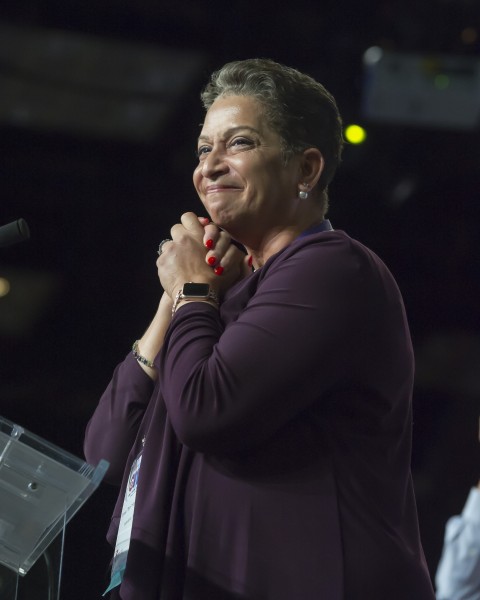

Disciples of Christ elect first woman of color to lead a mainline denomination

Teresa Hord Owens, a descendant of one of Indiana’s oldest free black settlements, is general minister and president.

Despite all the talk of mainline decline, Teresa Hord Owens, the first woman of color to be the top executive of a mainline denomination, is not in survival mode.

“The life that we will find is continuing to be relevant to a society that deeply needs to see hope,” she said.

The Indianapolis-based Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) elected Owens, a descendant of one of Indiana’s oldest free settlements of African Americans, as its general minister and president on July 9.

The denomination, which has 600,000 members in the United States and Canada, has been led for 12 years by Sharon Watkins, who at her election in 2005 was the first woman to be top executive of a mainline body.

Sitting in her office as dean of students at the University of Chicago Divinity School, Owens, 57, who is also senior minister of First Christian Church of Downers Grove, Illinois, looked ahead to her six-year term.

Her particular role is to lead people in efforts where they can agree, especially given the Christian Church’s history of making room for “widely divergent viewpoints concerning ‘nonessentials,’” as denominational literature puts it.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The Disciples have had conflict over LGBTQ inclusion, though a previous General Assembly passed a resolution in favor of it. She noted that the calls she has received have not been about her views on Black Lives Matter, but about sexuality and politics. She emphasized that her desire is to care for the vulnerable, not to align theology and politics.

“We’re disciples of Christ, not of any particular ideology,” she said. Further, since denominational polity lacks emphasis on doctrinal orthodoxy and places high value on congregational discernment, “we have no hammer to lay down.”

She noted that her congregation displays banners with the motto, “In essentials unity, in nonessentials liberty, in all things love.” Unity, she clarifies, isn’t consensus, including in scriptural interpretation. Owens stressed the importance of biblical literacy: wrestling with the text in the pews as well as the pulpit.

“The church really does have to be able to hold all those things in tension and be able to take a stand when it needs to, and keep calling people to account on that issue of love—that cuts through a lot of disagreements about what’s essential and nonessential,” she said. “Unity is not possible if love isn’t right up there with it.”

The assembly theme “One,” based on John 17, “is not calling us to some kind of kumbaya moment.” Rather, she hopes that the Disciples can witness to the world about the gospel of Christ while navigating differences and taking responsibility for the way one person’s positions can harm others.

“Our desire to be right can keep us from being faithful to the ministry we say we’re all called to,” she said.

Before becoming a pastor in her early forties, she worked in the corporate world, including as an informational technology consultant. That background, as well as experience as a university administrator, helps her to see the dynamics of how people work together, which complements seminary training.

“My professional experience has been to walk in, do a lot of listening,” she said, “thinking about where the organization says it wants to be.”

She also looks forward to mentoring future leaders as she builds on the work Watkins did.

“Sharon has wanted to be sure that the church is not bound by its existing structures, to free it up to really do mission,” Owens said.

Watkins has also increased the Disciples ecumenical involvement, which Owens plans to continue, especially collaborating on issues such as racism and health care.

Watkins, 63, currently serves as chair of the board of the National Council of Churches. She has brought to that role her experience in discerning which parts of church tradition are crucial and which parts may be left behind.

“The call for ecumenical Christians is to share that gospel in a way that’s meaningful, and to not be weighed down by the things that are beloved but not useful for mission in this time,” she said. “We’re living in a time now when our neighbors don’t know that God is a god of love, that we are called to be people of love, to work for the common good, to work for justice.”

Part of her focus with the Disciples was “working hard on being a pro-reconciling, antiracist church,” an effort that will continue.

It included an audit of the denomination’s governance documents for racist language. Officials learned that words or phrasing don’t have to be clearly hateful to reflect an unconscious superiority or dependence on one cultural perspective.

Working on such awareness in a denominational setting reaches some people who wouldn’t have encountered it.

“We’ve been able to push that antiracism work deeper in the church and reach some people who otherwise wouldn’t have raised their hands to volunteer,” she said.

Being the first woman to be top executive of a mainline denomination was “mostly advantage,” Watkins said.

“My speaking up interrupted the flow, not in a bad way, but just for a beat, for people to look at how they were doing things,” she said.

Watkins was the first woman to be selected to preach at the National Prayer Service in Washington, D.C., the day after a presidential inauguration, having been invited by President Barack Obama. She later served a term on President Obama’s Advisory Council on Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships.

While Watkins takes a sabbatical and discerns her next ministry position, she’s pleased to pass her role with the Disciples on to another woman, saying, “I’m glad that the first time around didn’t make us think we couldn’t do it again.”

A version of this article, which was edited on July 14, appears in the August 2 print edition under the title “People: Teresa Hord Owens and Sharon Watkins.”