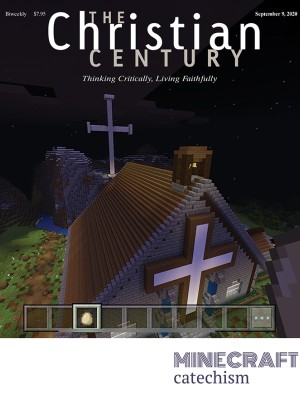

How I used Minecraft with my catechism group

Instead of memorizing Luther’s theology, the kids built churches that embodied it.

With more than 112 million monthly users, Minecraft is the best-selling video game of all time. It’s been wildly popular among young people and adults all over the world since its release in 2009, and it’s now one of the games most widely streamed on Twitch and YouTube channels.

As it turns out, it’s also a great way to explore faith in creative and collaborative ways. I know this because I used it with my catechism group this past school year.

Here’s how it happened. I sat down with our middle schoolers on the first day of Sunday school last fall and asked, “How would you like to learn together?” Someone joked that we should play Minecraft, and I asked, “How would that work?” And then the class began to teach me.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Minecraft is a sandbox game, which means it’s designed for players to be able to create, modify, or destroy their environment. Players can build almost anything in Minecraft: machines, trees, buildings, animals, dungeons, lakes, terrain, weapons, computers, and more.

Over the course of that hour I asked a lot of questions: How can we learn in Minecraft? How will it work to play it in class? What kinds of rules will we need to have? I learned that there’s a way for many Minecraft players to play together in a shared world. We came up with a plan to learn Martin Luther’s Small Catechism while building churches in Minecraft.

I went home and got busy. My first step was to purchase a Realm for the church. Minecraft Realms is a subscription service that allows you to set up invitation-only Minecraft worlds that exist in the cloud (as opposed to being stored on an individual player’s device). Once a Realm is set up, anyone with the correct login can join it, from any device with a Minecraft app. The Realm is stable: each time someone visits it, whatever has been built on previous visits remains in place. And it’s accessible to all members on the cloud, so everyone participates in the building of a world together.

My students and I decided to structure our Minecraft catechism lessons as a church architecture contest. We formed two teams. Each team would plan and build a church that reflected Luther’s theology. The church building would happen each week during the Sunday school hour as the students learned about the catechism.

We adopted a set of simple rules to make the game play fair and fun. For example, we made a rule against sabotaging the other team’s church. (That would be akin to kicking down someone’s sandcastle at the beach.) We gave bonus points to features that paid homage to famous churches or to churches with which the children were familiar. And we required that each church include “stations of the catechism,” making the full text of the Small Catechism available to visitors for reading and study.

Not everything was easy to accomplish. The technology presented a few challenges. I had to work with individual children to figure out how each one’s handheld device would connect to the Realm. Some were naturals at this, or their parents were. Others needed more hand-holding. We set up an Xbox with four controllers in the youth room so anyone without access to the Realm from a handheld device could still play in person at church.

It also took a few weeks to establish some shared play habits, not unlike the way kids on the playground have to sort out rules of engagement before they can play the complex game they’ve just invented. My students had to learn different habits for group play than they were used to employing when playing the game alone.

Still, they quickly latched onto Minecraft catechism. It helped that all of them were familiar with the game and many were already experienced from years of game play.

I was surprised by how well the students were able to listen while also playing a video game. I could teach whole lessons while they had the controllers in hand, and if I asked them to repeat back some of the devotional I’d read, they could typically repeat it back and respond thoughtfully, all while they were arranging layers of red stone on the screen.

I’d already observed such multitasking at home with my kids, so I should not have been surprised. Still, it was startling to realize how differently my GenX brain is wired than theirs. These kids have grown up being social while playing games with friends.

I was also surprised that each Sunday some of the kids were content just to watch their peers build in Minecraft. They did not all feel the need to play for themselves at all times. The fun and learning happened primarily in the conversations that emerged as the students watched each other play.

I was stunned by the creativity the class poured into their first churches. One group built a baptismal font that flowed up into the attic. Visitors could swim in the font, and when they arrived upstairs they found a memorial shrine where they could leave flowers to honor the dead. Nearby, a section of the catechism sat on a lectern: Luther’s explanation of the Apostles’ Creed.

Another group built a hidden church under their church building, reminiscent of the underground churches of early Christianity. There were altars, pews, mail slots, food pantries, a fishing pond, and even a rainbow wall between the churches to symbolize our community’s embrace of LGBTQ people.

At the end of the students’ first round of building catechism churches, we devoted some class time to processing the experience through a series of questions. What was it like not to have everyone get access right away? What has it been like to build as a team? What has been hard about this? What has been fun about it? What have you learned about the catechism while copying it for the stations in your Minecraft church?

I processed the experience internally, too. The students’ church building didn’t happen as quickly as I would have expected. Like any sandbox, Minecraft offers a blank slate and millions of options for the builder’s imagination to work through. As the teacher and host, I had to learn that it’s not a good idea to rush the process. Give it some time.

