Tolkien 2.0

The fantasy writer’s vast theological and philosophical universe is unfolding in the hands of artists, scholars, and game designers.

In 1956, Marquette University purchased the original manuscripts of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings for less than $5,000. At the time, no other institution had shown interest in J. R. R. Tolkien’s manuscripts. Thirteen years later, United Artists bought the movie rights from Tolkien for $240,000. Fast-forward to 2017, when Amazon paid a staggering $250 million for the rights to create TV adaptations. Just five years later, the Embracer Group acquired Middle-earth Enterprises (which holds the film and merchandising rights) for a record $395 million.

In just a few decades, Tolkien’s Middle-earth has transformed from a quiet literary legacy into a multimedia empire. And in 2025, I’d argue, we find ourselves in the midst of what could be called Tolkien 2.0—a new and expansive chapter in the ongoing story of Tolkien’s influence.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The signs of this moment are everywhere. The second season of Amazon’s The Rings of Power has aired (with three more expected), and a Silmarillion movie is slated for release in December. In the world of tabletop role-playing games, Free League Publishing’s specialized volumes on hobbits, dwarves, and elves for The One Ring RPG have been met with immense success, with 13,000 individuals backing just the dwarven setting expansion to the tune of $1.2 million. Meanwhile, HarperCollins is set to complete the release of the History of Middle-earth Box Sets—five monumental sets of Tolkien books edited by his youngest son, Christopher, which total around 6,000 pages. The anime film The War of the Rohirrim debuted last December, and next year Warner Brothers will launch The Hunt for Gollum as the beginning of a series of Lord of the Rings films, promising yet another new wave of Middle-earth content.

Among the many ways Tolkien has been celebrated, one stands out: the care and artistry given to his books. From the recent deluxe edition of The Silmarillion (complete with pull-out maps) to The Complete History of Middle-earth boxed set, Tolkien’s works are often presented in the most lavish ways imaginable. Catherine McIlwaine’s Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth is a beautifully curated volume, while Free League’s RPG manuals have redefined how we engage with Tolkien’s world, offering playful, artful experiences that invite role-players to participate as creators in the myth and as artists in their own right.

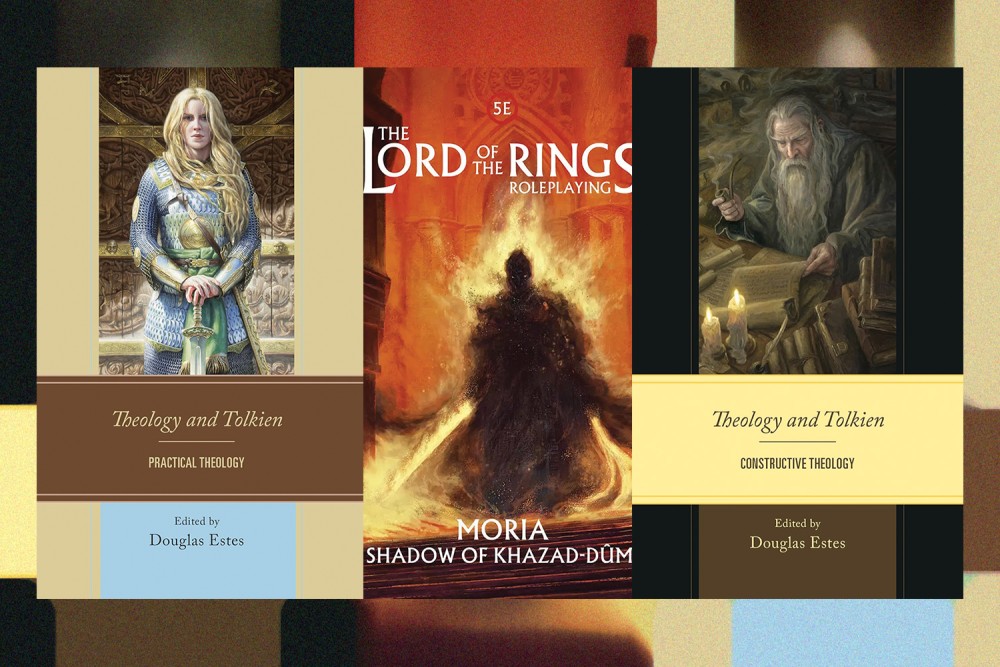

This explosion of new Tolkien-related material represents one aspect of Tolkien 2.0: the broadening artistic creation within Tolkien’s universe. But just as significant, and perhaps even more profound, is the growing academic and theological engagement with Tolkien’s works. In 2023 and 2024, the two-volume Theology and Tolkien joined the ranks of deeply rigorous, beautifully crafted scholarly collections—in this case, focused on exploring Tolkien’s religious underpinnings.

