My dad’s old Bible offers more questions than answers

What can I learn from what he underlined—or didn’t?

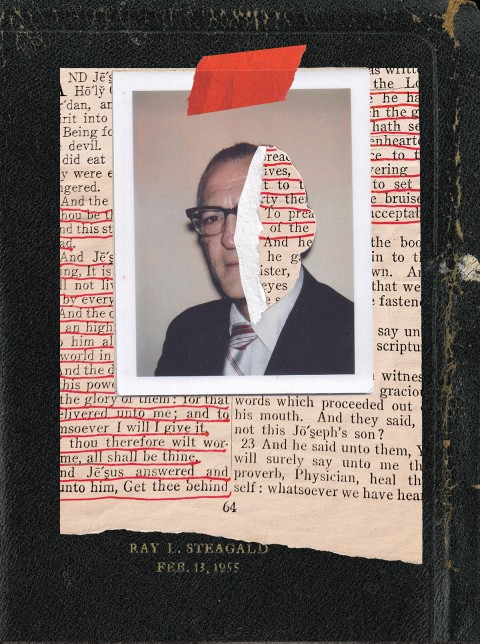

(Illustration by Vanessa Saba)

I inherited my dad’s bible, a battered old Thompson Chain-Reference (KJV), upon his death in 1988. It is an amazing storehouse of information that Frank Charles Thompson assembled in hopes of couching the scriptures in “simple yet scholarly” terms for interested and studious laypeople—as well as for struggling preachers like Dad. The genesis of Thompson’s project, in fact, was his frustration regarding the limitations of reference Bibles in his time. The result, first published in 1908, was a block of righteousness that Dad considered an indefatigable doorstop to keep closed all the gates of hell.

Each double page of sacred text is flanked and guttered with cross references (more than 100,000 in all). In the back are a concordance, thick indexes of explanatory notes, and in-depth character studies. There is a plenitude of charts and maps, not to mention the complex “chains” of Thompson’s references (more than 4,000).

Dad’s particular copy presents as a leathery, tough veteran: unyielding and strong, the kind of book you want on your side in a personal theological throw-down or in a battle in whatever war the culture might be fighting. True to the part, the book has taken some hits: it has scars, and its increasingly brittle stiffness suggest it might be time for a Purple Heart and an honorable discharge.