I also realized how much the project’s success was rooted in the improvisational mind-set we all brought to it. On the first day of class I might have responded to the joke about Minecraft catechism with a dismissive laugh. Instead, I paused, took a breath, and asked, “What would that look like?” As Minecraft catechism became a reality, we tried to come up with rules that would allow creativity rather than stifle it. The goal behind our rules was to say yes as much as possible so there would be space for everyone to see what emerged as we worked together.

The art of comedic improvisation relies on agreement. Tina Fey describes it this way: always say yes to whatever your partner is doing. Our experiment with Minecraft catechism reinforced my larger sense that improvisational agreement is crucial in the art of creative ministry. This is particularly true when it comes to the church’s relationship with new manifestations of media and technology.

One of my favorite groups that uses a framework of agreement to bridge divides is the Civic Imagination Project at the University of Southern California. In its recent publication Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination, project leaders Henry Jenkins, Gabriel Peters-Lazaro, and Sangita Shresthova highlight examples of positive social change arising through deep engagement with new media and popular culture. They quote bell hooks: “It’s exciting to think, write, talk about, and create art that reflects passionate engagement with popular culture, because this may well be ‘the’ central future location of resistance struggle, a meeting place where new and radical happenings can occur.”

Convincing church folks to incorporate new media into their sense of mission isn’t always easy. I’ve found it helpful to make the case using analogies to forms of media they’re more familiar with. The Christian Century isn’t just a magazine about religious life; it’s one part of our shared life of faith together. Similarly, life on social media isn’t just a marker that points to ministry happening elsewhere; it is a form of ministry. The same framework of agreement applies in both cases: each is an extension of the life of faith in community, not simply an empty vessel that delivers the faith (or corrupts it).

Minecraft catechism wasn’t the first time my congregation thought about our ministry in relationship to the games people play on handheld devices. In 2016, we discovered that the creators of Pokémon Go had established the space just outside the door of our church office as a PokéStop—a designated space that players seek out using their phones and the spot’s GPS coordinates. Almost immediately, a steady stream of visitors began coming into our parking lot, both in cars and on foot, and pausing at that particular spot to play the game. The spot became so frequently used by players that it was upgraded from a Stop to a Gym (which makes the game more challenging and the rewards higher).

My congregation didn’t ask to host a PokéStop. But we were committed to an improvisational mode of ministry, so we started thinking about ways to say yes to the augmented reality of our church grounds. On hot days we set up a water station near the Gym. There’s a welcome sign and an invitation to rest under the shade of a tree. Now that we have a prayer labyrinth on the church grounds, we might consider new signage that invites players to use the labyrinth.

The spot in our parking lot has become so popular with Pokémon Go users that it was recently upgraded again, from a Gym to a Raid (a Gym that groups of players can use together, not unlike a Minecraft Realm). My family has even joined a local Pokémon Raid group so we can find and capture rare Pokémon at area parks. It’s not necessarily a direct evangelism strategy, but it does keep us alert to the ways our neighborhood is layered with new media.

Saying yes to new media doesn’t require diving into its most complex forms, however. A lot of improvisation can be done with the media platforms parishioners already inhabit, like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

What might it look like to imagine these platforms as extensions of ecclesiological space? Last year, this was a theoretical question. Now, in the face of a global pandemic, it’s suddenly very real. Congregations have been forced by social distancing into an improvisational framework, and creative answers are emerging.

Church leaders have scurried to learn how to livestream worship services, host Bible studies on Zoom, conduct calls with sick parishioners using FaceTime, and implement communications platforms like Constant Contact for robust congregational care. Congregations have recognized that their media resources—podcasts, livestreams, blogs, websites, chat groups, email lists, ham radio systems—aren’t a threat to the community or a burden to overcome. They can be lifesavers, sometimes even literally.

My congregation has enthusiastically embraced the live-stream worship services we’re broadcasting during this uncertain time. Some of the most creative engagement has come from the youngest among us. Several families are breaking out bread and wine and sharing communion after the service. Other families give their children Play-Doh in order to have a hands-on activity while worship happens. These Play-Doh creations have included “Social Distancing at the Well,” “Baby Easter Egg Jesus,” and “Toilet Paper. Water. Christ. Love.”

Our confirmation class’s location in digitally mediated space is also paying dividends. I can easily get a note out to the group and encourage them to log in to the Minecraft Realm and start work on a new project. We’ve also used a set of lessons discussing videos from BibleProject, which families can watch and discuss at home.

I’m guessing that Luther would be entirely on board with these ecclesial uses of new media. At the beginning of the Reformation, Wittenberg had only one printing press. By the end of the 16th century, Luther’s rural town had published more books than any other city in the Holy Roman Empire.

The printers in Wittenberg didn’t do this just because it was lucrative. They saw it as a form of ministry. Whether they were publishing essays written to change the way people thought or posters designed to hang in kitchens across Germany to help the paterfamilias educate his family, these printers were making use of an emerging technology in an improvisational mode of agreement. The same holds true for Paul the apostle, an early adopter of the codex—what we now call books—to keep Christians connected across distances.

Rather than approaching new media as something to be fenced or worried over, the church can be at its most creative when it sees emerging virtual platforms as extensions of ourselves into new spaces—so the church can be present in radically new ways in every space.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Catechism games.”