It’s difficult to feel sorry for people who get to spend their workday at baseball games. Even so, it’s hard not to feel at least a little bit of sympathy for umpires. As the old saying goes, umpires are supposed to be perfect from day one and get better from there. Any failure to achieve perfection is met with calls of derision. Hey, ump, are you blind? How did you not see that?

As a lifelong fan of the Kansas City Royals, I’ll never forget the first-base umpire blowing a call late in game six of the 1985 World Series. (The call hurt the other team, the St. Louis Cardinals, so I for one found it easy to forgive.) Even people with perfectly good eyesight sometimes fail to see things that are right in front of them.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

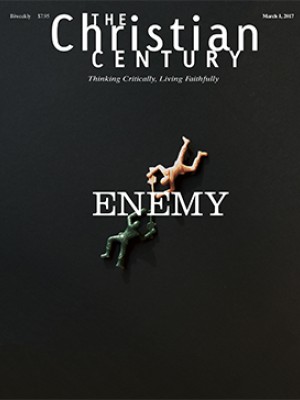

The contrast between sight and blindness is at the heart of the extended scene that plays out in John 9. It is the story of an unnamed man born blind who regains his sight, told in contrast to those who were born with sight and yet are unable to see what is right in front of them.

The sign at the beginning of the chapter seems straightforward enough, albeit miraculous. Jesus and his disciples encounter the blind man. The disciples want to turn the man’s existence into a theology class, a consideration of whose sin caused the blindness. Jesus isn’t interested. He sees instead an opportunity to show forth the power of God. In short, he heals the man.

John’s readers would not be faulted for assuming that joyful celebration would ensue. Instead, we get a tragicomedy populated by people who simply refuse to acknowledge what they can plainly see with their own perfectly functional eyes.

It begins with the neighbors, who have a hard time seeing that this man is the same man who was once blind, even though nothing else about his appearance has changed. Next it’s the Pharisees, blinded by their rigid interpretation of the law. Jesus heals the man on the Sabbath, and no righteous person would do that; therefore some of them insist that Jesus must be a sinner, not a healer. In spite of the walking, talking evidence in front of them, they are blind to God’s power at work in their midst.

The man’s own parents, blinded by fear of the Pharisees, fail to see that God is doing a new thing that transcends the authority of the Pharisees and even the law itself. Neighbors, Pharisees, parents—they all can see that Jesus has restored the blind man’s sight, and they all fail to see it for what it is. They are all blind in one way or another to Jesus, the light of the world.

It is only the man who was once physically blind who can see Jesus for who he is, the Son of Man who has come to bring sight and light to this world. Those who can see become blind; those who are blind will see. John uses this sign of power and healing to continue to unfold his great theme of the contrast between light and darkness, upending our false assumptions along the way.

We like to say that seeing is believing. Yet when Jesus clearly demonstrates the compassionate power of God, we look for reasons not to believe. John invites us to see ourselves in the disciples, neighbors, Pharisees, and parents. We are those who prefer not to see what is right in front of our noses, who would prefer to live in the darkness we know rather than open our eyes to the blinding, brilliant light of God’s presence in our midst. Still, the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness does not overcome it.

In the darkness, we have the luxury of having conversations about the sins and sufferings of others without acknowledging our own sin. In the darkness, we are free to pretend that we don’t see the suffering and pain of those around us, that we are not called to respond with love and healing. Jesus, however, has not come to enable us to remain in the dark. Jesus has come to bring sight to the blind, even those who believe they can already see. In the bizarre grace of God, Jesus does not remain at a distance from us. He enters into the muddiness of this world and gets his hands dirty for our sake.

Jesus takes all of the deep darkness and the willful blindness of this world upon himself on the cross, and he does so to open our eyes. This means opening our eyes and our hearts in compassion for those who suffer. But first it means opening our eyes to the presence of Jesus, the Word made flesh, the glory of God shining hard and bright in his death and resurrection. As it was for the man born blind, so it is for us. We stare into the eyes of the Son of Man; we fall down and worship the one who has banished the darkness.

Once we see Jesus, we are no longer free to be blind. Those who worship Christ are called to see what is right in front of our eyes: the hungry, the homeless, the displaced, the terrorized, the marginalized. The people of God no longer have the luxury or the capacity to ignore those in need. We cannot trust our own sight; even the best umpires make the wrong call from time to time. Thankfully, in and through Jesus, we don’t have to trust our eyes. We simply have to trust him as he reveals, over and again, the work that God continues to accomplish right in front of us.