September 15, Ordinary 24B (James 3:1–12)

As a preacher, I used to worry that people don’t listen to me. Now I worry that they do.

I am a manuscript preacher. I learned very early that if I speak extemporaneously about anything important, I’ll spend the next 72 hours trying to remember what I said. Sometimes with anxiety, convinced I said too much. Sometimes with frustration, convinced I left out something vital. But with my trusty manuscript, I can review and perseverate in peace. Because I know that, for better or worse, that’s exactly what I said.

I used to wonder whether anyone heard me when I preached. All those still, sober faces, looking at me as if nothing at all remarkable or interesting were happening. Thinking about what came before, what comes next, fully occupied in their reverie. It took some time for my ego to recalibrate.

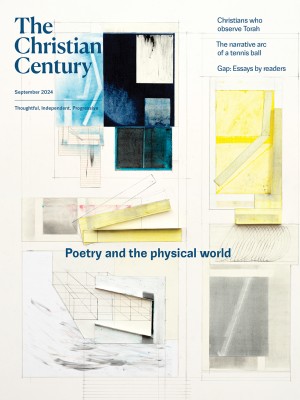

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Now, all these years in, I worry that people do listen to me. That they treat my words as worth paying attention to, taking notes in agreement or as fodder for future arguments. While we Mennonites don’t have a high view of the clerical voice, I still worry about the power inherent in the pulpit. I worry about my words being taken too seriously.

James is right: “Not many of you should become teachers, my brothers and sisters, for you know that we who teach will be judged with greater strictness.” That sounds like the voice of experience. If so, I would love to know what that experience was. Did James say the wrong thing to the wrong person at the wrong time? Was it a personal mistake requiring an apology? Or was it a less than orthodox take on a pressing problem of the day, resulting in a summons from the elders?

Whatever the prompting, James goes on one of those rhetorical rolls some of us preachers can’t resist. The hits just keep on coming as James works to overwhelm any potential resistance. I’m tempted to say his tongue gets away from him, but I’m sure James is intentionally overdoing it. James piles on the images, and all of it intended to warn against letting one’s mouth go ungoverned by one’s better angels. James makes the case that an unbridled tongue, like the unbridled ego that mismanages it, is indeed the source of much woe.

Early in my preaching ministry I made a mistake that has stuck with me. I’d like to say it was a slip of the tongue, but my pesky manuscript tells me otherwise. During a sermon, I said something snarky about a local Christian radio station. About how the Mennonite bishops back in the day were right when they banned it. Their intention was to diminish the impact of fundamentalist preachers on good Anabaptist folk. My intention was to be clever. I still think the bishops were right. But I was not.

Later that week I got an email from one of our members. She told me how demeaned she felt by my comment. How the radio station played the kind of music she found comforting. That music, she said, made her day better. I apologized. And I learned something important to my future preaching.

The admonition James offers demands attention. As a preacher, it is vital that I not only watch what I say but also remember who I am saying it to. Like many congregations, mine contains a mix of worldviews, politics, and theologies. I cannot assume that everyone shares my perspective on the text and the world. This sometimes makes preaching feel like walking a tightrope. It can also lead to timid sermons that are so vague and generic they miss all the marks.

Of course, James does not argue that no one should accept the teaching-preaching role. He simply calls those of us who choose to accept it to remember that there is a lot at stake. The standard is high, as is the risk of bringing judgment down on our heads.

It is no small thing to be called to speak into the lives of others and to do so from the pulpit. Even we low-church preachers need to be wary of ignoring and so misusing the power that comes with the role. People are listening. Wisely or not, our words are treated with respect and attention. It’s the kind of realization that can keep me up at night.

Our mouths do need to be managed. They need a bridle and someone at the reins if they are to serve without causing harm. Spiritual directors, preaching workshops, and therapy can assist us in managing our tongues. In my case, the sermon script serves as that bridle. Something about seeing the words on the page reins me in. Most of the time.

As James acknowledges, I still make mistakes. We all do. But with James in mind we can do better next time. At least that’s what my manuscript says.