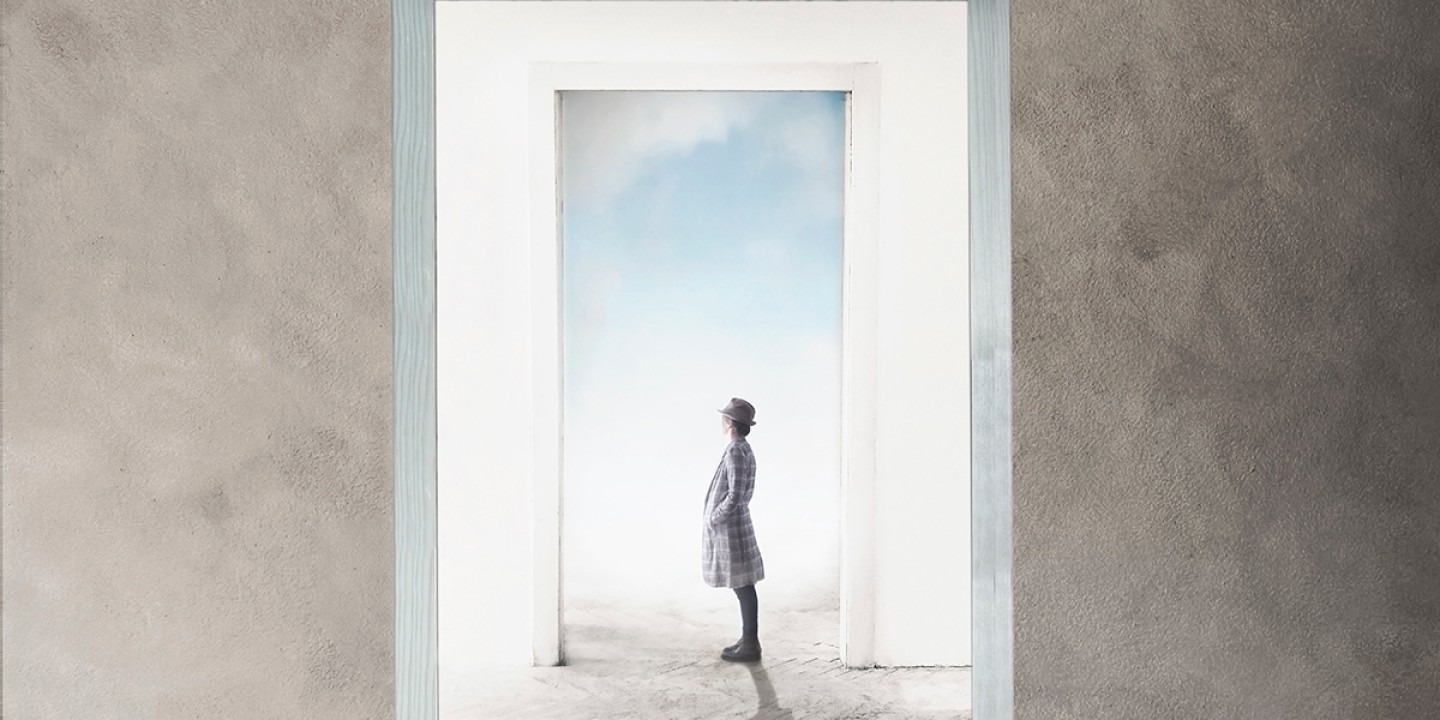

A father and his dying daughter came to see me. They wanted different things.

Sometimes truth is better than comfort.

Some time ago I got a call from an intermediary. He knew a bit about my work in the church. He had some sense of what theology was about. He knew a lot about medicine. And he wanted to put me in touch with a family who needed my help.

He explained the situation. “She’s just 18,” he said. “It’s a tumor,” he explained. “She’s doing really well,” he assured me. “It’s really her father I’m worried about. He’s taking it worse than anyone.”

I said what anyone would say. “How can I help?”

Like many who bear two identities, I enjoy the crossover between being a pastor and a professor. There are downsides: those on both sides who assume the other calling is idle or that you can’t possibly be doing either job properly. But there are many upsides, such that I can’t imagine doing one without the insight offered by the other.

It looked like the man who called had landed on me precisely because of my dual vocation. He walked into my office with two bewildered people: a young woman, who’d gone through the gamut of last-gasp lifesaving procedures, and a father, who was punch-drunk with crushed plans and devastated dreams. Before departing, the intermediary said, intently, “They need hope.” I had my commission.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I don’t specialize in small talk, and I was apprehensive as to how to present myself, given that I’m a person with no medical knowledge—perhaps the first such person the young woman had met in a while. So I was relieved when the father took up the mantle. “We’re—she’s—interested in theology. She’s planning to study it at college. We’re wondering if you can tell us about what theology is and what kinds of things you study.”

I was starting to understand my part in this play. My job was to offer the prospect of a happy college career, to transcend the bleakness of the medical outlook. I wondered whether the young woman had got the memo about this. Only one way to find out. “Tell me what you know about theology,” I ventured, seeking to build on what was already there.

“Well, I guess it’s about God, and beliefs, and . . . ” She looked at me pleadingly, willing me to complete the sentence for her. Now I knew. This was a game we were playing for her father’s benefit. She was much closer to accepting the truth than he was. He desperately needed something to reach for, as if one could jump over death like a gymnast pivoting around a horizontal bar to leap over a wall. She wasn’t looking for any such bar.

I didn’t have much time to decide on a strategy. I went for the truth that dare not speak its name. “May I tell you why I love theology? It’s because it’s about the things that really matter. Why are we here? How many universes were there before this one was created 14.8 billion years ago? How can there be life if there’s also death? Can we trust the one who put us here? Do we get to find out why we’re here, and when we do so, will it be too late? Do other people really exist, or is reality all in our imagination? Are we all in God’s imagination—did God make us up? Are we God’s dream, and is that why things get so distorted and unfair and out of shape, like they do in dreams?”

I paused. The father seemed to be thinking, Yeah, all that guff—waste of time if you ask me. But the young woman saw where I was going. She half chuckled. “What else is it about?” she asked, but I sensed she was really saying, “Thank you for talking the only sense I’ve heard since all this started.” My risky maneuver seemed to be working.

I went on. “Well there’s also ministry. Ministry is where you take those questions and see how they play out in people’s lives. You say, ‘I wonder what it feels like to hold your grandson when you never got to hold your daughter?’ You add, ‘I wonder what’s the first thing you’re going to do when they let you out of jail.’ You explore, ‘Tell me about what you ponder when you’re awake in the night.’ You ask, ‘When you spend your whole life trying to escape something, is it a relief when it finally happens?’”

I’d sailed too close to the wind at that point. The father reached for his coat: “We’ve taken up enough of your time.” The young woman looked at the floor as if it were a glass she could see through. We said our good-byes.

I sat in my chair reflecting on the word comfort—the thing I sensed the father wanted from me. I’d disappointed him. But I think the young woman wanted truth. Someone to be with her as she faced the unknown and did not run away.

Six days later the intermediary called. “I’m sorry. She died. Thanks for taking the time.”

I was shaken but not surprised. She knew. She’d come along to see me to indulge her father. Somehow we’d made a pact to face the truth together, right in front of her father—until he spotted it and put a stop to it. I hoped I’d given her something better than comfort, something that bears all things, endures all things, runs away from nothing. And I wondered how often, in ministry, I’d taken the risk of giving the young woman what she needed—and how often I’d settled instead for giving her father what he wanted.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Something better than comfort.”