These two volumes, edited by biblical scholar Douglas Estes, offer a scholarly yet accessible exploration of Tolkien’s deep theological imagination. But they are not just valuable for their content—they are also a joy to hold. The first volume, Practical Theology, features a breathtaking cover illustration of Éowyn before the doors of Meduseld, while the second, Constructive Theology, showcases the Scrolls of Isildur. There’s a tactile pleasure in the way these books invite the reader into Tolkien’s world, with their thick and textured pages, exquisite cover art by Matthew Stewart, and solid heft. This attention to the quality of production resonates with the theological insights of the essays, all of which lovingly engage Tolkien as, in the words of Estes, a “true, unfeigned” mythology.

Tolkien’s work has long been celebrated for its spiritual and moral depth, but Tolkien 2.0 is about more than just reviving his literary legacy. It’s about a reengagement with the mythic and theological themes that he embedded in his stories. Estes sees this as both a religious opportunity and a scholarly task. In his introduction to the second volume, he writes, “We must build the scaffolding to peer over the edge of the wall between our world and Middle-earth and into the truth that Tolkien has so carefully embedded within his fairy-story, intently using ‘a distinctive form of Christian theology that does not separate heavenly concerns from worldly ones.’”

Tolkien literally made a successful bid to create a cosmology among the cosmologies, so his work demands expansive, rigorous attention. In their essay, “Theodicies in The Lord of the Rings,” Rodrigo Follis, Fábio Augusto Darius, and Ismael Silva put it this way: “Tolkien not only left us a legacy, but a universe.”

As I explored Theology and Tolkien, I was struck by the sheer diversity of scholars approaching Tolkien’s works from theological, philosophical, and literary perspectives. The collection presents a fellowship of scholars who, like the Fellowship of the Ring itself, came together from across the globe to engage deeply with Tolkien’s universe. In an interview with Estes, I half-jokingly asked if he had already formed such a fellowship before curating the book. He shared that although the fellowship did not preexist, he was amazed by the number of serious academic submissions he received.

Estes initially pursued the idea of collecting essays on Tolkien and theology after reflecting on what he wanted to do in his life. He explained to me, “We all have various times in our lives where we step back and we say, hey, what would we like to do before we pass from God’s green earth, right?” Tolkien’s works had always been important to him, and in the 2010s he noticed “an increased interest among theologians and Bible scholars for fantasy and science fiction and culture,” something that hadn’t been as prominent in earlier decades. This growing scholarly engagement with genre fiction presented an opportunity for him to connect his love of Tolkien with broader conversations on theology and culture.

Estes conducted an open call for essays, and within two months he received more than 80 abstract submissions. With the opportunity to winnow that set of proposals down to a smaller set of essays, he was free to establish rigorous standards for the project. Estes felt that much of the theology related to Tolkien was too “lay level” and lacked serious theological depth. He was also concerned that Tolkien scholarship, while important, does not have the same level of attention or output as many other areas of academic study. To address these issues, Theology and Tolkien models a scholarly approach to appreciating and engaging with Tolkien. Each essay is robustly footnoted and provides its own (often lengthy) bibliography.

For many theologians, engaging with Tolkien is a deeply personal act—like returning home, a place of comfort and exploration. Ben Riggs, (author of Slaying the Dragon: A Secret History of Dungeons and Dragons) told me in an interview that Tolkien’s creation of Middle-earth was an act of generating “a modern myth” that helps us make sense of the world around us. This mythmaking is one of the reasons Tolkien’s work continues to resonate deeply with those engaged in theology and philosophy. As Miguel Benitez Jr. writes in the first volume, reflecting on the peculiar value of Tolkien as a new myth among the myths: “For Tolkien, myths expressed far greater truths than did historical facts or events. Sanctifying myths, inspired by grace, served as a way for people to recall encounters with transcendence that had helped to order their souls and their society.”

