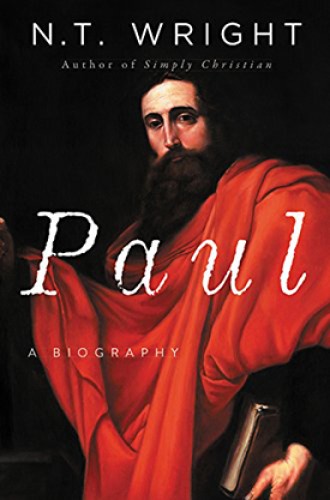

N. T. Wright’s creative reconstruction of Paul and his world

Wright tells a great story. Would the apostle recognize it?

The writings of N. T. Wright are so voluminous that one might justly wonder: Why yet another book on Paul from this prolific author? The answer lies in the subtitle: A Biography. In distinction from his earlier works on Paul’s letters, here Wright tells us: “We are searching for the man behind the texts.” The audacity of that goal should give us pause. Even in the case of living authors, their identity, thoughts, formation, and motivations remain necessarily hidden, even to themselves to some degree. How much more so when the writer in question lived some 2,000 years ago?

Undeterred, Wright presses on in the name of “history,” which he repeatedly describes as “thinking into other people’s minds.” For Wright, such thinking (which he distinguishes from “psychology,” albeit without clarification or warrant) depends in turn on a reconstruction of Paul’s context and setting. That reconstruction is the starting point for this “biography,” and in Wright’s view it is an essential key to understanding Paul himself.

Wright begins by setting forth his understanding of history as a discipline and of Paul’s own context in particular. His goal is to invite modern readers to live in Paul’s world so as to understand what he is saying. Along the way he paints a vivid picture of young Saul growing up in Tarsus, zealous for the Torah and for Israel, learning at his father’s knee to distrust the goyim. Wright makes a great deal of the stories of Phineas and Elijah, along with the stories of the Maccabean martyrs, as role models for young Saul, whom he characterizes as driven by violent zeal. Indeed, we can know a good deal of what motivated Saul through reconstructing the “single story” of Jewish hopes in the first century, running from Adam’s fall to the call of Abraham, to the disobedience of Abraham’s heirs, to exile and a future restoration to be accomplished by the Messiah. Those who have read Wright’s other work will find themselves in familiar territory here. For Wright, everything in Paul’s letters fits into this dominant narrative of exile and return, dependent on covenant loyalty.

This manufactured Jewish worldview is the first source for Wright’s biography of Paul. The second source is Paul’s speeches in the book of Acts, both their content and their narrative frame. Those speeches, which were almost certainly written several decades after Paul’s ministry, surely tell us how Luke saw Paul and wanted to portray him. But Wright uses them as clues to Paul’s own thinking—to the man behind the letters. Wright’s broad-brush construction of Paul’s social milieu together with Luke’s account of Paul’s life set the context for the book’s interpretation of Paul’s own writing.

The bulk of this lengthy volume traces Paul’s travels and discusses his letters in the setting of those travels. The chapters, titled after Paul’s geographical locations, include discussion of the letters Paul wrote from those locations. This approach allows Wright to harmonize the letters and Acts as much as possible and also to speculate on correlations between the content of the letters and Paul’s experiences in the various locations. The results are sometimes striking, sometimes illuminating, and frequently speculative and creative.

To give one example, in his discussion of the Corinthian correspondence Wright alternates between the letters and Paul’s experiences in Ephesus while he was writing the letters. He maintains, in fact, that Paul was imprisoned for a lengthy period of time in Ephesus. Acts mentions no such imprisonment; Wright bases his theory on 2 Corinthians 1:8–9, where Paul says he experienced such affliction in Asia that he felt he had received a death sentence. Wright further suggests this Ephesian imprisonment was the occasion and location for Paul’s writing of all the prison letters, beginning with Philippians, then Philemon, Colossians, and finally, Ephesians itself, which Wright thinks Paul wrote from Ephesus as a circular letter for the churches. This is a provocative thesis, impossible to prove or to disprove. It allows Wright to paint a poignant picture of Paul suffering through the dark and cold of a winter imprisonment, during which the apostle put his roots down deeper into an affirmation of Christ’s lordship, such that the writing of the prison letters “grew directly out of the struggle Paul had experienced.” The image is appealing; the evidence is thin.

Indeed, Wright is at his best when his claims are most muted and he investigates possibilities without making authoritative claims. For example, with respect to possible Pauline authorship of the pastoral epistles, he explores the question of whether Paul might have traveled west from Rome to Spain, and/or traveled east. The discussion is refreshing for its open-ended approach to the evidence and the difficulties in making sense of the limited data we have, and for its candor about what we do not and cannot know. Wright concludes, “Paul had to live with a good many ‘perhaps’ clauses in his life. Maybe it is fitting that his biographers should do so as well.” Would that the rest of this lengthy biography had more “perhaps”!

