April 19, Good Friday (John 18:1-19:42)

When I say the creeds, Pilate’s name stands as a warning back to myself.

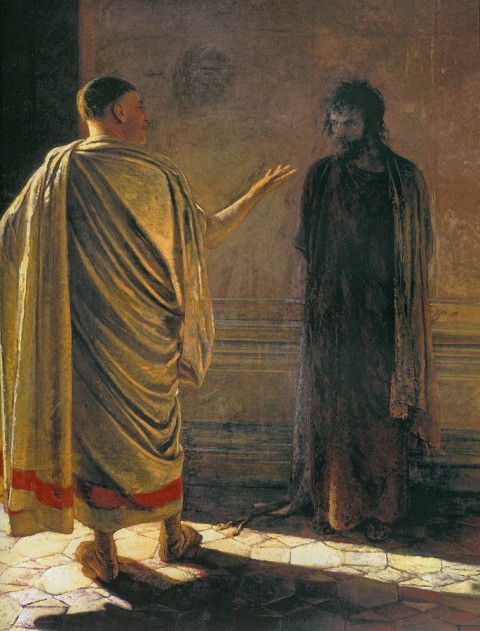

On Good Friday, John 18 invites us to observe an interaction between Pilate, the provincial governor of Judea, and Jesus, an arrestee suspected of whipping up insurrection. As a Roman governor, Pilate was a middle man in the architecture of Pax Romana. His primary job was to exact order from a volatile political landscape, and he had almost complete control over his local jurisdiction—the power of life and death over those he ruled. In the writings of Philo and Josephus, he is described as capricious and cruel.

Yet, in John’s Gospel, Pilate appears subject both to the demands of the religious authorities and to Jesus, who voices enigmatic questions that befuddle this hapless mediator. Pilate’s confusion and bumbling are embodied in his physical movement. He goes back and forth, in and out of the praetorium, out of control over the situation that is unfolding.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Herein lies John’s inversion of power. What we imagine, what Pilate imagines, is that he decides the fate of Jesus. Pilate operates under the incomparable power of Rome. In the scene of Jesus’ trial we begin to see the unraveling of Rome’s grasp on history through coercion and terror. As the story moves on we end up at an empty tomb where we discover that love is stronger than death. Before Pilate, we begin to understand that Rome’s authority is temporal, of human origin; Jesus’ power is eternal, given to him by his Father.

Inside the praetorium, Jesus is held for questioning. The synoptic Gospels end with only a single question fired off by Pilate (“Are you the King of the Jews?”). John gives us the opportunity to see the governor undone by the answers to several questions he sets to Jesus. In this interrogation we see two men operating in two different worlds, in two different kingdoms. Pilate thinks in terms of governance and uprisings, of stifling political threats and bringing minority religions under Roman authority. Jesus comes to tell the truth about the world.

Jesus the messiah is incomprehensible to Pilate. Pilate barks out his famous question, “What is truth?” Without waiting for an answer, he goes back outside to negotiate his way out of this judicial impasse. He offers to release Jesus for the tradition of pardon during Passover. Ironically, the mob gathered outside asks instead for the release of the murderer and political dissident Barabbas. Even more ironically, Pilate grants their request—thus condemning to death one who lived a nonviolent life, who never spoke out against the state, who would not raise a sword against Rome.

It’s a farce, a parade of nonsense and cruelty. But from Rome’s perspective, Jesus cannot be allowed to go on preaching and teaching. More powerful than swords or guerrilla warfare is the possibility that God is on the side of the poor and that God is here among them, that a new world is opening up before them.

Crucifixion enforced order. It was ubiquitous in the ancient world as death by torture reserved for those who incited rebellion. It was a form of social control, bodies on crosses strategically placed at crossroads to remind the people of the power of Rome to crush their dreams of freedom. Be wary, all those who take a stand against the empire.

I’ve heard it said that the cross was the equivalent of a modern-day electric chair. James Cone helped us to see these excruciating and humiliating deaths another way. “Every lynching tree is a cross, and every cross is a lynching tree,” Cone writes in The Cross and the Lynching Tree. It is a form of death that cements a social order of terror in the bodies of oppressed people, a way to fortify within human bodies a world order. Jesus’ death was a lynching.

Pilate reminds me that it takes the passive participation of people like me to put such actions into motion. Just like in the Gospel of John, thousands of people gathered to watch a lynching. The majority of lynchings took place in the Bible Belt, instigated by churchgoing folk who felt the need to be realistic about the potential threat of their former slaves. Whites in the South took this on as a religious mission—bearing witness to the God-given superiority of whites over blacks.

This is what Hannah Arendt called the “banality of evil.” I’m just doing my job. This is just the way it is. Who am I to question my leader or my pastor or my legislator? It’s too risky. Who am I to change things?

When I speak Pilate’s name aloud, as I do often when reciting the creeds, he stands as a warning back to myself, a reminder that evil in its pervasive and haunting form does not look like white hoods or swastikas. Often evil is ordinary and ordered, pulling us into a posture of complacency, our hands thrown up in the air in resignation. Perhaps, we tell ourselves, we need this terror to protect the common good. Perhaps this is what keeps us safe and secure, what keeps people in line.

On the other side of this warning stands Jesus, the one whose life resists the social order propagated by Rome. Throughout John’s Gospel his strangeness opens up people to possibilities they cannot fully understand. Unlike Rome’s strategy of terrorizing control, Jesus embodies a slow, unraveling love. It’s a love that is incomprehensible to powers of domination, a love that gets swept up in cruelty and torture. In the end, it is a love that offers up no resistance when faced with death.