Understanding Czesław Miłosz

Eva Hoffman, a fellow exile from Poland, writes about the Nobel-winning author like no one else could.

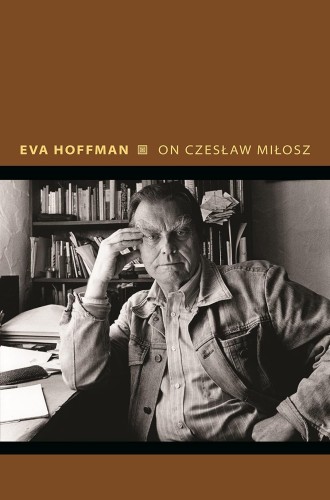

On Czesław Miłosz

Visions from the Other Europe

This illuminating study by novelist, historian, and critic Eva Hoffman is a literary biography of the Polish Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz. One of the greatest writers of our time, Miłosz captures in much of his writing the intensities of a violent century of war and the terrors of authoritarian regimes. A Catholic who helped to shelter Jews, he writes about the Holocaust, but he also writes about the loneliness and longing of exile, reaching back into memory of the particulars of his early life. “It is possible,” he mused in his 1980 Nobel lecture, “that there is no other memory than the memory of wounds.”

Hoffman, who grew up in Kraków, knows well the life of exile. She emigrated to Canada and now teaches in London. This biography of Miłosz contains many of her own personal reminiscences. She knew Miłosz as only another Polish writer could know him, as she has known other Polish Nobel laureates. That makes this book, written from a fresh new angle, both distinctive and trustworthy. She summarizes Miłosz’s complexities this way: “From an obscure Lithuanian hamlet to San Francisco Bay, from historical past to the hypertechnological future, from the Bible to pop culture—Miłosz’s range was enormous, and his need to grasp it all came close to a kind of torment.”

Hoffman juxtaposes Miłosz’s experiences of the world into which he was born (the “other Europe” of the book’s subtitle) with his life at Berkeley and trips through Middle America, where he found both Bohemians and evangelicals and refused to choose between them. Hoffman cites his account of meeting with a “young simpleton” who asked “how life in Sacramento differed from life in a concentration camp.” Miłosz insisted that America was not a comfortable place for him, but he showed both admiration and compassion for Americans. Poland was “all past,” he observed, and America “all future,” which meant that, predictably, America lacked historical perspective.