Written for a popular audience and not for scholars, the biography is an easy read, in part because it is repetitive and makes sweeping claims without detailed argument, but also because it is written in the style of a public speaker and, at times, of a seasoned preacher. The result is a lively, vivid, moving, and occasionally humorous picture of Paul and his fellow believers as living, breathing, feeling, struggling human beings. Reminded of Paul’s close partnership with Barnabas, for example, we can hear the pathos in his exclamation that “even Barnabas” was carried away to hypocrisy by the men from James who came to Antioch (Galatians 2:13). Paul was not a cipher or a talking head but a complex, passionate, and immensely hardworking missionary who took great risks and suffered both emotionally and physically as he traipsed around the Mediterranean world. Wright gets the point across with considerable flair.

Along the way Wright argues rightly that “what we call ‘theology’ and what we call ‘sociology’ belonged firmly together” in Paul’s ministry, which means that crossing social boundaries is central to the gospel. For example, in Galatians 2,

if Peter and, by implication, those who have come from James try to reestablish a two-tier Jesus Movement, with Jews at one table and Gentiles at another, all they are doing is declaring that the movement of God’s sovereign love, reaching out to the utterly undeserving (“grace,” in other words), was actually irrelevant. God need not have bothered.

In other words, faith is not simply mental assent. Its embodiment is necessarily interpersonal and public, not otherworldly and private. Theology and practice go together. These are points on which almost all contemporary scholars of Paul would agree.

But Wright’s method of constructing a grand narrative, which he calls “the quintessential story of Israel,” and then making it the necessary framework for understanding what made Paul tick has some serious problems.

In the first place, despite Wright’s frequent assertions that “we must avoid oversimplification,” this narrative is drastically oversimplified, compressing the diverse and even competing voices in first-century Judaism into one strand of thought and then claiming that Paul must have thought along those lines. Any pastor who has gone into a new church thinking he or she knows its story and therefore can predict how people will think quickly learns the folly of such generalized assumptions. And that is in the present time, in direct encounter with a living community. How much more complex and elusive then is our attempt to think our way into the mind and emotions of Paul! Starting not with Paul’s letters but with a generalized picture of Paul’s context, Wright is sure to get some things wrong.

For example, the Paul who wrote Galatians 6:14–15 might be surprised to learn that his “deep inner sense of what made him who he was” was that “he was a loyal Jew.” To the contrary, he says, “Far be it from me to glory except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world. For neither circumcision counts for anything, nor uncircumcision, but a new creation.” Wright gets around this difficulty by arguing that Paul redefines “Jew” in terms of loyalty to the Messiah Jesus. But the trouble is this: How far does such Jewish identity extend? In Paul’s context, can a loyal Jew say that circumcision, keeping kosher, and Sabbath observance are optional? That sometimes he can behave like a Jew and sometimes like a gentile, “outside the law” (1 Cor. 9:20–21)?

I suspect the Jews of Paul’s day were not convinced, nor would Jews today be convinced. Rather, Paul seems to sit loose to his Jewish roots. Depending on his purposes, sometimes he emphasizes his Jewish identity and sometimes he relativizes it; the very ambiguity suggests this is not central to his deep inner sense of himself. What is unambiguous is that he is “in Christ,” and Christ dwells “in him.” This is the beginning and end of who he is. For contemporary American Christians this is a prophetic word, speaking into all the conflicting identities we profess and challenging their capacity to override our unity in Christ.

That leads to the second difficulty in beginning with claims about Paul’s context. Paul’s message is made to fit into a preexisting history rather than seen as something that begins with Christ. That means, in practice, that the message is constrained by the past and develops out of it. The world-shattering event of God taking on flesh, dying on a Roman cross, and conquering death and sin becomes one act in a larger drama of salvation beginning with Adam and extending through the church to the eschaton. Wright depicts an apostle who reasons forward from Adam to Abraham to David to exile to Isaiah to an awaited restoration of Israel—and he repeatedly claims this is what Paul preached, although the letters do not support such an assumption. But what if Paul reasons backward from the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus as the Christ, so that all of history is gathered up into that event and only in that way is redeemed?

In the first account, the gospel arises out of a chain of events in history. In the second account, God does a genuinely new thing in Jesus, and that genuinely new thing breaks into history and becomes the vantage point for understanding everything that preceded it and everything that will follow. From that vantage point one then sees that God, whom Paul identifies as the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, has indeed been acting in the events leading up to the present, but one sees that rightly only through the lens of Jesus Christ. It is as if the cross and resurrection shine spotlights on certain parts of Israel’s scriptures and leave others in shadow.

