Pauli Murray’s song of hope

Her contributions to this nation can hardly be overstated. The federal government’s attempt to erase them has theological implications.

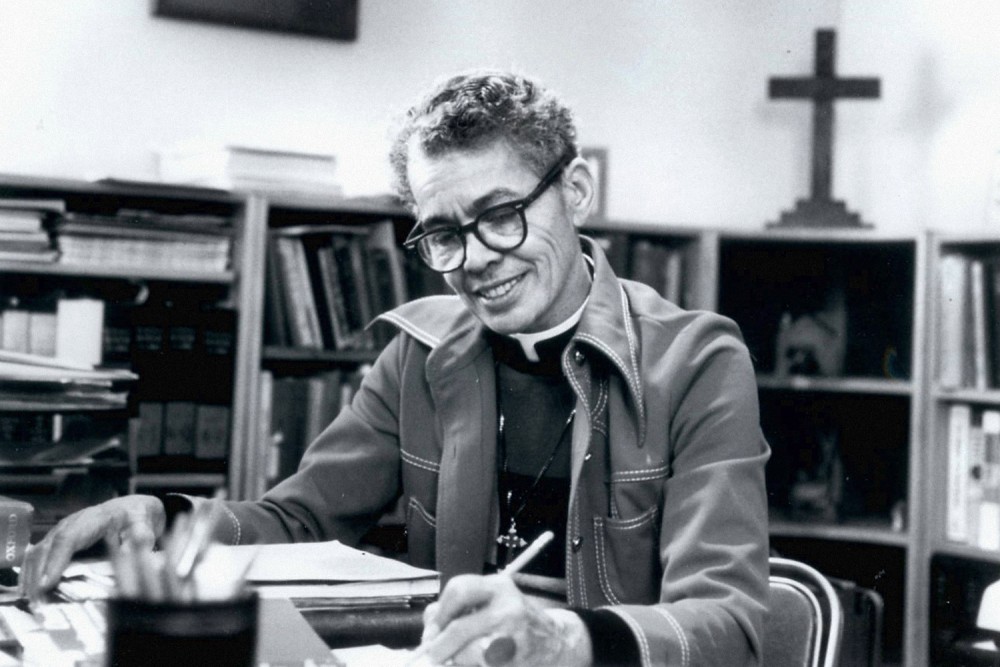

Pauli Murray (University of North Carolina Digital Library and Archives / Wikimedia Commons)

In verse 8 of her lengthy poem “Dark Testament,” Pauli Murray captures the essence of a hope that refuses to be silenced, a hope that persists even in the face of adversity:

Hope is a song in a weary throat.

Give me a song of hope

And a world where I can sing it.

Give me a song of faith

And a people to believe in it.

Give me a song of kindliness

And a country where I can live it.

Give me a song of hope and love

And a brown girl’s heart to hear it.

These lines stand in stark contrast to the Trump administration’s executive order to “restore biological truth” to the United States government—a mandate that seeks to define gender identity in strictly binary terms, erasing from federal resources the lived realities of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming individuals. This action has culminated in the removal of key materials acknowledging their existence, including a National Park Service web page about Murray’s life.

I feel this erasure deeply. As an Episcopal priest serving in the Washington National Cathedral—where Murray became the first Black woman ordained to the priesthood—I am acutely aware of standing on her shoulders. Her life and work, from her groundbreaking role as a civil rights activist and lawyer to her pioneering efforts in gender equality, were fueled by a vision of a truly inclusive society. Yet her contributions, like the song of hope she sang, are threatened by an attempt to exclude the very people she fought for.

Murray’s contributions to this nation can hardly be overstated. Her personal journey exemplifies the complexity of human identity. As a Black woman with multiple racial and gender identities—Black, White, Native American, queer—Murray defied binary categories. Her identity as what she called a “boy-girl”—her refusal to accept the binary gender distinctions imposed by society—was about more than a personal affirmation. It was, at its core, a profound theological conviction that spoke to a larger vision of humanity.

Murray’s theology was rooted in a vision of community that embraced the full diversity of God’s creation, a vision that mirrors the relational and inclusive nature of the Trinitarian God. In this theological framework, the divine unity is not about denying difference but rather about celebrating it. The very essence of God, as understood through the Trinity, points to a reality where diversity and unity coexist in mutuality, equality, and reciprocity. This is a God in whom distinctions are respected and affirmed as part of a larger, interrelated whole.

It is in this way that Murray’s struggle for justice was, as Murray herself came to realize, a spiritual quest. It was a call for the nation to recognize the full spectrum of God’s creation—a call that resonates now more than ever.

By narrowing the scope of gender identity and erasing nonbinary and transgender experiences, the government is not just rejecting the rights of marginalized communities. It is also denying a fundamental truth of the Divine: that God’s creation is inherently diverse and multifaceted, expanding beyond all human binaries of understanding.

As an Episcopal priest and theologian, I am compelled to speak to the spiritual implications of this moment. The deliberate attempt to erase people who do not fit within binary categories is a betrayal of the gospel’s call to honor the dignity of every human being, created in God’s image. The removal of Murray’s web page is not only a political or cultural issue—it is a theological one. An erasure of her vision of a more inclusive and just society is also a denial of the richness and diversity of God’s creation. Murray’s words ring true: “When my brothers try to draw a circle to exclude me, I shall draw a larger circle to include them.” This is the challenge we face today: to draw that larger circle, to honor God’s diverse creation, and to resist any attempt to reduce human identity to narrow, exclusionary categories.

As we stand at this crossroads, it is our responsibility to continue the work that Pauli Murray began: to create a world where all people—regardless of gender identity or race—can live and thrive, where hope can be a song heard by all. We must fight for a world where the Pauli Murrays are not erased but can fully live and move and have their being. Be it through protest with our actions or with our typewriters, as Murray would say, we are called to be nothing less than a song of hope.