Century Marks

Through a glass: Selling off assets to make ends meet is not new for churches. But two separate congregations planning to sell their Tiffany windows caught the attention of national media. St. John’s Episcopal in Elizabeth, New Jersey, agreed to sell three Tiffany windows to a collector, and the First Baptist Church in Brattleboro, Vermont, agreed to seek bids for its nearly 100-year-old window picturing St. John the Divine. First Baptist planned to sell the window to continue funding a much-in-demand homeless shelter in their church. “This Tiffany window—as beautiful as it is—is [just] a material thing,” said the pastor at First Baptist. After First Baptist’s story aired on ABC News, pledges came in that appear to have saved the window for the congregation (AP).

Up with religion: Religion is now the most popular theme studied by historians, according to a member survey by the American Historical Association. Culture had previously taken the top spot in surveys over the past 15 years. Explanations for this interest in religion are the increase in activist and, in some cases, militant religion, the failure of the secularization theory in the light of an upsurge in religion and increased student demand for courses in religion. The new interest, pronounced among junior scholars, is likely to increase. A decade ago only 2 percent of job openings and fellowships posted with the AHA listed religion among the desired specializations; last year, 10 percent listed religion (Inside Higher Ed, December 21).

God on the brain: Researchers asked both believers and nonbelievers to ponder God as savior, forgiver and moral guide while having their brains scanned. The scans revealed that particular neural paths were engaged, including those in the anterior prefrontal cortex. This is also the area of the brain where empathy for others is lodged; and it is the part of the brain most recently developed and is much larger in humans than in apes. The anterior prefrontal cortex gives humans the capacity to explain mysterious phenomena and to bring groups of people together (Discover, January/February).

What’s a prophet to do? We’re inclined to believe prophets are heroic individuals, lonely figures who stand up against the powers that be. But the late James Luther Adams, Unitarian theologian at Harvard Divinity School, caught the biblical vision of prophecy—that we are all called to the prophethood of believers, just as we are to the priesthood of believers (see Num. 11:24–30; Joel 3:1–2). Old Testament scholar Patrick D. Miller thinks Adams was also correct to suggest that the role of a prophet was not just to forthtell, but also to foretell; to be a prophet means having the ability “to interpret the signs of the times and to see into the future,” as Adams put it. “Hope is a virtue,” said Adams, “but only when it is accompanied by prediction and by the daring of new decisions, only where the prophethood of all believers creates epochal thinking” (Theology Today, January).

Bottom line: In opinion polls Americans agree they want full medical insurance coverage at lower cost, longer life expectancy, less crime and better public services. However, if told they could have all this in Austria, Scandinavia or the Netherlands and it would come at a cost—higher taxes and greater state intervention—they demur. “We don’t want socialism” is a typical American response. Tony Judt discerns something deeper than the American resistance to government programs and intervention: a propensity to avoid moral considerations and a prejudice for asking economic questions: “Is it efficient? Is it productive? Would it benefit gross domestic product? Will it contribute to growth?” (New York Review of Books, December 17).

O little town: It once took just 15 minutes to get from Bethlehem to Jerusalem, but now for Palestinians it can take hours to get through security check points. Said one university student, “Jesus Christ wouldn’t be able to leave Bethlehem today unless he showed a magnetic ID card, a permit, and his thumbprint.” The 26-foot-high security wall built by Israel seals off Bethlehem from three sides and has devastated the economy of the city where Jesus was born. About 50 restaurants, 28 hotels and 240 souvenir shops have closed in the last seven years due to a sharp drop in tourism. While tourism has improved since 2008, unemployment still hovers around 20 percent, and Christians are emigrating elsewhere. The Christian population of Bethlehem was 92 percent in 1948, but now has dipped well below 50 percent (The Week, December 25–January 8).

On a hill far away: For over 450 years the Vatican has been trying to win back control of the Holy Cenacle, the place on Mount Zion where Jesus supposedly gathered with his disciples for the Last Supper. The Franciscans maintained the cite prior to 1551, when it was seized by the Ottoman Empire. Now the Vatican and the Israeli government are locked in a dispute over its disposition. A spokesperson for Israel said he hopes a compromise can be reached, but the Vatican can’t expect to get total sovereignty. Like so much else in Jerusalem, the disputed spot has multiple associations: it sits on top of the Tomb of David where some Jews believe King David was buried; and during the Ottoman period it functioned as a mosque (Chicago Tribune, December 24).

Retirement plan: Due to aging populations and declining birth rates, Western industrialized countries will need immigrants in order to keep their economies running. Countries that do the best job of assimilating immigrants will be the most successful. But another kind of immigration should be considered—reverse immigration, in which the elderly move from developed to developing countries in their retirement. Developing countries would benefit, because providing leisure and retirement services is labor intensive; and the developed countries would see a reduction in the cost of entitlement services (Foreign Affairs, January/February).

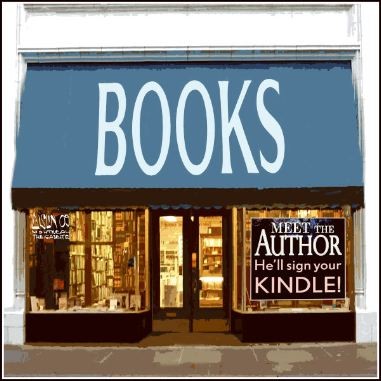

Where are the women? None of the authors of Publishers Weekly’s top ten books for 2009 were women, and only 29 women were among the authors in the list of top 100 books. This result tracks pretty closely with the Pulitzer Prize: in the past 30 years only 11 awards have gone to women. And in Amazon’s top 100 books for 2009 only two women made the top ten and four the top 20. Julianna Baggott notes that, for an industry kept afloat by women, these skewed figures seem sexist (Washington Post, December 30).