Mr. Chappelle's neighborhood

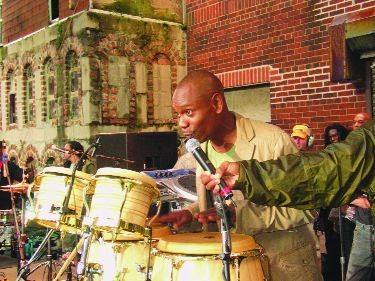

If there is a movie that can make you feel optimistic about the possibilities of forming community in America, Dave Chappelle’s Block Party is it. In September 2004 Chappelle, an African-American stand-up comic, celebrated his $50 million contract with Comedy Central by throwing a free hip-hop party in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. A crew of musically gifted pals performed for thousands of guests. Many came from his hometown of Yellow Springs, Ohio, with Chapelle providing the bus and hotel accommodations.

The movie, directed by Michel Gondry (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), is a loose-limbed account of the event as well as the process that led up to it—like Chappelle’s booking the marching band from Central State (Ohio) University.

Inclusive is the word for Chappelle’s approach. He goes out of his way to gather celebrants of all ages, including the middle-aged white ladies who run a convenience store and the aging white hippie couple who occupy the “Broken Angel,” a wonderfully dilapidated house on the corner that is earmarked for the block party. They decline; they don’t care for rap. But neither Chappelle nor the movie quibbles with their taste.

Block Party pays homage to American variety and American eccentricity. The interaction between the party’s host and the “Broken Angel” owners is playful and sweet-spirited. So is Chappelle’s stand-up routine, even when he burlesques relations between the races. His determination to keep the event in the sunshine corner is echoed by the beneficiaries of his largesse. In one charming sequence, a couple of black teenage boys tell how they refused to get into it with a white man who made a racist comment because they were keeping their eyes on the prize—the block party.

There’s also a lovely rapport between Chappelle and Luz Grice, who runs a day-care center and is proud to introduce her children. Grice balances a commitment to her charges that seems like a holy mission with a schoolgirl smile that bubbles through her face like a fresh-water spring.

One of the alumni of the center is the murdered rapper Biggie Smalls, who in this movie is presented not as a martyr or even as a casualty but as an artist to whose talent the kids can aspire. The touching tribute the movie pays to him underscores his loss without diminishing the film’s jubilant tone.

The musical acts are terrific, and Gondry shoots their contributions with appreciative warmth. They include the militant rappers Dead Prez, the sweet-voiced singer and guitarist Kanye West, the former rapper—now first-rate stage and film actor—Mos Def (the costar of the new 16 Blocks), and three women who make you both stare in wonder and grin with delight. Erykah Badu sings the lovely “Back in the Day” under a massive Afro weave; when the wind whips up and threatens to blow it off her head, she tosses it like a musician dealing efficiently with a broken guitar string and then jumping back into the number. Big-boned, barrel-voiced Jill Scott is an even more formidable force of nature than that wind. And in arguably the most amazing moment in the movie, Lauryn Hill devises a way to get around her record company’s refusal to let her perform her solo output: she, Wyclef Jean and Pras stage a reunion of their celebrated band the Fugees. The boys and girls from CSU’s marching band look blissed out when she re-creates her celebrated cover of Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly.”

Gondry keeps returning to the college kids, who are all black. After the Fugees’ set, some of them venture onto the stage to hang out with Wyclef, a Haitian émigré who talks about teaching himself English when he arrived in America and, without a hint of condescension, invites them to tell him individually what they would do if they got elected president. Congratulating them on going to the university, he urges them not to blame whites for whatever obstacles they may have encountered and trumpets the importance of libraries.

His words build on Chappelle’s generosity, which isn’t color-blind but is open-armed and open-hearted, and on the all-embracing attitude of Luz Grice, who wants to make sure Chappelle knows that her day-care center is now serving Caucasians as well as African Americans and Hispanics. The neighborhood served by this block party appears to be about as big as all outdoors.