It’s time to end our national love affair with guns

Breaking America’s fetish for lethal weapons

I first learned the word enthralled while studying Shakespeare in high school English. It wasn’t a word I immediately began using. But when a teenage couple in the hallway would squeeze in some sensuous kissing time before the bell rang, I knew what it meant. Mr. Taylor would step out of our math class to tell the couple to “quit exchanging spit, and get to class.” Then he’d physically yank them apart. The couple was enthralled with being in love—so absorbed in, mesmerized by, and infatuated with one another that each seemed to have a sort of mystical hold on the other. Such is the enchantment of being enthralled.

Only once have I seen or heard the word disenthralled in use. It’s in Abraham Lincoln’s annual message to Congress from December 1, 1862. Delivered exactly one month before the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, the speech closes with several paragraphs designed to push Americans to rethink their views on slavery. Lincoln offered a glimpse of what was in his own heart:

We can succeed only by concert. It is not, “Can any of us imagine better?” but, “Can we all do better?” . . . The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country. . . . We know how to save the Union. . . . We, even we here, hold the power and bear the responsibility.

Lincoln was positioning the Congress to shift its understanding of the war to be about more than preserving the Union. It now included the aim of ending slavery. With public opinion in the background, Lincoln wanted to do more than imagine a new America. He viewed the whole nation as capable of rising to the occasion of breaking its hypnotic attachment to ideas once considered acceptable. Partly as a strategy to win the war and partly as a way of reckoning with his own evolving position on slavery, Lincoln sought a radical awakening from the status quo. We must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country. In Lincoln’s estimation, the nation needed to break free of its enchantment with ideas about the institution of slavery that were no longer relevant and never deserved to be true.

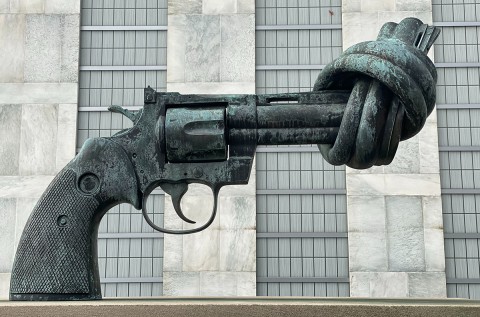

What is there today that we need to disenthrall ourselves of? I can’t help but think of our national love affair with guns. America’s fetish for lethal weapons is well established. The idolatry is all but complete. Liturgies of devotion reverberate after every mass shooting. The gun lobby promotes what Marilynne Robinson calls “a recipe for a completely deranged society . . . [one where] we should all go around capable of a lethal act at any moment.” And although legislators hold the power and bear the responsibility for enacting laws of common sense (e.g., laws to limit access to rapid-fire assault rifles explicitly designed to hunt humans, not animals), many lack the moral courage or conscience to do so.

When a right becomes an acute threat to societal health and well-being, the time would seem ripe for some reevaluation. But first we must disenthrall ourselves—only then might we save our country.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Becoming disenthralled.”