The earnest, hilarious Al Franken

The senator's jokes are still funny, even if Trump has made his satire obsolete.

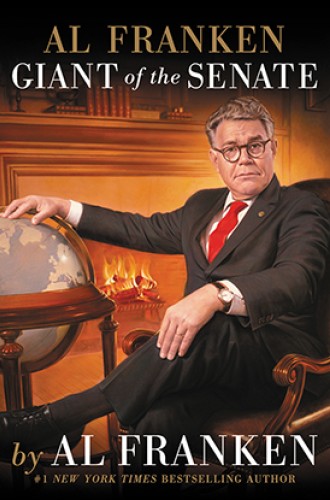

Al Franken is, despite the best efforts of reporters, Republican operatives, Senate colleagues, and his own staff, still funny. The memoir’s title and kitschy cover photo of Franken—longtime performer, writer, and producer for Saturday Night Live, later a gadfly of liberal radio and publishing, and now a twice-elected U.S. senator—reveals that he’s going to mock the self-importance of the genre and himself. But he’s going to do so without brutality, and even with a measure of fondness. The contrast between comedy and politics, and the modest absurdity it can create, gives this book its momentum, its life, and its invitation to serious political engagement.

In becoming a politician, Franken had to both use and live down his lifetime of joke writing. He revisits the out-of-context bits that were turned into political attacks when he first ran for the Senate in 2008. He details the pitfalls of entering the Senate (after a razor-thin victory in a recount and a lengthy court challenge by defeated incumbent Norm Coleman) with a reputation as a clown. In becoming a politician, Franken notes, he had to navigate and master an entirely different mode of interacting with his audience and his material. He learns how to avoid fights with reporters (“So treat the press like they’re alcoholics,” he tells a concerned staffer), how to deflect bad questions, and how to survive the mechanics of a scandal.

In the book’s funniest chapter, Franken narrates an intense inner struggle to restrain himself from making a sophomoric joke in a committee hearing on a bill that would have protected employees from losing their jobs because of their sexual orientation. He quotes the opening statements of his colleagues, interrupted by the blandishments of the angel and the devil perched on his shoulders, contesting the joke. “‘C’mon!!!’ the Devil yelled. ‘Tell the joke! It’ll kill!!!’” Eventually, the angel and the devil each sprout their own angels and devils, and the debate comes down to the angel’s devil (“we have to pick our spots” for jokes) and the devil’s angel (“No one over here is saying we should go for the joke every single time”). It’s a roaring piece of comic writing: a parody of political negotiation that plays on the lively contrasts of comedy and the dull contrasts of respectable political rhetoric.