The book of Job is a parody

Sometimes I picture its author looking down at us and shaking his head.

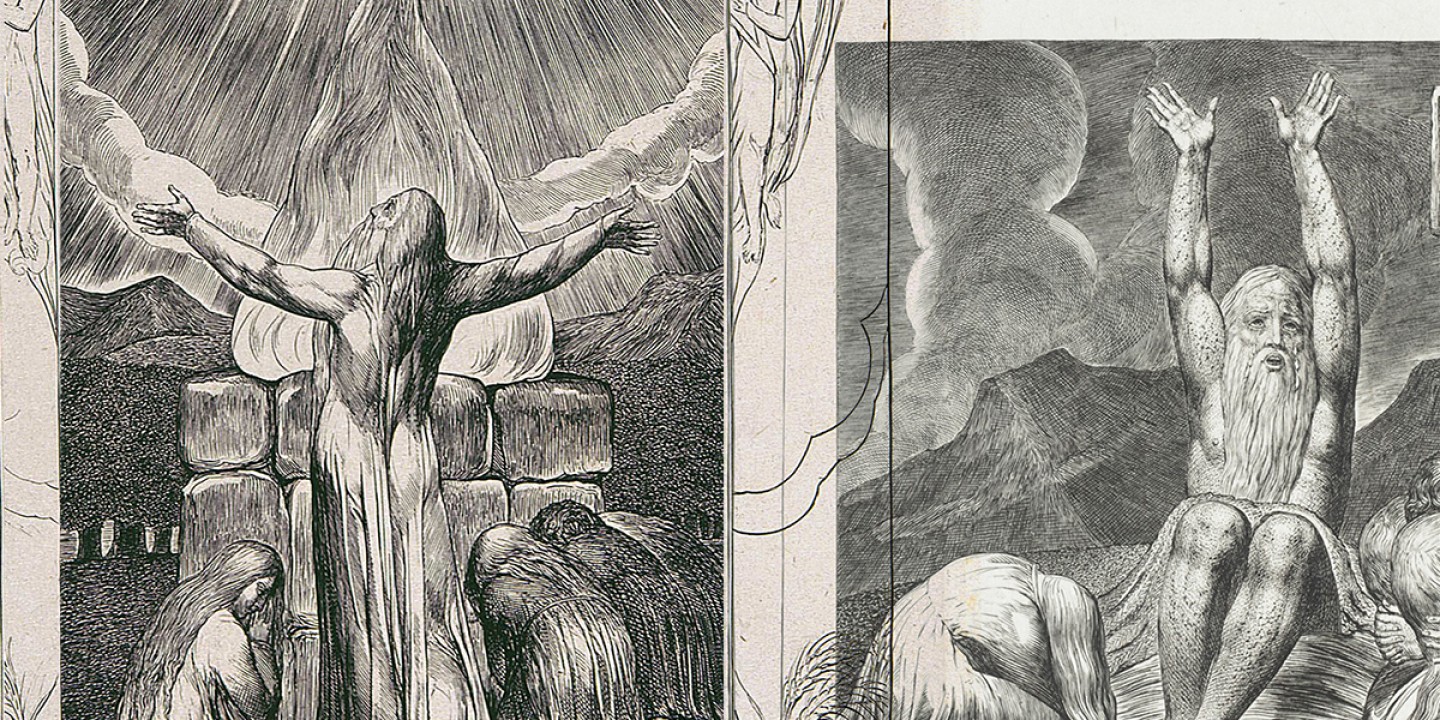

Is the book of Job a tragedy or a comedy? The answer might seem obvious to you. It is perhaps obviously a tragedy: Job suffers both great loss and great physical pain. Lots of people die. Children die. Like almost all tragedies, the book is about suffering and its meaning or lack thereof.

Or maybe it seems obvious that it’s a comedy. The book has a classic comedic shape. Maybe it isn’t exactly funny, but it is placed inside a frame that is simple and even naive, with a happy ending just to be sure we understand that it is a comedy.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

There is a tension between Job’s comedic and tragic elements. Some scholars have dealt with this by noting the lack of unity in the text. They point out that there are deep contradictions between the Job of the prose prologue and epilogue and the Job of the rich poetry in between. Perhaps, they’ve conjectured, the author took a traditional folktale that was widely known by his audience, cracked it open, removed the middle, and inserted his own words. Thus, while interesting, the frame story of the prologue and epilogue has little interpretive value. It may give the book the shape of comedy, but only as an unintended consequence.

I favor a different answer to this comedy versus tragedy dilemma: I believe it lies in properly understanding the frame story. The frame story is not an uncritical retelling of a folktale but rather a highly sophisticated parody of one, written by the author of the poetry. It cannot be discarded like a frame around a painting. Understanding the frame story as parody brings the comic elements in the rest of the book into clearer focus. No, we are not supposed to laugh, but comedy can be a powerful conduit for coping with suffering.

Readers have long wrestled with the contradictory, cruel, possibly insecure God at the center of Job and especially of the frame story. This God is willing to inflict suffering on the innocent because of some cosmic contest? This God plays games with human suffering? Are we supposed to take this God seriously?