The difference may seem slight, but in fact it has profound consequences for ministry. Beginning with the past constrains the present, limiting it to what has already been or at least what can be imagined based on prior experiences. Beginning with Christ’s death and resurrection offers radical hope for new beginnings. Indeed, Paul describes himself as “forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead” (Phil. 3:13). His identity is being pulled into the future, not defined by the past. This absence of nostalgia or evolutionary thinking certainly challenges churches that pride themselves on their long histories and resist change, but it also inspires hope and animates ministry among those whose histories cannot yield any positive perspective on the present. Such a perspective doesn’t mean abandoning the past, let alone denying or erasing Israel’s history; it means seeing it through the radically new lens of crucifixion with Christ and resurrection hope.

Additional pastoral problems arise from Wright’s treatment of Luke’s versions of Pauline speeches in Acts as windows into Paul’s thought. For example, he finds in Paul’s speech before Herod Agrippa (Acts 26) an “authentic sense” of Paul’s vocation, despite admitting that this is “one of Luke’s carefully crafted scenes.” The speech recounts Paul’s experience on the road to Damascus, including Luke’s version of Paul’s divine commission to open the eyes of the nations “so that they can have forgiveness of sins, and an inheritance among those who are made holy by their faith” in Christ (Acts 26:16–18). Wright then simply assumes that this message of forgiveness is central to Paul’s preaching. Such an assumption must be based on Acts, since the word forgiveness appears exceedingly rarely in Paul’s letters.

But for Paul, the problem is not that individuals and communities sin and need forgiveness; in fact, Israel had a system of atonement to deal with sins. The problem is that sin and its henchman death use even God’s good law to hold humanity captive, to deceive and to work death. In Paul’s letters, sin is rarely a verb denoting human action that needs to be forgiven, as if the primary problem were human wickedness. Rather, sin is a power that holds humans captive and lords it over them.

We can track this language in Paul’s letter to the Romans, for example. In Romans 2:12, 3:25, 5:12, and 6:15, humans are the active subjects of the verb “to sin.” As such, they accomplish (2:9), “do” (3:8), and “practice” (1:32, 2:1–3) wrongdoing. But by doing so, they demonstrate that they are “under sin” (3:9); they are not simply free agents making bad choices. Rather, their sinning demonstrates the reality of sin’s overarching dominance in human history. And in Romans 5:12–8:4, Paul reframes the story of humanity’s sinfulness within a larger narrative of bondage to sin as a “colonizing” power that holds humanity captive, entering human history in tandem with death (5:12), expanding exponentially (5:20), reigning over death (5:21) and in mortal bodies, using bodily members as weapons of unrighteousness (6:12–13), and paying out death to its hapless slaves (6:23). Sin now does what human beings did in the earlier narrative, “doing,” “practicing,” and “accomplishing” evil (7:15–21). If we take this language seriously, we are led to an account of Paul’s gospel in which the good news is more than forgiveness for individual or corporate wrong. It is deliverance from sin as a larger-than-life power that holds both individuals and societies captive.

This deliverance is great good news. It speaks into situations that a narrative of guilt and forgiveness simply does not address adequately, including addiction, oppression, abuse, cognitive impairment, injustice, and social blindness, just to name a few. Forgiveness certainly has an important part to play in the overall message of the New Testament, particularly in Luke-Acts. But it is not, of itself, adequate to address human suffering in its myriad forms. We need to hear Paul’s distinctive and far-reaching preaching about sin, its lethal use of the law, and Christ’s victory over it. To do so, we must allow his letters to speak on their own, without trying to harmonize them with other parts of scripture.

By using the speeches in Acts to tell us what Paul thought, Wright mutes Paul’s radical diagnosis of the human condition. That diagnosis is far more global than simply viewing Rome as the enemy. In fact, Paul talks very little, if any, about Rome or Caesar. They are not worth his notice, and they are not in view when he uses the language of bondage and freedom. Whereas Wright emphasizes Jewish antipathy to Rome and posits that Paul wanted to plant his gospel of Christ’s lordship in opposition to the imperial claims of Caesar, Paul sets his sights on enemies far greater than any human power or institution. The enemies, as he repeatedly says, are sin and death, and it is the brutal reign of these suprahuman powers that Christ overthrew on the cross, thereby setting humanity free. That is the regime change that truly liberates.

Wright’s epic biography of Paul ends climactically with Paul facing his own death and compares him to the great Rabbi Akiba, who prayed the Shema while being tortured to death by Roman soldiers. Wright imagines Paul praying a version of the Shema, naming God as the father and Jesus Christ as Lord. It is an affecting scene, with soaring prose culminating the final chapter of the book. Wright can preach. He can tell a great story, and he does. But is it Paul’s story? Or is it Luke’s story of Paul, amplified?

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Is this Paul?”