No Country for Old Men

Joel and Ethan Coen accomplish what Cormac McCarthy set out to do in his bombastic 2005 novel No Country for Old Men. The movie by the same name is a portrait of the moral void of post-Vietnam America (it’s set in 1980). The title, which implies a nostalgia for vanished old-world values, is taken from Yeats’s poem “Sailing to Byzantium.”

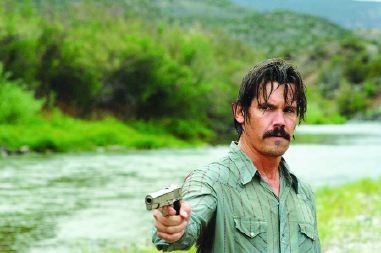

That void is embodied in a psychopathic contract killer named Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), who treks across Texas with the relentlessness of an unstoppable automaton from a sci-fi thriller. He’s chasing down an adventurer named Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), who has made off with a suitcase of money he found at the site of a drug deal gone bad. Moss is a flawed hero, a decent man (and a Vietnam vet) who makes a terrible, irrevocable mistake. He and Sheriff Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), who tries to get to Moss before Chigurh can, still live by a moral compass. Chigurh, who sometimes tosses a coin to determine whether his victims live or die, doesn’t.

The Coens, who co-wrote the screenplay as well as codirected it, are extremely faithful to the book, but they pare down McCarthy’s gab so the actors can bring some meaning and plausibility to what remains. Much of the movie’s power derives from the way that they and cinematographer Roger Deakins shoot the beautiful, airless blankness of the Texas horizon, which seems to go on forever and appears as if it might house all the conundrums no mortal can ever puzzle out. As the characters move, however purposefully, across all that flatness, it almost swallows them up—except for Chigurh, who comes to serve as its emblem.

Bardem has the showpiece role, and Beth Grant throws herself into the showy little part of Moss’s ornery mother-in-law. Otherwise, the actors get their effects by following F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famous dictum that action is character. One never catches them acting, so it’s not evident how difficult the roles are that Jones, Brolin and Kelly Macdonald (as Moss’s nervous, devoted wife, Carla Jean) have taken on.

As he did in In the Valley of Elah, Jones plays a sorrowful man whose old-fashioned male approach to the world has been outrun by horrors he can’t get his head around. He takes his fabled deadpan readings down another notch, removing any glimmer of show-biz self-consciousness. Brolin, who stalked through American Gangster like a poster-board villain, is effortlessly convincing here as the sardonic Moss, whose heroism lies not only in his craftiness at eluding Chigurh for as long as he does but in his unflinching acceptance of responsibility for his own actions. The terrific young Scottish actress Macdonald applies her classical training to a character from a culture remote from her own: her work is not only delicate and poignant, but Texan to the life. And in a vivid example of on-the-money character sketching, Woody Harrelson animates a couple of scenes as the confident, amused hunter sent to curtail Chigurh’s killing spree.

Casting the handsome Spanish actor Javier Bardem as Chigurh (who is Polish in the book) is a gamble that pays off: even the trace of an accent that Bardem can’t flush away adds to the impression that nothing about this man can be pinned down. He sports a truly awful hairstyle—an orange-brown helmet with razor-cut bangs. His eerie, almost canine focus—his auditory and olfactory senses seem more highly developed than an ordinary human’s—transcends the look. The most unsettling part of his presence comes from those high-beam eyes.

Who would have guessed that the Coens, purveyors of cooled-out ironic entertainments, masters of style for its own sake, could come up with work of this caliber? There are very few false steps in this movie (the final scene, which makes the error of confronting movie-western mythology head-on, is one), and they don’t dilute the experience of the film. It’s a classic—the most original, profound and chilling variation on the conventions of the western since the heyday of Sam Peckinpah.