Frozen River

I’ve covered the Sundance Film Festival many times and can say with reasonable authority that the movie lovers who brave Utah winters to see world premieres are some of the easiest audiences I’ve encountered. I’ve seen parka-clad devotees cheer for films that are run-of-the-mill family squabble movies and give standing ovations to politically correct coming-of-age stories that would never see a movie screen outside of Park City. As a result, I’m always dubious when a film has the Sundance seal of approval stamped on it.

So I’m especially gratified to report that I enjoyed Frozen River, which won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2008 Sundance Film Festival. True, this film contains many of the story elements that constitute a Sundance favorite (screwed-up families, addiction, racial intolerance, a struggle against the system, etc.), but writer and director Courtney Hunt doesn’t allow these familiar themes to overwhelm the script and turn it preachy. Rather, she uses tiny bits of these and other issues to pepper an already strong and believable script.

The film, which is an expanded version of a short film that Hunt made in 2004, plays out along the Canadian border in upstate New York and centers on two tired and frustrated women. Ray Eddy (Melissa Leo) is a stressed-out mom trying to raise her two sons, ages five and 15, by herself (her gambling-addicted husband has flown the coop with the family’s savings). Her dream, which we learn about in the first act, is to purchase a new prefab house so they can move out of the cramped trailer they are living in. But this dream seems increasingly unattainable since she can’t get a full-time position at the Yankee Dollar discount store where she works and she refuses to let her older son drop out of school and get a job.

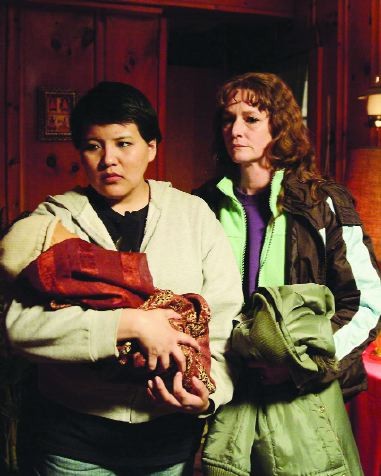

Enter Lila Littlewolf (Misty Upham), a single Native American mom whose life is even more desperate than Ray’s. She too lives in a trailer, but she earns her income by smuggling illegal immigrants from China and Pakistan across the Canadian border into the U.S., using the Mohawk Indian reservation as her cover. Crossing here is easier than at other places on the border, since the border police have no jurisdiction on the reservation, but the site presents its own risks—the tribal chiefs don’t condone smuggling and are suspicious of Lila. Lila too has a dream, which involves getting her baby back from her pushy in-laws, a subplot that is underdeveloped.

An incident involving a stolen car brings these two women together, and soon, despite their inherent distrust of each other (“I don’t work with whites,” seems to be Lila’s credo), they are running illegals for cold hard cash. The irony of course is that the job is safer with Ray involved, as she is white and therefore less likely to be pulled over by the police.

The film’s obvious strengths surface during the late-night pick-ups and drop-offs, when Ray and Lila are alone. Not only must they risk their lives driving across the frozen St. Laurence River to avoid the authorities (the river is a metaphor that runs through the film), but the drive gives them time to feel each other out. They never say much, but the looks on their faces as they watch the helpless illegals get shuffled from cabin to car while they count their cash speaks volumes about all of the hopes and regrets in their lives.

Frozen River was shot on a tiny budget over 24 icy days and nights, which may account for its neorealist glow. The film is soft-spoken and understated, filled with striking cinematography by Reed Morano that takes full advantage of the frosty air. It is at its best when it is subtle and realistic, and on thinner ice when it incorporates a few melodramatic subplots. (You’ll know them when you see them.) The actors, many of them not professional, are convincing and follow the lead of Leo and Upham, who are somehow able to convey bravery and fear in a single sigh.

Frozen River is too smart a film to guarantee happily-ever-afters for this odd couple, but it does suggest that the long journey up river is a lot easier when someone you trust has your back.