I still have a voice

After the election, I was worried about people being silenced. So I joined a choir.

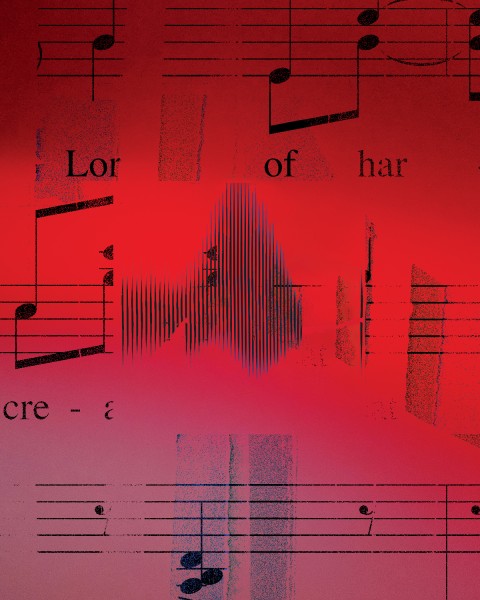

Century illustration

The morning after last fall’s election I awoke from a dream in tears. In the dream my voice was gradually diminishing, and soon people couldn’t hear what I was saying. I attempted to amplify my voice, but it became thinner and wispier until finally it made no sound at all. I grew increasingly frustrated, angry, and scared until I awoke, heard my own sobs, and realized that I still had a voice.

In the dream, the loss of my voice was not a metaphor; it was a physical phenomenon that I could almost feel. But in that waking moment, I was left to interpret it metaphorically and to make sense of the wisdom of the dream. It felt like foreshadowing. I’d gone to bed worried about all those who stand to lose their political voices in the coming years, worried about women’s voices and Native voices being further diminished, silenced, and ignored.

Thankfully, I have places where I’m able to use my voice. I teach, preach, advocate, educate, and write for publication. But that morning I thought about my voice at a more literal level. I do not have a particularly strong voice for a public speaker, and I’ve never been trained in vocal techniques. I usually need good amplification. I speak slowly and distinctly, but my voice sounds thinner as I age. I found myself longing not just to speak and share conversation but to sing—to sing with others, to blend voices and harmonize. This desire as a response to the dream came as quite a surprise.