

The next time I visited the area, I was reading from my memoir at Fables Books in Goshen, Indiana. Two fellow authors joined me in a conversation with readers about religious trauma and purity culture. Fables co-owner Kristin Saner made us feel welcome and gave us space to share our stories and connect with local readers as part of Goshen Pride Week. She was wearing an “only pride, no prejudice” T-shirt.

I was surprised to learn that Saner is a Mennonite—a progressive one. This made me realize I had a lot more to learn about the Anabaptist tradition. My perception of Mennonites had been shaped almost entirely by the Old Order sects, a preconception only ever confirmed by the evangelical media I had been exposed to. I hadn’t ever met another progressive Mennonite.

I talked to Saner about this later. She grew up United Methodist but joined an Anabaptist church after marrying someone who had been raised Mennonite. They wanted to raise their child in a community of faith, and Saner was drawn to the values of pacifism and social justice activism held by many Mennonite Church USA congregations. Unlike the churches that Byler and Hoffman had been part of, Saner’s church in Indiana has two women pastors and accepts LGBTQ people fully.

Of course, patriarchy still exists there, just like in most churches. “Anytime you get a group of people together, you have the potential for hurt,” said Saner. “It hurts me when I find out that abuse has happened. If victims decide to leave, I don’t blame them. Power can lead to abuse. Open communication is the only way to move forward.” Saner’s church has policies in place to protect vulnerable people from abuse, including training for mandatory reporting and how to work with law enforcement to report crimes. This is very different from the Old Order Amish and conservative Mennonite communities I learned about. Instead of covering up and enabling abuse, it seems that abuse is taken seriously in Saner’s community.

I wish all faith communities could be so prevention-minded, but too often it seems that systemic hierarchies in churches only silence victims and enable abusers. When I share my own story of abuse in the church, I am often met with well-intentioned believers’ response that it’s “not all churches.” And while I understand that we cannot broad-brush an entire religion, it is important to assess where theology and church structures are creating an environment that enables abuse. Until this is no longer a problem, we survivor-advocates will keep calling attention to it.

The morning after our event at Fables, my author friends and I had breakfast at an Amish restaurant in a neighboring town. The restaurant was mostly empty at 10 a.m. on a Monday, and I saw rows and rows of tables that might well be filled with tourists at busier times. Instead, at the table next to ours was seated a large family dressed in Plain clothing, enjoying a late breakfast together. Most of the seats were filled with children, and I remembered my own experiences with church potlucks, the children outnumbering the adults. As I sat down, I felt my chest tighten with anxiety. Something felt off to me. I looked over at their table again, and the two little girls at the end of the table were staring at me, mouths slightly open. There was no shame in how they peered at me over their plates, only curiosity and perhaps, I wondered, shock.

In a place where Amish and Mennonite people are used to being gawked at for their non-modern clothing, I had become the object of fascination. My shorts, my forearm tattoo, my dangling earrings—the way in which I now show up as myself—communicated an individualism that I never had the freedom to truly express as a child in a fundamentalist home. I smiled at the girls, trying to communicate a neutral compassion—not pity, not shame. And they continued to stare. Although I had spent so much time trying to understand a community that is so different from (and yet familiar to) the world where I grew up, I could not read their thoughts. I could only wonder if they would ever break away from the patriarchal lifestyle they were given. As I sat there wondering, the family got up from their seats and left the restaurant.

The people I met in Indiana and the survivors I interviewed taught me that Anabaptist communities exist on a spectrum of isolation and freedom—and that they are far more complex than the typical evangelical novel or play cares to explore. And in this leveling of a religion and culture, we so often miss the darker underbelly of any community in which children and women lack agency over their lives. Ironically, it is the evangelical gravitation toward patriarchy that makes it so hard for them to recognize patriarchal abuse. No number of romantic adaptations will make me comfortable with a world in which oppression is propped up as godly.

Josiah for President gets much wrong about the Amish. An Amish man would more than likely be shunned for running for public office, and Amish family life does not necessarily include the joyful submission of women and children who are content with their limited options. Isolation, limited education, and a purity culture—along with a protected leadership with little accountability—are the ingredients for systemic abuse to thrive, and Plain communities are not as ideal or safe as the well-marketed tourism industry would have us believe.

Amish and Mennonite tourism seems to be fueled by the same sort of voyeurism that inspired entertainment from my own fundamentalist past. With the rise and fall of the Duggar family, of 19 Kids and Counting fame, I’ve watched as people accept easy stereotypes of those of us who grew up in the Quiverfull movement. Shows like this focus on the “wholesome” lifestyle and ignore the obvious problems with lack of consent, especially when it comes to the children being exploited. When we help turn a religious group into a curiosity for our entertainment, we so easily forget that these groups are made of very real people.

As Byler said, “Plain people are human beings, not objects for gratification. Human beings with human issues.”

____________________________________

The Century's community engagement editor Jon Mathieu discusses this article with its author Cait West.