The answer—via parody—is both yes and no.

In the frame story, God has a conversation with a character called ha satan. From the very beginning, there is something strange about this conversation. It’s a bit too casual and familiar. God acts very differently in Job compared to other biblical divine council scenes (1 Kings 22, Isa. 6, Zech. 3, Dan. 7). God essentially says, Hey ha satan, what’s up? How ya doing? To which ha satan replies, Ahh, not much, just hangin’.

The very presence of ha satan is telling. The word means adversary or accuser, and an accuser implies an accused. We often assume that Job is the accused, which allows us to blame the figure of ha satan for everything that happens to Job. However, a careful reading of the text clearly indicates that God is the object of the accusation: “Then Satan answered the Lord, ‘Does Job fear God for nothing? Have you [God] not put a fence around him and his house and all that he has, on every side? You have blessed the work of his hands, and his possessions have increased in the land’” (1:9–10).

What is God being accused of? Creating a system in which God essentially bribes people for their piety. Job is not the accused; he is the test case chosen by God because he is innocent. A test, by the way, that Job passes with flying colors.

In the second divine council scene (2:1–6) we find two more disturbing elements indicating the frame story is much more than an innocent folktale. While the second divine council scene repeats much of the language of the first, there is a significant change in 2:3. “The Lord said to Satan, ‘Have you considered my servant Job? There is no one like him on the earth, a blameless and upright man who fears God and turns away from evil. He still persists in his integrity, although you incited me against him, to destroy him for no reason.’”

The idea that anyone, even a divine being, could incite God leaves me speechless, but it doesn’t end there. The text says that God was incited by ha satan to destroy Job “for no reason.” The wording is the same as in the previous scene. Does Job fear God “for nothing,” “for no reason”? Yes, Job does. Does God destroy Job “for nothing,” “for no reason”? Yes, God does. Who then is the figure of greater integrity? It is Job.

Then, even though God has stated clearly that the test of Job was for no reason, at ha satan’s prodding God agrees to test Job again. This is entirely capricious and seriously disturbing. The second test is authorized when God responds to ha satan, “Very well, he is in your power; only spare his life” (2:6). The word translated as “power” is better understood as “watchcare,” a noun most often associated with God’s watchcare of humanity. Here it sounds seriously like an abdication.

Read carefully, the prologue takes a very dark turn. Its apparent innocence or naïveté is in truth quite toxic. The God of the prologue is not the God of Isaiah 6, who sends Isaiah to beg the people to return and be healed. This is not the God of Daniel 7, who sends visions to Daniel to show God's ultimate power and control over the forces of evil. No one, really, has a god like this. Why worship a capricious, insecure deity who tests humans for no reason?

In turn, is Job’s ready acceptance of his loss to be emulated or regarded with suspicion? Maybe it would be better not to be so “blameless and upright” if being this way means becoming a test subject in God’s defense of Godself.

Wait, God needs to defend God’s character? Yes—according to Job 1. In the prologue we are seeing not the author’s view of God but rather a parody of a view of God found in the author’s religious world. And, we might add, in ours.

Sometimes I picture the author of Job looking down at us and shaking his head. What he meant to mock, we take seriously. The book of Job mocks the hollow piety found in his world and in ours. This is the idea that believers are required to act out a false patience and accept suffering as “God’s will.” This view imagines, falsely, that it is more faithful to suppress the pain of our circumstances than to express legitimate anger. It imagines that hard questions lead to lack of faith and that to question God is to invite destruction. It ends up insisting on conformity that leads to spiritual abuse and deforms the human soul.

This is not the faith that the author of Job wants for us.

If we understand Job as a parody, then we know that the author wants to move beyond the many platitudes about suffering that abound in human society. The book of Job thus addresses two powerfully important issues in the life of a believer. First, in the context of faith, human suffering is at heart a God problem, not a human problem. Job is an exploration of the nature of God written by someone who is not afraid to parody God, or at least human versions of God. He subverts theologically simplistic and harmful views of God that he saw around him. He holds up a mirror as if to say, “Look at yourselves, and look at the God your words create!” The author understands that only when we confront our presuppositions are we able to engage in honest conversation.

Second, the book explores how we as believers can suffer with integrity. Suffering is inevitable; how we live through suffering is our choice. Next time you read Job, pay attention to how many times issues of integrity arise.

Does Job maintain his integrity by refusing to curse God and die, as his wife suggests? Or does he lose his integrity by his passively patient acceptance of everything that happens to him? Does he lose his integrity by refusing to admit his sin, as his friends claim? Or does he maintain his integrity by refusing to submit to a theology that has no room for his lived experience? Is it a sign of a loss of faith if while amid great suffering you wish you had never been born? Hope for death? Yell at God? Question God’s goodness?

Some would consider these responses to be outright sinful. But if you look past the first two chapters, you will find Job does all these things.

The book of Job comes into focus as a parody of flimsy faith and platitudes. Its rich poetry gets richer; its contradictions begin to make sense; its capricious God can be interpreted and not simply feared. The implications of this reading may not be fully clear, but at the very least they allow us to return to the book of Job and be surprised.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “A capricious, insecure God.”