Fashion-forward faith

Muslim women’s clothing reveals—and shapes—culture, politics, and piety.

I attended graduate school with Elizabeth Bucar, and I didn’t know her well but I’ve always remembered two things about her: she was a sharp thinker, and she dressed with flair. I’m no fashionista, so the fact that I can recall anything about a fellow student’s clothing 20 years later leads me to believe that the level of Bucar’s flair must have been extensive. (Then again, any such claim should be relativized by the fact that we studied at an institution that prides itself on being a place where students live “from the neck up.”)

Non-Muslims generally describe Muslim women’s clothing from the neck up as well. We tend to focus on the hijab and what it indicates about assimilation, Islam, and the relationships between men and women. The brilliance of Bucar’s book is that she goes beyond the hijab, showing how seamlessly (pun unintended) an entire outfit can carry multiple resonances, simultaneously revealing truths about piety, the body, gender, and politics. She shows how women’s sartorial choices within Islamic norms—and their interpretations of those choices—reflect and shape the values of a faith tradition, create spaces for agency and judgment, indicate or obscure economic status, secure or foreclose access to political power, and allow for individual expression.

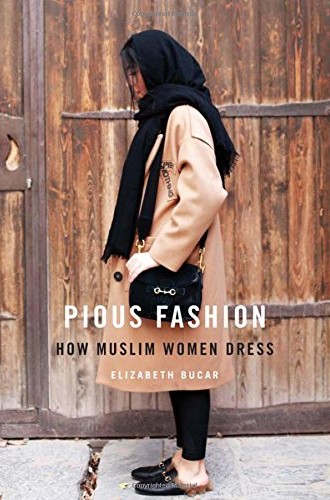

Bucar analyzes the clothing worn by young Muslim women in Tehran, Iran; Yogyakarta, Indonesia; and Istanbul, Turkey. She blends history, anthropology, personal experience, interviews, and stunning photographs from fashion blogs to present a vivid cross-cultural picture of the complex relationship between clothing, faith, and beauty.

The diversity in Bucar’s rich descriptions of fashionable clothing styles might be expected in a book of this nature. But just as diverse are the “fashion failures” noted by the young women she interviews:

When women identify another woman’s clothing as a fashion failure, they are also expressing ambivalence about their own personal sartorial practice and others’ monitoring of it. Pious fashion creates aesthetic and moral anxiety. Am I doing it right? Do I look modest? Professional? Stylish? Feminine? Women try to resolve this anxiety by identifying who is doing it wrong. Judging certain styles as failures of pious fashion can thus be interpreted as the expression of internalized anxieties regarding law-breaking (in Tehran), ugliness (in Tehran and Istanbul), vulgarity (in Yogyakarta and Istanbul), and deception (in Yogyakarta and Istanbul).

This sort of second-order reflection—an analysis of women judging other women’s clothing—is balanced by the tangible descriptions and pictures of clothing that make up the bulk of the book. Bucar spends an entire page describing the clothing of a woman who she observed at a tourist site in Turkey, summarizing the look of the overcoat with these words: “It was a sophisticated mashup of trends: the cut was soft, feminine, and retro, but the trimmings were edgy, modern, masculine, and fashion-forward.”

The ethical ambiguities of writing a book about women’s fashion (which risks participating in the sort of “gendered scrutiny” that “reinforces the notion that a woman’s appearance is a significant marker of her agency, competency, and identity”) are not lost on Bucar. But, she explains, “how we experience dress depends on how others evaluate it, so scrutiny is a necessary part of my ethnographic method.” I would make the case that all ethnographers could be accused of objectifying the people they study—and, even more broadly, that such a task is at the heart of the academic enterprise. Scholars turn people, philosophies, histories, and texts into objects of scrutiny. Still, I’ll admit that before reading the book I felt some discomfort with the idea that I would be evaluating women’s clothing.

My worries were alleviated by two characteristics of the book. First, Bucar, as a woman traveling in Muslim-majority countries, participates in the sartorial practices she evaluates. She scrutinizes herself as well as the young women who participated in her interviews and focus groups. Second, the photographs in the book come from fashion blogs. While they visually exemplify the kinds of trends and styles Bucar analyzes, the textual analysis doesn’t scrutinize the photos. This disjunction makes for a somewhat choppy reading experience, but it also means that the women in the reader’s gaze are only those who have agreed to have their photographs widely disseminated and discussed through the lens of fashion.

If anything, Bucar’s book has helped me gaze more generously upon the piously-dressed Muslim women who I encounter in my daily life. I find now that I’m less likely to view them flatly as participant-victims in an oppressive patriarchal system and more likely to view them as individuals whose agency, particularity, and beauty are reflected in their clothing.