But myths can be elusive. After examining Tolkien’s letters, Faramir’s doxology in The Lord of the Rings, and the creation accounts in The Silmarillion and legendarium, Estes concludes: “The reason so many readers experience the divine when reading The Lord of the Rings—even though God is never mentioned—is because Tolkien’s theological tendencies are apophatic.”

This presents an interesting challenge for the contributors to Theology and Tolkien, because the best theology produced on the subject doesn’t allow the mythology and poetry to fade to the background but rather helps it to shine as the basis for excellent theological reflection. As Estes argues, the goal is not to impose Christian interpretations on Tolkien’s work but to read it, absorb it, and live it out:

Whereas the allegory explicitly tells the reader, “Notice me,” the fairy story implicitly tells the reader, “Just enjoy the read,” while all the while the story is working on the reader on an imaginative level. Once read, the allegory requires the reader to transpose themselves into the text, but the fairy story encourages the reader to absorb the goodness of what comes through the text. As Tolkien essentially notes, absorption is a better mode for growth than transposition. When we read Tolkien, we absorb ideas about the way the world should be, and we seek to apply them to our world.

When approached with an eye toward absorption and applicability rather than allegory, Tolkien’s works prove to be a rich source for theological exploration that is as much about enacted imagination as it is about reflection.

This spirit of absorption and application extends beyond theology and into creativity, particularly in the realms of film and television. It’s clear that Tolkien’s works are not just texts to be analyzed but worlds to be inhabited and brought to life through various media. In recent adaptations, including Amazon’s television series The Rings of Power and Kenji Kamiyama’s The War of the Rohirrim, we see a renewed engagement with Middle-earth that seeks to expand its scope while remaining true to the heart of Tolkien’s vision.

The question has arisen in some quarters: Why do we keep returning to Tolkien’s world when so many new voices in fantasy literature are emerging, offering diverse perspectives and experiences? Part of the answer lies in Tolkien’s ability to create a world that speaks to the deepest human longings for meaning, justice, and transcendence. Though Tolkien himself was a product of his time—a White man with a cultural and philosophical outlook informed by his surroundings—his works have transcended their origins, drawing in scholars, creatives, and fans from diverse backgrounds who find universal truths in his storytelling. This fact is exemplified in the diversity of scholarly voices represented in the two volumes of Theology and Tolkien.

In a sense, the proof is in the use. Much like the myriad novels inspired by Homer, new works based in Middle-earth mythology are being produced by authors of various sexual orientations, gender identities, and racial backgrounds. These authors are also finding resources for broader representation in Tolkien’s original texts. This is likely at least in part, as Jonathan Poletti points out in a recent essay, because Tolkien’s writings “read as very ‘queer’ by the standards of the time.” Not all cultural productions of Tolkien’s era are so capacious, but Middle-earth is. In a 1968 interview with the BBC, Poletti notes, “When Tolkien wanted to speak to the spirituality of his work, he quoted a bisexual French feminist atheist” (Simone de Beauvoir).

Recent adaptations have also expanded the diversity of Tolkien’s universe, particularly in The Rings of Power, in which Amazon has worked to broaden the representation of gender and ethnicity through casting. And The War of the Rohirrim, a prequel story to The Lord of the Rings, is told in anime, a distinctly Japanese idiom. In a six-minute documentary on the making of the movie (a two-hour film that is entirely hand-drawn), comic artists speak of their pride in translating the stories of Tolkien into their Japanese storytelling style. While Tolkien’s original works were largely shaped by his Anglo-Saxon and Nordic influences, these adaptations reflect a world where Middle-earth becomes more inclusive without losing the essence of Tolkien’s storytelling. This engagement with Tolkien’s legacy in modern media not only broadens the scope of representation but also provides new ways for fans and theologians alike to engage with the moral and ethical questions that Tolkien’s world raises—and to see themselves in it.

Tolkien’s influence in popular culture extends beyond screen adaptations. In the world of gaming, his mythos has inspired entire genres of role-playing games. Tolkien believed that fairy stories invite readers to absorb moral truths through immersive engagement, and as Riggs elaborated in our interview, Tolkien’s work is not merely about fantasy or escapism but also about acting in real time to bring order out of chaos—a theme that resonates deeply in contemporary society. Riggs noted, “The destruction of the rings and the transition from the Third Age to the Fourth Age marks a new era. It’s a myth of disorder managed,” and thus it’s a fitting narrative for our time.

