The Trump administration hasn’t attacked religious schools and seminaries—yet

Liberation theologian Ignacio Ellacuría didn’t leave us a blueprint for resistance, but he speaks to times like ours.

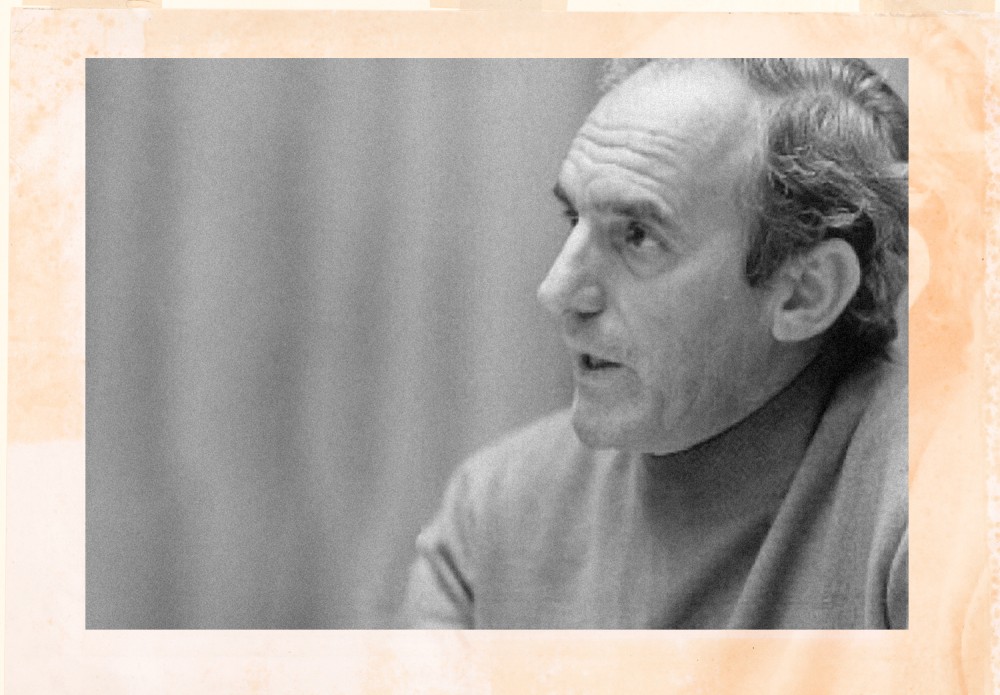

Theologian Ignacio Ellacuría in 1989 (Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

In November 2016, I was a freshman at a private Christian liberal arts college, where the other students were mostly White, mostly middle class, and mostly evangelical. When Donald Trump was elected for his first term as president, some of us were disheartened. Others were delighted. I was anxious. For me, Trump’s first election felt like the electoral consequence of the festering racism I’d witnessed throughout my adolescent years, including the brutal police killings of African American boys and the normalization of overt, anti-immigrant hostility.

A few months before the election I grabbed coffee with a friend who worked for the college. He took me to a cute bakery in a bustling suburban downtown strip. He listened to my anxieties: Why would Christians consider voting for Trump? How could they be so indifferent to racism? Why do I feel like I don’t belong in this school—and like I’m asking different questions from my peers, shaped as they are by my family’s Filipino, Mexican, and American context?

My friend listened patiently before asking if I’d heard of theologian James Cone or his book God of the Oppressed. When I used what little money I had to buy a copy, I devoured it. I read it at lunch. I read it in the evening. Between my readings for other courses, I made the book a priority. I had few friends then, and Cone became one of them.

Today, the annotations in my now-worn copy make little sense. But they do reveal a mind coming into itself, and an imagination opened wide by the horizon of radically new ideas. The next semester I took a systematic theology class, and God of the Oppressed was assigned as the main text. We discussed Cone’s critique of the White social context shaping North American theology. We discussed Cone’s daring assertion that God wills liberation, as Exodus and the Prophets and the New Testament suggest. We worked through Cone’s conclusion that Jesus is Black, because Jesus identifies himself with those on the margins, which in North America are those who have suffered under the weight of anti-Black racism, chattel slavery, the war on drugs, and mass incarceration.

Cone helped me to see that the language of God cannot be separated from the social context in which it is invoked and put into practice. He, alongside the teachers who encouraged me to read him, helped me trace the connection between Trump’s courting of the evangelical mind and the legacy upon which Trump and his followers stand.

More than that, Cone set the trajectory for the rest of my college education. I took courses on colonialism, Christian ethics, Critical Race Theory, the Haitian Revolution, theology, urban studies, and race. My teachers encouraged me to be a student who traversed theology, philosophy, and social theory with an eye to how a Christian life of the mind cultivates social responsibility amid the political issues that manifest in that life—from racism to gender inequalities to still-entrenched class and race-based segregation. When I graduated, I decided to pursue graduate work in theology and ethics and continue my study of race, religion, and liberation theology.

