Amos Brown, pastor to Kamala Harris, known for civil rights, reparations activism

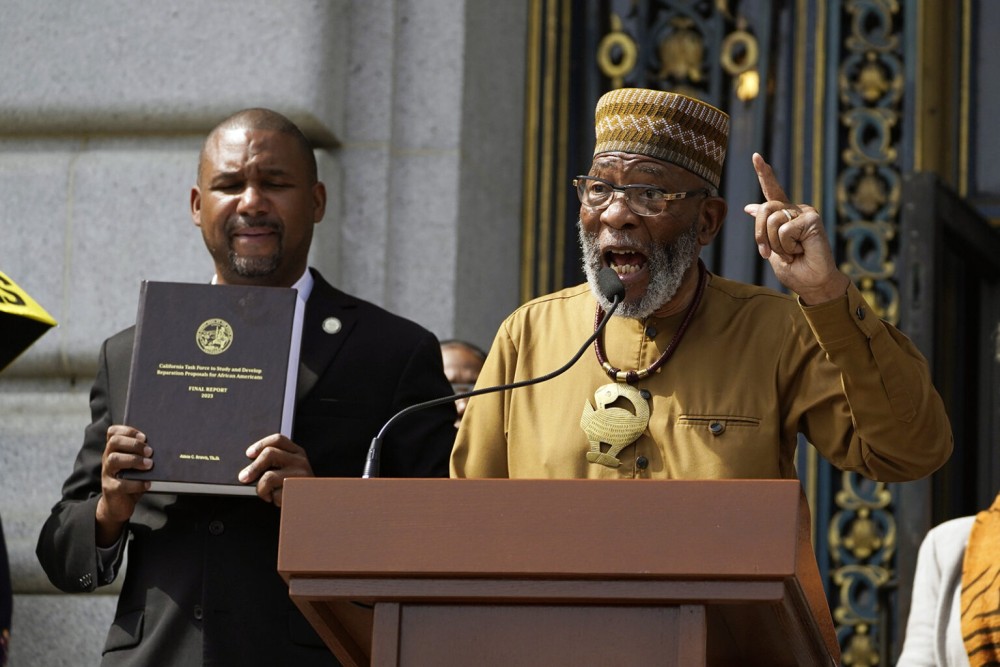

Amos Brown speaks during a rally in support of reparations for Black Americans as Supervisor Shamman Walton, left, listens outside City Hall in San Francisco, on September 19, 2023. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg, File)

Amos Brown, a longtime pastor of Third Baptist Church of San Francisco, was specific when he described Vice President Kamala Harris’s connection to his church.

“She’s an old-timer” at the church, he said in an interview on Monday.

That might help explain why, when Harris met with Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Sikh leaders in Los Angeles in 2022 to discuss abortion rights and other issues, Brown was in attendance.

Or why, when she spoke of him that same year, she praised “my pastor” as a man who also has long been her mentor.

“For two decades now, at least, I have turned to you,” Harris said in remarks at the 2022 Annual Session of the National Baptist Convention, USA. “I have turned to him. And I will say that your wisdom has really guided me and grounded me during some of the most difficult times. And—and you have been a source of inspiration to me always. So thank you, Reverend Brown, for being all that you are.”

And the long-standing connection between the two might be why Harris turned to Brown again this week, reaching out to him over the phone after President Joe Biden abandoned his reelection bid and endorsed the vice president. She asked for prayer, and Brown happily obliged.

Brown and his wife prayed that Harris “would receive the thing that Micah 6:8 records in the Bible, the fulfillment of what the Lord requires: to do justice, love mercy and walk humbly with her God,” Brown said.

He also prayed Harris would move forward in her campaign “in the spirit of our ancestors.”

Brown recited lines from “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a hymn sometimes referred to as the Black national anthem: “God of our weary years, God of our silent years, Thou who hast brought us thus far on the way; Thou who hast by Thy might, Led us into the light, Keep us forever in the path, we pray.”

“That’s what this nation needs,” Brown said, later noting that he endorses Harris for president in his personal capacity. “That’s what this vice president and, hopefully, president, will be elevated to be: To bring this nation out of darkness. The darkness of incivility. The darkness of lying. The darkness of injustice. The darkness of irresponsible behavior—and that goes at all levels, from the local community up to the national government.”

Brown, 83, explained he and Harris also have a shared political history: Harris served as Brown’s campaign manager when he ran for reelection to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1999, and Brown joined his wife in praying over Harris and her husband, Doug Emhoff, immediately before the 2021 inauguration ceremony.

