After every election, I turn to Tolstoy

His challenges to the left and right alike are devastating and timely.

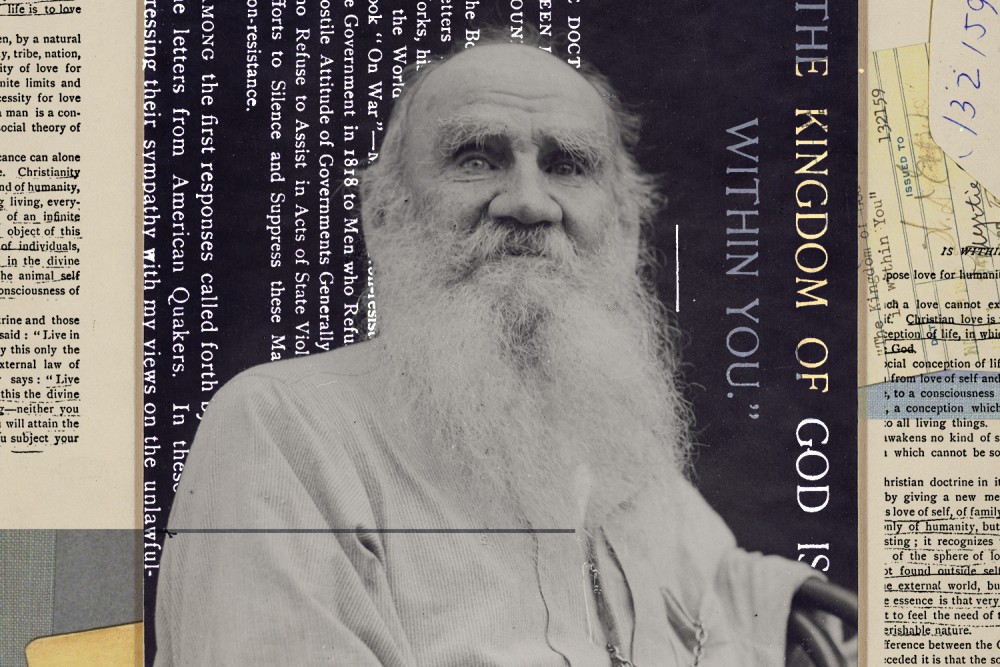

Leo Tolstoy (Vladimir Chertkov / Creative Commons)

Occasionally one of my children will ask me, “Am I your favorite child?” This both elicits a laugh I don’t think they were going for (and can’t be good for their confidence; I should work on that) and musters up this strange competition between them, a jockeying for my approval. This is not unique behavior within the animal kingdom, nor is it exclusive to youth. As a sibling I know it well. There’s something about being affiliated, being deemed good by someone else, and being on the right side of favor that stirs up something within us that seems to be in perpetual need of stirring. We choose teams. We pick sides.

And when I explain to my two children that neither one of them is my favorite, there is a look that they never need to put into words, because I am a pastor and I know that look. The look is disappointment. The last time I saw it in my congregation was before the election. I was insisting that we were going to hold our peace, do the work of love, and be the church no matter who won. People seemed disappointed—some said they were, actually—because I didn’t “come out” for someone.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The legal realities of nonprofit organizations aside, you wouldn’t need to listen to me talk for five minutes to know my politics, my hope for the world, and who I most definitely voted for. You would also learn that the most influential book on my political theology is Leo Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You, which once read cannot be unread. I return to it after every election season. Its reminders to the left and right are devastating and timely.

The book, written not long after Tolstoy’s “conversion”—he was baptized Christian but, like a lot of people, didn’t take it seriously until late in adulthood—is an essay or missive or series of rambling thoughts about the dangers of the relationship between the church (in this case, Russian Orthodox) and state (the Russian Empire). Tolstoy, absolutely mesmerized by Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, basically thinks that the ethical content of this sermon is the only thing worth pursuing—he cares nothing for the spiritual content—and that by its very nature the state can never live into the mandate Jesus presents there. Therefore, the state is useless, and the church commits a great hypocrisy in even attempting to align with it.

Tolstoy is known as one of the great Christian anarchists, but he was far from the first or most articulate. What is remarkable, however, is that perhaps the world’s foremost writer at the time (see War and Peace), while experiencing the pain and suffering of a midlife crisis (perhaps from writing 1,000 pages of War and Peace), was willing to stake his life and his membership in the nobility to say to church and state, “Neither of you.” He was swiftly excommunicated for saying something that needed and needs to be heard: Maybe we should focus on following . . . Jesus?

Nowadays when you hear something like that, it’s usually from a pastor who doesn’t want to touch politics at all. But Tolstoy doesn’t say that, nor does Jesus (who is killed for sedition against the state, by the way). They advocate not for a life absent from the political sphere but for one less dependent on what happens there.

You’ve witnessed and participated in the arguments and felt them deep in your body—the tensions, the nervousness. I’ve had church members come to my office because they felt existentially altered by the election results. And to be sure, those fears are well placed. Millions of voters have provided what seems to be a mandate to change the world as we know it, and life will therefore be harder and more dangerous for certain people our emerging government has promised to neglect.

But when I see pastors crying doom and fearmongering—as distinct from pushing us to change our church processes to help protect people—I sense an expression of something not entirely Christian. I, like many of them, had a horse in this race. I also know that if the question is which candidate is going to fulfill Jesus’ mandate to love and forgive and humanize, the answer is pretty clear: “Neither of you.”

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t vote—we absolutely should—but when it comes to what’s at stake, or whether you “won,” I think we’re giving the state too much credit. It is a broken institution, this empire, and as a Black man I have come to trust its brokenness almost like clockwork. So for me, placing even a sliver of my spirit into this realm is a fool’s game—or worse, idolatry.

I can understand how people who have felt less of the state’s violence might have a greater sense of wellness correlated with the health of the state. I can even understand my ancestors, who experienced state violence far worse than I ever will, advocating for deep civic participation as the key to enlivening the beloved community. I appreciate this sentiment even as my generation wrestles with the beautiful hope and naïveté of its premise.

But what I don’t hear enough—and what gets me so many looks when I say it myself—is that this dark moment in our nation’s history is not going to determine whether we as a people are well or not. Our spirits will not be tied to this mess or the xenophobia that has caused it, because whoever wins an election, we the believers in love and justice still have work to do, people to hold to account, relationships to build. The difference is whose office we will call and how loud we will have to yell.

If this tumultuous aftermath can in any way make us OK or not OK at the core level of our being, then we’ve invested too much. I hear Jesus say this. I hear Tolstoy say it. But I don’t hear it enough in faith communities. And that makes me ask what gods we really serve.