Jimmy Carter, America’s best ex-president

After his 1980 defeat, Carter devoted himself to the causes of a progressive evangelicalism that has all but disappeared from public view.

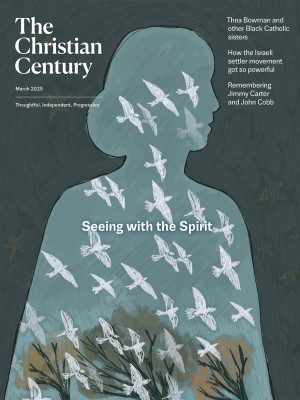

Former president Jimmy Carter, 1924–2024 (US Navy photo / Timothy A. Hazel)

Jimmy Carter, the 39th president of the United States and the oldest surviving president in American history, died December 29. By any reckoning, he led a remarkable life.

Anyone who visits Plains, in southwest Georgia, and especially the Carter farmstead three miles down the road in Archery, cannot fail to be impressed by the simplicity of Carter’s background. Carter himself never complained about the circumstances of his childhood, and in fact he often made the point that his family was more prosperous than their neighbors. But the Carter farmhouse lacked indoor plumbing during Jimmy Carter’s childhood, and it wasn’t until he was 14 years old that Franklin Roosevelt’s Rural Electrification Agency brought the wonders of electricity to Archery.

Carter walked three miles to school and back, often barefoot. He was acutely conscious of his status as a “country boy,” but he studied hard and read diligently. His favorite teacher, Julia Coleman, often remarked that one of her students might become president of the United States someday. Carter was listening.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

After graduating from Plains High School, Carter attended the U. S. Naval Academy and, upon graduation, was commissioned as an ensign. Together with his new wife, the former Rosalynn Smith, he embarked on a career in the navy.

In 1953, however, Carter was summoned back to Plains. His father, known in the community as “Mr. Earl,” was dying. As Carter stood at his father’s bedside, he listened as countless members of the community came to pay their respects and to thank Mr. Earl for small acts of kindness: extending credit from the Carter store, carrying their mortgage in times of financial stringency, providing new clothes for a poor family so they could attend their daughter’s graduation with pride.

When Carter returned to Schenectady, New York, where his young family was stationed at the time, he informed Rosalynn that he was resigning his commission to return to Plains to try to have the kind of influence on the community that his father had. Rosalynn, who enjoyed her status as a navy wife, was not amused. Apparently, the automobile trip from Schenectady to Plains transpired in almost total silence between these two strong-willed individuals.

The rest is history: the Georgia state senate, governor of Georgia, then the improbable run for president of the United States. Carter was assisted every step of the way by Rosalynn, his wife for 77 years until her death in 2023.

I believe it is impossible to imagine Jimmy Carter becoming president had it not been for Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. Johnson had lied to us about Vietnam; Nixon had lied about, well, pretty much everything. We needed to know that our president had a moral compass, and Carter, a Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher, arrived on the scene and promised that he would never knowingly lie to the American people.

We elected him president in 1976. The country was in a mess when Carter took office in 1977: the lingering scars of the Vietnam War, Watergate, the Arab Oil Embargo, runaway inflation and soaring interest rates.

Carter’s presidency is not generally considered a successful one, and I would be hard pressed to argue otherwise. But historians have a way of revisiting the past, and now, more than four decades since Carter left the White House, they are beginning to appreciate many of his accomplishments: the Camp David Accords, the renegotiation of the Panama Canal treaty, his emphasis on human rights, his calls for energy independence. Carter appointed more women and minorities to office than any president before him, and many conservationists consider him the best environmental president ever.

Carter’s devastating loss in his 1980 bid for a second term might have persuaded a lesser person to retire quietly to Plains. But Carter had other ideas. The Carter Center, founded in 1982, has compiled a remarkable record of averting military conflicts and eradicating disease. As Carter conceded in one of our conversations, he very likely would not have done any of these things had he been elected to a second term.

I first met Jimmy Carter at a small gathering prior to an academic conference at Emory University. What he wanted to talk about was what he characterized as the “unsurpassed joy” of telling others about Jesus. He was referring, of course, to his own religious transformation, which occurred in 1967, shortly after he lost his first campaign for governor. Carter was disconsolate. He had campaigned so vigorously that he lost 22 pounds, and he had invested a great deal of money into the effort. Worse, he had lost to Lester G. Maddox, of all people—a notorious segregationist who rose to prominence when he confronted three Black men with an ax handle as they tried to integrate his restaurant the day after Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

When Carter returned to Plains after his bitter defeat in the 1966 election, he began searching his soul. With the help of his sister Ruth Carter Stapleton, a Pentecostal evangelist, Carter rededicated his life to Christ. Shortly thereafter, he headed to Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, with other Southern Baptist laymen to knock on doors and share their faith. Later that same year, Carter was paired with a Puerto Rican minister for a similar venture in Springfield, Massachusetts. Carter, with his rudimentary command of Spanish, would read from the Bible in Spanish-speaking neighborhoods, and the pastor, Eloy Cruz, would preach. At the end of their week together, Carter pressed Cruz about why he was so successful. Cruz demurred, thinking that Carter was superior to him. But Carter insisted.

“Señor Jimmy,” Cruz finally responded, “the secret to faith is to have two loves: one for God and the other for whoever happens to be standing in front of you at any given time.”

Carter sought to live and to govern according to that principle. Not perfectly, of course; none of us is perfect. His policies were remarkably consistent with those articulated by the 1973 Chicago Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern, which in turn mirrored the priorities of 19th-century evangelicalism: concern for minorities, helping the poor, and equal rights for women.

Arguably the greatest political paradox of the past century is that evangelicals, the very voters who helped propel Carter to the presidency in 1976, turned dramatically against one of their own to embrace Ronald Reagan four years later. Religious right leaders concocted a high-minded reason for their defection: opposition to abortion. But this is utter fiction. (Carter, in fact, had a much longer and more consistent record of opposing abortion than did Reagan, who as governor of California had signed into law the most liberal abortion bill in the nation.) These evangelical leaders, led by Jerry Falwell and organized by Paul Weyrich, mobilized instead to defend tax exemptions at segregation academies and at such places as Bob Jones University. Reagan adroitly seized on the issue.“I know this group can’t endorse me,” he famously said to an evangelical audience in August 1980, pausing for effect, “but I want you to know that I endorse you and what you’re doing.”

That speech made no mention of abortion. The 1980 election nevertheless marked the beginning of an alliance between the religious right and the Republican Party, one that has calcified in the years since. Tragically, Jimmy Carter’s progressive evangelicalism—a term he embraced during my final interview with him—has all but disappeared from public view.

My favorite quote about Carter came from James Laney, the former president of Emory University. “Jimmy Carter is the only person in history,” Laney said, “for whom the presidency was a steppingstone.”

Carter hated that quote, but he is generally regarded as the best ex-president in American history. And now that the partisan gloss his political adversaries had painted has begun to fade, historians are coming around to view his presidency more favorably.

History, I suspect, will treat him the way he typically treated others: gently, and with kindness.