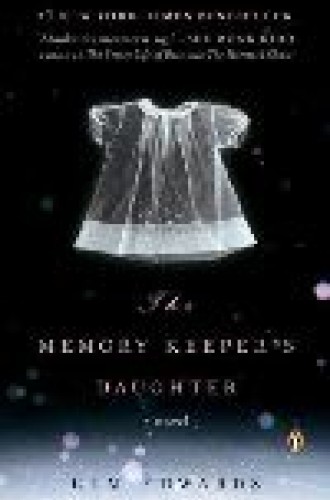

The Memory Keeper's Daughter

On a winter night in 1964, an unexpected blizzard forces Dr. David Henry to deliver his own twins. The firstborn child is a healthy boy; the doctor immediately recognizes that the second, a daughter, has Down syndrome. While his wife, Norah, is still sedated, he gives the baby girl to an attending nurse and tells her to place the child in an institution. When the mother rouses, David forgets his rehearsed words and utters, “Oh, my love. . . . I am so sorry. Our little daughter died as she was born.” From these few simple sentences springs a heartrending novel of regret, resilience and redemption.

There are no villains in this story. With lyrical prose, Kim Edwards paints an honest portrait of the human condition. In every character we see wheat and tares sown together; we watch good intentions go awry; we wait for confession to crack open the soul. Like the chorus in a Greek tragedy, Edwards repeatedly reminds readers that David’s dark secret has sealed each character’s fate. She doesn’t condemn her characters but treats them with respect and compassion.

The Memory Keeper’s Daughter is a best-seller and a book club favorite with plenty of fans among churchgoers. One theme that resonates with readers is the way experience profoundly shapes moral vision. David’s deception is rooted in his hard-scrabble past. He grew up poor in the mountains of West Virginia. His mother was consumed by caring for his younger sister, who had a heart defect and died at age 12. Years later, David gazes at his newborn daughter and can only see history repeating itself. “This poor child will most likely have a serious heart defect,” he tells the nurse. “I’m trying to spare us all a terrible grief.”

This story prompts rich reflection on the insidious power of family secrets, and it invites us to ponder the preemptive strikes sometimes deployed to protect loved ones from suffering. Fear can motivate drastic action to secure a future for ourselves and for those we hold dear. But life-giving care flows from love, not from fear, as characters in this novel come to discover.

David buries his sorrow in long hours of work as a physician. He cultivates a detached, spectator’s view of life, aided by a camera called “The Memory Keeper,” a gift from his wife. Haunted by the presence of her absent daughter, Norah finds herself drifting farther and farther away from her husband. In her portrait of Norah, the author shows the long reach of private grief that is unconverted by communal rituals of mourning. David, Norah and their son, Paul, live isolated lives under the same roof, as separate from one another as they are from the missing member of their family, Phoebe, who is raised in a different household in a distant city.

Phoebe has a savvy caretaker and strong-willed advocate in Caroline, a modern-day Hagar who, aided by down-to-earth angels, makes a way through the wilderness to preserve the life of the rejected child. Through alternating chapters the author depicts each twin growing up, unaware of the other’s existence. For her part, Phoebe flourishes in her adoptive family, nurtured by a web of institutions that includes a household of faith.

The Memory Keeper’s Daughter realistically depicts the challenges and blessings of sharing life with someone who has Down syndrome. My younger sister, Judy, born in 1960, has this genetic abnormality. “Don’t even take her home,” friends and relatives urged my parents. “It won’t be fair to the two healthy sons you already have.” A seasoned obstetrician counseled otherwise. “Take her home,” he advised. “Care for her and love her as you would any child. She’ll be slow, but you’ll all learn together.” Almost 50 years later I’m still learning from my sister, who’s as eager as grown-up Phoebe is to get married. With Judy I’m learning how the life of Christian faith prepares people to suffer wisely, for good cause and with caring companions. That’s a lesson for the David Henry in every one of us.