Doubting Thomases in an age of science

It takes courage to plunge our hands smack-dab into the side of the universe and reach for a God that could be real.

Photo: Taylor Smith on Unsplash

Thomas is my favorite apostle. I gotta love a guy who, regardless of the niceties of the situation, when offered the opportunity will thrust his hand smack-dab into the side of the risen Lord because he needs to experience a God who is real.

I’m certainly a big believer in doubt, which qualifies me as both a progressive Christian and a conventionally faithful one. But I don’t think doubt adequately describes Thomas’s problem, nor does reassurance adequately describe his solution. Doubt is cerebral (Did I remember to turn the stove off? Is her house on the left or on the right? Do these pants make me look fat?). And seeing in order to believe is primarily concerned with confirming something exterior or posterior, as the case may be. What my favorite apostle seems to me to be asking for, however, is a more visceral experience.

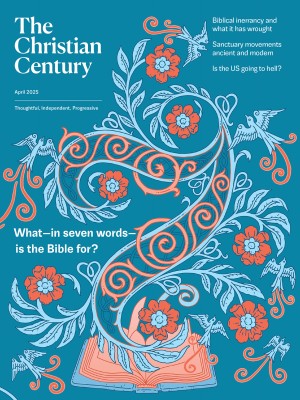

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Thomas reaches his hand into the side of Jesus’ body because he needs to know in his own body that this God is real. Because if Jesus has truly been resurrected, then Jesus is God, and if Jesus is God alive again and right here, in his body, in this upper room, then Thomas can trust that the devilish work of empire—all the lies, the violence, the ignorance, the demagoguery, the death, and the subterfuge—even if it lasts ’til the end of time, even if it vanquishes him, will not win. And this is exactly the sort of fierce hope we all need this year, not just intellectually but in our bones and muscles, so that we have the energy to get up and get on with doing the work of proclaiming the gospel (or saving the world, for Pete’s sake) in a bleak time. But first of all, we need to believe that this God and this resurrection are for real.

I’ve been reading a book by scientist, historian, and former atheist Nancy Abrams, called A God That Could Be Real: Spirituality, Science, and the Future of Our Planet. Abrams is married to astrophysicist Joel Primack, who was instrumental in quantifying dark matter and theorizing something illegible called the double dark universe. Abrams and Primack are experts in the sort of science that is impossible to visualize, inspires highly visible Marvel movies, and is irrelevant to our daily lives but is nonetheless, astonishingly, true.

Abrams is also a professor and a successful writer. But, she writes, she has a problem. She has an eating disorder and is living in hell. Having tried pretty much everything else, she finally enters a 12-step program and, to her amazement, begins to get better. She is, however, stymied by step three: “We made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.”

Wisely disregarding the insult of the male pronoun, she rationalizes that since it obviously doesn’t matter to her 12-step group how she defines her higher power (as long as she identifies one), she will turn her life over to her own highest self—her aspirational self, as she calls it, something intensely real for her. It works. For a while. But eventually, for no reason she can understand, she starts to sabotage herself. When her best self is the locus of power, there is nothing larger than herself, nothing more dependable than herself, nothing able to love her more than she can love herself, nothing outside the authority of her own mind to turn herself over to. She backslides. She is back in hell.

After floundering for a while, she begins the long process of trying to define for herself a God that could be real, that exists independently from her own mind and does not conflict with the precepts of modern science and quantum mechanics, which are her bedrock beliefs. While Christians would not recognize her understanding of this God as biblical, it is marvelous, it is awesome, and it is real for her.

God, she writes, is our co-creation. This God could not have come out of nothing but was born from and for the people of this earth, although we do not control her. God evolves as we evolve but over countless centuries has accrued independence and agency apart from us, fed by human aspirations as uncountable as Abraham’s stars. This God is like (I am at a lecture of hers now and she is struggling for the right image) “an African termite mound: still growing, toweringly tall, 90 feet wide and 3,820 years old, built over centuries by a slew of three-millimeter blind termites.” In her analogy, God is the living edifice. The blind termites would be us.

Her passion, her anguish, her struggle, however, remind me of no one more than Thomas, thrusting his hand into the side of the living God. It took courage for Abrams to reach beyond the God of her childhood and to reach through walls that since the Enlightenment have separated science from religion. It took courage to plunge her hand smack-dab into the side of the universe and reach for a God that could be real.

I think it was a similar longing that compelled thousands of people across this country to hop in cars, buckle up on airplanes, and travel vast distances a year ago to stand outside on April 8, 2024, and stare up into the burning underbelly of God. OK, call it the sun. But it was more than the sun. It was the absence of the sun (a miracle) and the return of the sun (another miracle). That is what our bodies registered, even if our minds had it cognitively under control.

What drew us? What longing? A longing, perhaps to feel simultaneously dwarfed and ennobled by something enormous that was not us. And we knew this higher power was real, because without our special glasses on, she would have burned our eyes out.

After the eclipse, people had a hard time finding words for their experience, often describing it in quasi-religious terms. It was . . . I dunno . . . cosmic, one person said. It was the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen, his wife breathed. In a post-Enlightenment world of ever more particular partialities, we long for a totality. Sick of ever-fracturing divisions, what a blessing it was, last year, to turn in the same direction and look up and behold.

I know two people who drove to Austin, Texas, to see this miracle, and a woman who flew to California, and a priest couple who went all the way to Mexico to be assured of clear skies. I ended up in a cabin in the remote woods of the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont with a friend from childhood, now a Sufi, who I hadn’t seen in 20 years, and her friend, who is part Native American. We sang. We saged. We tromped in circles. It was perfect.

It helped that it was limited. We only had to give up control of the planet for three and a half minutes. I tried to take a photo, but my iPhone immediately corrected the image, which destroyed it.

There are 54 more years until the next totality in my neighborhood. If I’m not dead by then, I’ll have some explaining to do. Which reminds me of why, in spite of everything—small, puny, grateful, social, awestruck termite that I am—I go to church. Together we turn to face the altar. As a people we look up. “Peace be with you,” someone says. And then we go home.

Last spring’s moment of planetary togetherness seems almost quaint now, looking back on it as we face ever more intractable divisions, many purposefully manipulated by a newly empowered demagogue. Reality appears to waver like a mirage on a highway or a faulty TV signal. But for a moment last April we stood together, on our individual mountaintops, equally dwarfed by what was happening overhead. It was a moment of unity, simultaneity, humility, and awe. Like Thomas, we plunged our hands up to the elbows and experienced the real.