But I fear the kind of education I had is now being undermined with a force not seen in decades. The Trump administration’s anti-DEI policies and threats to university funding have discouraged the kinds of race-conscious, historically robust, socially-attuned education I received eight years ago. International students and professors have had their visas revoked; some have fled the country, and others have been forcibly detained and disappeared. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has threatened more student visa terminations on the grounds that foreign students hold university campuses “hostage.” Columbia University at first capitulated to Trump’s request. Now we are seeing other institutions, including Harvard and Rutgers, refuse to do so.

The political upending of higher education inevitably raises the question: What, exactly, are colleges and universities for? What is the relationship of higher ed to politics, to the material needs and concerns of their students, and also to the public? Religious colleges and seminaries in the U.S. must also attend to these questions, even if they have not yet been the direct target of Trump’s educational agenda.

This is not the first time these questions have been asked. In 1982, Ignacio Ellacuría, the Spanish Salvadoran liberation theologian and president of the University of Central America (UCA) in El Salvador, delivered a speech at the University of Santa Clara titled “The Task of the Christian University.” The speech was based on the work of the UCA, which had been a powerful educational force in El Salvador, reporting on political corruption in the government and, years later, becoming a beacon for peace talks to end the country’s civil war. In 1989, Ellacuría was murdered by soldiers in the Salvadoran military for his decidedly political stance.

In his speech, Ellacuría calls for a Christian university to be accountable to “social reality.” The university is a “social force,” he says, representing the constituencies of which it is part and from which its students and faculty come. While its primary call may be to cultivate intellectual virtues, it cannot do so abstracted from how such virtues are used in society. “It must transform and enlighten the society in which it lives,” says Ellacuría.

For Ellacuría, the Christian university is marked by a further commitment to liberation from unjust material conditions. Here, the liberationist impulse of his theology shapes his wider vision for education:

“Liberation theology has emphasized what the preferential option for the poor means in authentic Christianity. Such an option constitutes an essential part of Christian life—and also a historic obligation. … Reason and faith merge, therefore, in confronting the reality of the poor. Reason must open its eyes to the fact of suffering.”

Ultimately, he calls for a “university for the people,” though he says we will have to imagine what that looks like for ourselves. In the U.S., this aspiration ought to go far beyond reading liberation theology and adjusting classroom curriculum.

Imagine a seminary that encourages dissent on theological grounds; that has research centers actively documenting local economic, social, and political needs, nationwide and global abuses by the U.S. itself; that protects international students from disappearances; that protests and denounces in its immediate community unjust government overreach through documenting, reporting, and petitioning such violations. A seminary for the people would imagine its work, and the cultivation of its students’ scholarly and pastoral vocations, in terms of what it owes to the public in which it is situated. Where such a public is under vicious forms of dehumanizing repression, such as coercive and undemocratic educational reform, arbitrary deportations, and the squashing of student dissent, this seminary would take an active stance against the forces of such repression.

At the end of his speech, Ellacuría recognizes the risks entailed in such a social vision of the university. UCA, he says, has been bombed, raided, “and threatened with the termination of all financial aid.” He knew something of the experience many in our communities are now facing: “Dozens of students and teachers have had to flee the country in exile; a student was shot to death by police who entered the campus.” But this cannot detract from what is called forth from a Christian vision of the university.

While Ellacuría may not provide a blueprint specific to the needs of our time, he unapologetically uplifts the values around which Christian universities should be committed, especially in socially vulnerable times like ours. He does not call for a partisan university, though it is a politicized university accountable to transforming society, a conviction rooted in an understanding of God as the one who brings liberation.

Of course, this conviction is not unique to liberation theology alone. Truth, in the Gospel of John, is not abstracted from the one who is truth, Jesus of Nazareth, who proclaims the reign of God in an imperial territory of the Roman empire. In De Trinitate, Augustine makes Truth accountable to a robust vision of the love of neighbor: “… for the cause of his not seeing God is that he does not love his brother.” Real though our vulnerabilities may be, we students, seminarians, pastors, and professors cannot forego the prophetic element required of Christian education.

Today, as I page through my copy of God of the Oppressed, now nearly eight years old, I am one year into a PhD in theology, and still, Cone’s insight feels urgent:

“For theologians to speak of … God, they too must become interested in politics and economics, recognizing that there is no truth about Yahweh unless it is the truth of freedom as the event is revealed in the oppressed people’s struggle for justice in the world.”

Ellacuría’s vision of the university speaks directly to this observation. And if Christian institutions of higher education are to remain Christian amid Trump’s repressive educational policies, it is this truth to which they are utterly accountable.