For better or for worse, the church is keeping Haiti afloat

In the absence of strong political leadership, someone has to fill the void.

When societies lack good governance and social stability, churches and clergy often fill in the gaps. In some cases, notably in modern Africa, church leaders can become something like kingmakers. In the Western Hemisphere, the nation of Haiti exemplifies the pivotal role of Christian churches in politics.

The nation was born in the 1790s from the incredible turmoil of the great revolt of an enslaved population and the decades of war and devastation that followed. Famously, Haiti has always retained its African religious heritage in the form of vodun, but the great majority of the people also asserted their faithful Catholic roots. Most recently, evangelical and Pentecostal churches have boomed, partly as a consequence of the new forms of faith Haitian migrants encountered when they set up homes in US cities such as Boston and Miami. Today, Protestants (mainly evangelicals) make up some 30 percent of the country’s 11 million people, compared to 55 percent Catholic and 10 percent nones.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

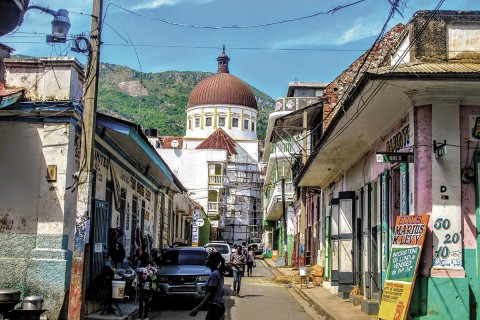

Haiti’s modern history has witnessed many disasters, both human-driven and natural. From 1957 through 1986, the country was ruled with appalling tyranny by the Duvalier family, and more recent regimes have often been deeply unstable. The results of the 2015 election were so controversial that they were eventually annulled, as extensive popular protests and demonstrations became an endemic fact of life. Last year, Haitian president Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in still unexplained circumstances. The country is by far the poorest in the Western Hemisphere, with 60 percent of Haitians living below the poverty line; it is also marked by extreme wealth inequality. As if these horrors were not enough, a 2010 earthquake killed 300,000 and devastated the capital, Port-au-Prince.

Church leaders have often been called on to intervene in what seems like a situation of endless chaos. The Catholic Church in Haiti has changed dramatically in recent decades. Prior to the 1950s, the Catholic clergy were mostly White and European, and they regarded the struggle against religious syncretism as a primary task. Only in the Duvalier years, with the spread of ideas of liberation theology, did the church place social justice at the heart of its agenda. To the church’s great credit, François Duvalier—”Papa Doc”—loathed the institution and its clergy, and the church in turn excommunicated him. During the 1970s, the church became much more accommodating to African traditions, including the Creole language. That church role was particularly crucial because the Duvaliers had all but extinguished most other forms of civil society. One key symbolic moment in church attitudes occurred in 1983, during a visit by Pope John Paul II, who famously proclaimed, “Things must change here!” After the fall of the dictatorship, the church struggled to defend the new democratic constitution.

The prestige that the church earned in these struggles was reflected in the political triumph of a Catholic priest noted for his work with slum dwellers, the Salesian father Jean-Bertrand Aristide. In various ways, Aristide’s career became the unavoidable centerpiece of Haitian history from 1990 onward, and his influence is by no means extinct.

Aristide became the focus of a swelling populist movement, and that political role—with its apparent threat of insurgency—profoundly discomfited his Salesian order. He finally left the priesthood in 1994, but all his actions must be understood through the lens of liberation theology—for better and for worse.

In 1991, Aristide became the country’s first ever democratically elected president, winning 67 percent of the vote. Facing almost incredible odds, he scored some real achievements, improving education and health care and dismantling some of the country’s most notorious paramilitary death squads. Sadly, Aristide’s rule disappointed hopes of a new democratic consensus, leading as it did to extensive plots and coup attempts by rightist and military groups, along with popular protests against misgovernance. His government was accused of its own human rights abuses and violence against opponents, though on a far lesser scale than earlier regimes. Forced into African exile in 2004, he returned to Haiti only in 2011.

Aristide left a mixed legacy for subsequent Catholic leaders, who recognize the church’s central role in creating stability and reducing poverty. Repeatedly, during times of violence and political chaos, it is the bishops who have been called on to mediate and to encourage free elections. At the same time, Aristide’s turbulent record raised real concerns.

In 2014, Haiti received its first ever cardinal in the person of Chibly Langlois, the bishop of the small diocese of Les Cayes. The appointment surprised many because the new cardinal was well known for his quiet and conciliatory style, which might not be sufficient to the desperate circumstances in which the country now stands. What is not in question is that the church is crucial for the nation’s well-being, and perhaps its survival. If not the church, who?

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Filling the void in Haiti.”