“She was very close to our church family,” Brown said.

Brown’s history with Harris extends to her family as well. A Jackson, Mississippi, native and civil rights activist who was taught by Martin Luther King Jr. in a class at Morehouse College in the 1960s, Brown mentioned meeting Harris’s mother, Shyamala Gopalan, along with others who participated in civil rights activism.

He formerly was a leader of Baptist churches in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and St. Paul, Minnesota, and has pastored Third Baptist since 1976.

His church, which has been affiliated with the National Baptist Convention, USA, and the American Baptist Churches USA, was the site of a 2023 meeting of California’s Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans shortly before it released its final report.

“Harm has been done to Black folks by this nation,” Brown, the vice chair of the task force, said at the time. “And it’s time for us to respond and not react but respond in a responsible, rational, realistic way that will give us results to bring Black folks from the bottom of the well economically, academically, healthwise.”

The Associated Press/Report for America reported in May that the California Senate had sent reparations proposals to the state Assembly, including a measure that would help Black families confirm that they were eligible for future state restitution.

Speaking this week, Brown attributed Third Baptist’s longevity (it was founded in 1852) to its long history of social justice advocacy—or, as he put it, “the fact that we’ve always been focused on the liberating gospel of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, and we have not focused on personalities.”

He added: “That’s why Vice President Harris, early on in her academic and political careers, connected with this church.”

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Brown was an opponent of churches reopening too soon.

“We are not going to be rushing back to church,” he said in a phone interview with the AP, noting that many denominational leaders had died or been sickened. Freedom of religion is “not the freedom to kill folks, not the freedom to put people in harm’s way. That’s insane,” he said.

In 2020, Brown was among a list of 350 faith leaders who endorsed the Biden/Harris campaign.

Early in the Trump administration, Brown supported Black clergy who declared themselves independent of both the “liberal left” and the “religious right.” He advocated for get-out-the-vote efforts ahead of the next elections when he spoke during a 2018 news conference.

“We’ve got to really vote like hell in this midterm election and in 2020 and get rid of this excuse ‘my one vote won’t count,’” said Brown. “Every vote counts. We’ve got to get that over to our congregations.”

This week, however, Brown appeared to lob thinly veiled criticism at former President Donald Trump, the 2024 Republican nominee. Referring to how versions of Christianity’s “golden rule” can be found in multiple religions, Brown asked how someone could refer to immigrants as “evil, cruel” or “rapists”—a reference to descriptions Trump has used.

“Why would you do that to other people?” Brown said.

Earlier in his tenure at Third Baptist, the church created a summer school program, a music academy and an after-school enrichment program with a local synagogue.

Beyond his church, Brown has been involved in national and global events, including the 2001 United Nations Conference on Race and Intolerance in Durban, South Africa, where he represented the NAACP’s national board.

Brown told the San Francisco Chronicle that he learned from King, “sitting at his feet at Morehouse,” about “personalism”: “Every person should be viewed as having dignity regardless of how different they may be. We should respect them.”

In what might seem to be unusual pairings, Brown has joined forces with people outside Black Baptist circles for collaborations.

In 2014, Brown and evangelist Franklin Graham wrote a joint anti-violence opinion column in USA Today in the wake of the police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York.

“None of us is always right—and none is always wrong,” they wrote. “We believe we could all use a good dose of humility—we must avoid arrogance, even in our convictions.”

Brown, president of the San Francisco branch of the NAACP, appeared at a news conference marking the 2022 rededication of the Washington, DC, temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 2021, the LDS church and NAACP launched initiatives including scholarships for Black college students.

Brown is the namesake of a fellowship that has brought young adults to Ghana with leaders of the NAACP and the LDS church to learn the history of slavery.

“I am humbled by this great example of this faith community uniting in order to heal the breaches in our nation, making bonds and setting the bar higher for us to move away from war, strife, prejudice in a world that so desperately needs people of good will and justice,” Brown said at the news conference.

Brown told the Chronicle in a 2021 interview that the LDS church’s family research enabled him to learn that his great-great-grandfather, who was born enslaved, eventually owned 150 acres of land and with two other Black men established a church and a school.

“(I)t’s a blessing to me that even in my genealogical chart there was a meeting of self-determination, of enlightened piety, social justice, and high and noble respect for education,” he told the San Francisco newspaper. —Religion News Service