For better or for worse, the church is keeping Haiti afloat

In the absence of strong political leadership, someone has to fill the void.

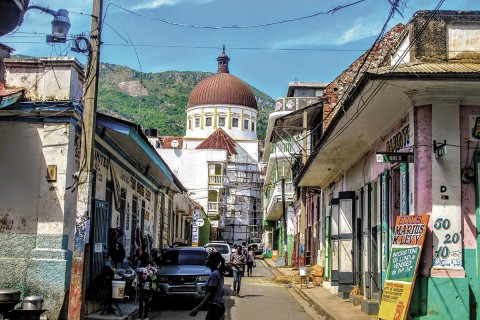

When societies lack good governance and social stability, churches and clergy often fill in the gaps. In some cases, notably in modern Africa, church leaders can become something like kingmakers. In the Western Hemisphere, the nation of Haiti exemplifies the pivotal role of Christian churches in politics.

The nation was born in the 1790s from the incredible turmoil of the great revolt of an enslaved population and the decades of war and devastation that followed. Famously, Haiti has always retained its African religious heritage in the form of vodun, but the great majority of the people also asserted their faithful Catholic roots. Most recently, evangelical and Pentecostal churches have boomed, partly as a consequence of the new forms of faith Haitian migrants encountered when they set up homes in US cities such as Boston and Miami. Today, Protestants (mainly evangelicals) make up some 30 percent of the country’s 11 million people, compared to 55 percent Catholic and 10 percent nones.

Haiti’s modern history has witnessed many disasters, both human-driven and natural. From 1957 through 1986, the country was ruled with appalling tyranny by the Duvalier family, and more recent regimes have often been deeply unstable. The results of the 2015 election were so controversial that they were eventually annulled, as extensive popular protests and demonstrations became an endemic fact of life. Last year, Haitian president Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in still unexplained circumstances. The country is by far the poorest in the Western Hemisphere, with 60 percent of Haitians living below the poverty line; it is also marked by extreme wealth inequality. As if these horrors were not enough, a 2010 earthquake killed 300,000 and devastated the capital, Port-au-Prince.