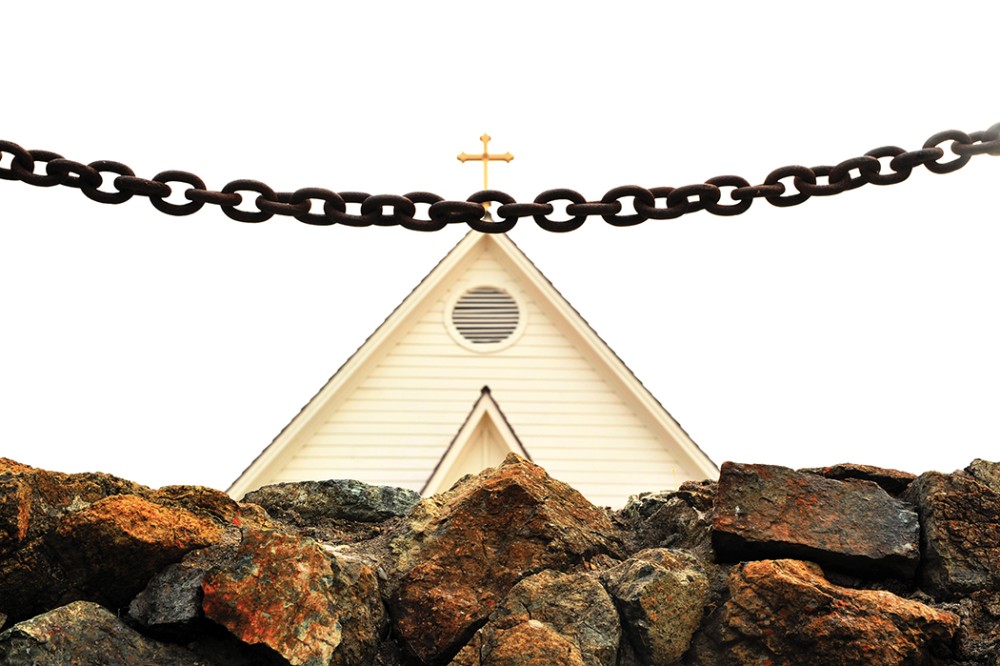

Church security and the risks of hospitality

My church has Fort Knox-level safety protocols. Why?

Every day at noon, an Atlanta church I served would open its Red Door Café, offering a free meal to the city’s homeless women and men, day laborers, temporary office workers, and anyone else who wanted a meal. We didn’t check IDs or immigration status. We didn’t screen for alcohol or drugs. We didn’t search bags for concealed weapons or contraband. We just opened the door to hungry people. Isn’t that what churches are supposed to do?

A few members of the congregation had fears about the clients of the Red Door Café and questioned the wisdom of granting strangers access to the church building. A few neighbors chafed at the resulting traffic in our otherwise quiet neighborhood. But most who knew of the Red Door Café applauded and welcomed its mission.

I now serve a parish in a quaint suburban village. Our building is tucked away from the highway. The nearest bus stop is more than a mile away. Our landscaped five-acre property looks like a nature preserve. The people who enter the church are mostly known to us. Nevertheless, this church has installed security protocols worthy of a Federal Reserve bank.