Praying the hours with W. H. Auden

The poet’s Horae Canonicae sequence is an underappreciated spiritual classic.

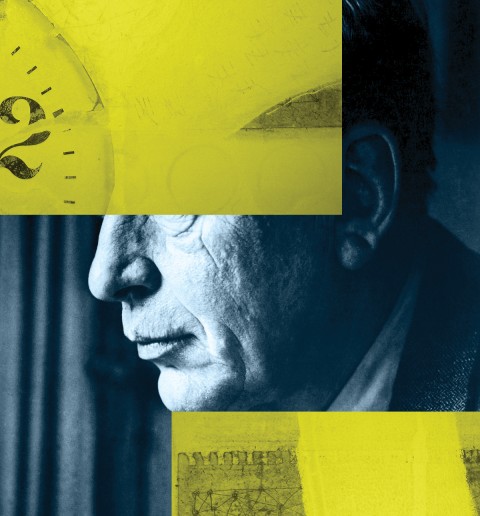

(Century illustration)

In 1955, W. H. Auden published The Shield of Achilles. The poetry collection includes a lengthy sequence of poems that I would rate high among the spiritual and devotional classics of the 20th century but which still receive nothing like the attention they deserve. I am delighted that my Baylor University colleague Alan Jacobs has produced a splendid new edition of that book (from Princeton University Press), with an invaluable introduction and scholarly commentary.

The sequence is titled Horae Canonicae, because its seven poems follow the canonical hours of the monastic day. They were originally published separately between 1949 and 1954. It’s difficult to summarize these poems, not least because they are so richly allusive and theologically suggestive: imagine trying to offer a plot summary of Eliot’s Four Quartets. Reasons of space and copyright prevent me from offering extended quotations here. I can only beg you to turn to the original text and lose yourself in Auden’s words.

Auden was drawn to Christian faith partly through his interactions with poet Charles Williams, of Inklings fame, and he began to identify publicly as a Christian in 1941. For some years he understood the faith strictly as an internal matter. Gradually, as he encountered the work of Kierkegaard and Reinhold Niebuhr, he acknowledged the need to relate faith to social life and daily interactions, all in the context of a sinful and fallen world.