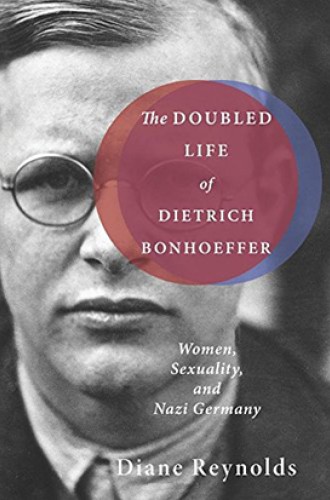

A more intimate portrait of Bonhoeffer

Diane Reynolds’s book would be worth its price for its insistence on noticing the women at every turn in Bonhoeffer’s life.

Midcentury biographical conventions encouraged the effacement of women’s lives. Since Eberhard Bethge’s monumental biography, Bonhoeffer’s story has been viewed as unfolding within a male-only world. Details of Confessing Church politics and theological analysis have animated decades of Bonhoeffer studies, but few scholars have looked deeply into the emotional, inter-personal, and psychological textures of Bonhoeffer’s life. Diane Reynolds looks beneath the surface.

The book would be worth the purchase price simply for its insistence on noticing the women present at every turn in Bonhoeffer’s life. Two such women are Elisabeth Zinn, Bonhoeffer’s neighbor and colleague in theological studies, and Berta Schulze, his personal and professional assistant in London. Reynolds demonstrates that Zinn and Schulze were genuine theological peers to Bonhoeffer, as Bethge’s biography hinted at. Most accounts of his life treat them (if at all) wrongly as his first fiancée and house-keeper, respectively.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It is, however, in exploring Bonhoeffer’s relationships with a central triad of women—and, at the center of his life, with Bethge—that Reynolds’s work moves into original interpretive territory. She dives into the theologian’s very close connection with his twin sister, Sabine, his collaboration with and dependence on his benefactor Ruth von Kleist-Retzow, and his puzzling relationship with his fiancée Maria von Wedemeyer.

Reynolds devotes to Wedemeyer a level of attention that no previous biographer has given, including an appendix tracing her life and the progress of her relationship with Bonhoeffer from 1935 to 1945. Wedemeyer’s agency, subjectivity, and energy leap from the page as Reynolds shows through meticulous reconstruction of their engagement how strained and confusing it surely was to both participants. The affection and, on Wedemeyer’s part, intensity of emotion evident in many letters mask a deeper incompatibility that would almost surely have led to the breaking of their engagement had Bonhoeffer survived the war.

Woven through these relationships with women is a central absence: any woman at the heart of Bonhoeffer’s sexual desire. Instead, Reynolds clearly shows Bethge’s centrality as the focus of Bonhoeffer’s relational affection and erotic energy. She respectfully diverges from Charles Marsh’s recent portrayal of Bonhoeffer as effete, sketching him instead as a “man’s man.” Although he depended emotionally on Sabine and those he tried to enlist into her role after her marriage, he was comfortable in the male elite of his privileged circles and—but for that odd disinclination to marry—very much a traditional male. A second appendix sketches Reynolds’s nuanced views on the contested questions of Bonhoeffer’s sexual orientation, his passionate bond with the apparently heterosexual Bethge, and his possible sexual activity. She considers thoughtfully that he may have been a committed celibate.

As Reynolds notes, the book’s attention to Bethge was not its original focus. Yet, investigating Bonhoeffer’s relationships with the women closest to him drew the author inexorably also to Bethge. For instance, her use of Sabine’s memoir as a primary source leads her to tug on a thread other biographers have overlooked—the fact that Bonhoeffer’s 1939 journey to New York included at least the possibility of Bethge’s soon traveling to join him. Reynolds traces the evidence in extant letters and Bonhoeffer’s June 1939 diary to propose that Bethge’s reluctance to leave Germany contributed to Bonhoeffer’s anxiety about remaining in the United States.

Her work thus opens the possibility that Bonhoeffer’s return to Germany was centered in this central friendship, not only or perhaps even primarily in the widely known spiritual call that pulled him home and into the conspiracy against Hitler. This is perhaps the most dramatic example of the kind of reevaluation Reynolds’s investigation makes possible. As she surfaces new data and reconsiders known facts, she connects the dots in ways other scholars will need to take account of, even if they disagree with any given conclusion.

In bringing into one volume so much data and insight on Bonhoeffer’s relationship, Reynolds offers scholars and admirers of Bonhoeffer a much fuller account of his humanity. A few errors and odd omissions do not substantially detract from what is overall a trustworthy account of the broad strokes of Bonhoeffer’s life. And while I quibbled at points with Reynolds’s evaluation of the data she so carefully explores, overall I find her interpretations both convincing and empathetic.

Reynolds’s interpretations intend not to supplant but rather to stand alongside the more typically theological readings of Bonhoeffer. Her book gives scholars a deepened appreciation of how consistently his theology embodies its own best insights: the insistence on this-worldliness, relational formation, and a passionate, confusing, and devoted polyphony of life and love.