At the risk of thoroughly outing my own fan-ishness, I’ll share a story from a recent session I led role-playing in Middle-earth. In 2023, I backed a new Free League Kickstarter for The Lord of the Rings Roleplaying 5E game. Moria: Shadow of Khazad-dûm is a supplement for play in Middle-earth, set in the years prior to the famed doomed expedition of Balin (recounted in The Lord of the Rings). It is a 225-page volume describing the mines of Moria (the famed realm of the dwarves depicted most recently in The Rings of Power).

When I publicized (in our regional RPG Discord group) an opportunity for players to join a table and play in Moria, I was overwhelmed with the response, easily filling the table with a dozen gamers. Many of them immediately began messaging me to ask questions as they created their characters. Here’s one sample exchange:

Kevin: Ok, need language suggestions. Ranger currently knows orc, goblin, giant. What two others would a dwarf ranger of the Misty Mountains know? Maybe even an ancient human tongue? The language of the Númenóreans?

Clint: Entish? Rohirric? Underworld runes? Black speech? Warg?

Kevin: Those are all great choices.

A fan of Middle-earth will find this exchange entirely relatable. Someone unfamiliar with the works of Tolkien will find it as mystifying as if two biblical scholars had initiated a conversation in their presence on the different portrayals of the history of Israel as depicted in Chronicles versus Samuel and Kings.

However, what anyone might be able to pick up on is the sense of shared play exemplified in all of these new ways of reading Tolkien. Television and movie producers play in Tolkien’s universe through their new artistic creations. Theologians now play in Tolkien’s universe through a mixture of academic rigor and faithful, earnest engagement. Gamers play in Tolkien’s universe in the most literal sense, creating art or discovering theology on the fly through role-playing.

As we enter this new era of Tolkien 2.0, the vastness of Tolkien’s theological and philosophical universe continues to unfold in fascinating ways, and Theology and Tolkien points the way. Beth Stovell’s exploration of light and darkness, particularly through Galadriel’s phial of the star of Eärendil and its protection of Frodo and Sam in Shelob’s lair, mirrors the luminous role of Galadriel in The Rings of Power as a beacon of hope. Lisa Coutras’s essay connecting Galadriel to both the Marian archetype and the Valkyrie figure deepens our understanding of her as a powerful spiritual and mythic symbol. Who wouldn’t be intrigued by Trygve Johnson’s essay “Thinking Like an Ent: Treebeard and the Pastoral Wisdom of Eugene Peterson,” in which Tolkien’s Entish wisdom is aligned with the contemplative nature of modern Christian thought and its commitment to place? The theological theme of death and immortality, which Tolkien considered central to his legendarium, finds new resonance in “The Doom of Elves and Men,” a thought experiment in which Keith Mathison connects the biblical myth of Adam with Tolkien’s hypothetical case of immortal Elves and mortal Men, offering profound reflections on the nature of human existence and the limits of immortality.

Another essay dives into olfaction and Hans Urs von Balthasar’s claim that “only they can see, hear, touch, taste, and smell Christ whose spiritual senses are alive.” Here, Trevor Williams shows how the sense of smell in Tolkien’s world—whether in the Nazgûl’s attempts to catch an elusive scent or the fragrant, sanctifying essence of the Shire—becomes an avenue for discovering the Divine. In a similar vein, Chris Bruno and Mark Brians’s essay argues that Tolkien’s work is inherently Hobbit-centric, focusing on the sanctification of the humble and the everyday, with Frodo and Sam’s journey symbolizing the transformation of the ordinary into the extraordinary. In his own essay, Estes reinterprets Gandalf’s role in Tolkien’s world, viewing him not as a Christ figure but as an apostolic figure, a messenger of wisdom and guidance who helps others find their way through darkness into light.

Every essay in these two volumes is meticulously crafted, and together they showcase the depth of Tolkien’s legacy as a theological and literary treasure trove—one that continues to inspire new generations of scholars to play in his universe in ways similar to cinematographers and gamers. Tolkien 2.0 is not merely an academic endeavor; it is a living, breathing exploration of how his works can speak to the present. As we journey deeper into Tolkien’s world, we are reminded that his mythos is as expansive and transformative as the very light that Galadriel carries in her phial—a light that can still guide us in our own age of shadow.