Consciousness all the way down

If consciousness is universal and the universe is fine-tuned for life, Philip Goff argues, then there must be a cosmic purpose.

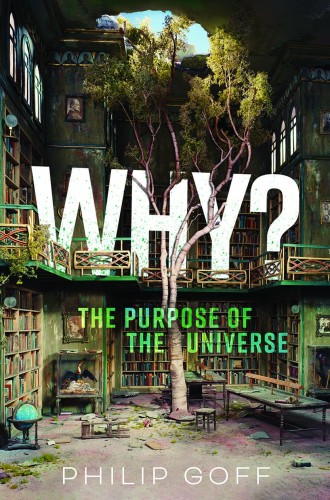

Why?

The Purpose of the Universe

Do trees have minds? A friend posed this question during one of the high school afternoons we habitually spent—no doubt with too much time on our hands—engaging in amateur philosophical banter. It struck me immediately as absurd. Minds require physical brains, I replied, as well as observable behavior that demonstrates the existence of a mind behind it. He was not convinced and responded that trees might have a type of consciousness that is different from ours.

As it turns out, there is a spirited movement afoot among some British and American philosophers, theologians, and a few neuroscientists that takes my friend’s question seriously. The figures in this movement generally hold that, for mind to exist at all, it must be a basic constituent of reality. If mind is as fundamental to reality as matter, it can be inferred that it extends beyond the complex nervous systems of human beings and higher animals and thus belongs, in an admittedly more rudimentary sense, to trees and other plants, to single-celled organisms, to natural bodies like mountains and rivers, to manufactured objects like tables and chairs, and in fact to the elementary particles—electrons, protons, neutrons, and quarks—that make up the universe. This viewpoint, known as panpsychism, declares that consciousness, in some form, goes all the way down.

For the last hundred years, the dominant position in Anglo-American philosophy when it comes to the nature of the mind has been materialism, the rather dreary assessment of our inner, conscious lives as the manifestation of nothing more than the biological functioning of our brains. In its most extreme form, this view holds that the mind, and with it the self, is an illusion, a trick that the brain plays upon us. The publication of Australian philosopher David Chalmers’s The Conscious Mind in 1996, however, brilliantly called the reigning materialism of the philosophical world into question and changed the conversation. Chalmers argues that theorists can explain “easy problems” of consciousness involving descriptions of our cognitive functioning but not the “hard problem” of why we have any inner, qualitative experience at all. Materialism cannot explain what it is like, subjectively, to be aware, to know, and to feel. Chalmers advances a position he dubs “naturalistic dualism,” according to which everything in the world has irreducible physical and mental attributes. A new generation of thinkers influenced by Chalmers has subsequently embraced panpsychism as a more compelling approach to the stubborn fact of consciousness than theories that try to explain it away.