Too much mystery?

Leaving evangelicalism allowed me to embrace the mystery of faith. I wonder if I’ve taken it too far.

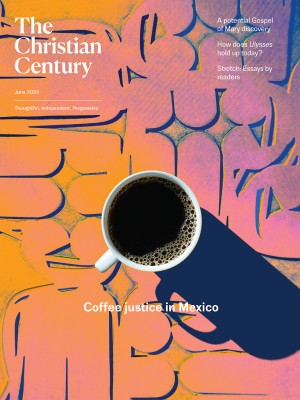

Century illustration (Arch source image by Tim Starke / iStock / Getty)

One of the greatest gifts progressive Christianity has given me is the gift of mystery. I grew up in a church tradition that put a lot of stock in certitude, so I am grateful now to be able to affirm simultaneously that I am a person of faith and that my answer to many religious and spiritual questions is “I don’t know.” Unwavering intellectual assent to a set of black-and-white doctrines is no longer my litmus test for faithfulness. I don’t spend my days worrying about my doubts or feeling like I’ve flunked Christianity because I don’t have concise and elegant answers to every theological conundrum. The spiritual life I have embraced these days is so much bigger, more nuanced, and more three-dimensional than what I once knew.

And so I am startled and even a bit disturbed to find myself asking this question about the progressive Christianity I have wholeheartedly adopted: Is there such a thing as too much mystery? Or, more provocatively: Have I reached a point in my faith life where I’m using mystery as a cop-out? As a refusal to commit, to engage, to bear public and vulnerable-making witness in the name of Jesus? Is it possible to turn mystery into a self-protective shield, so that I won’t have to stand with conviction and urgency in a world that needs to know the healing love of God?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

These questions have been creeping up on me for a while. I think about them every time I see a version of Christianity in the media that is divisive, fear-based, racist, sexist, or nationalistic. I wonder where the impassioned progressive response is. Where is the bold articulation of an alternative Christianity? A Christianity that insists—without polite equivocation—on inclusion, self-sacrificial love, and restorative justice?

I think about the limits of mystery whenever I hear my fellow laity in church settings back away from robust engagement with the Bible, or with church tradition, or with doctrine. As if the mystery of our faith offers the perfect justification for leaving the hard questions and conversations to the scholars in seminaries. If we can’t know for sure anyway, why bother delving in?

I grieve over mystery when it leads church leaders to shy away from calling parishioners to embrace their baptismal vows. When ministry becomes more about keeping everyone happy and less about iron sharpening iron. When invitation loses its beautiful and necessary edge—the edge that prods us forward into discipleship and spiritual growth.

I flinch at mystery when it keeps me from sharing the story of my faith with anyone. As if evangelism requires certainty first. As if the world isn’t in fact hungry to encounter a God sturdy enough and generous enough to exist in the midst of ambiguity, paradox, and contradiction. As if telling my story of a God who loves me and loves my questions is always and automatically an offensive act.

And finally, I worry over mystery when I think about the privileged place I inhabit as a middle-class, comfortably housed, well-educated American. Do I back away from taking stands because I can afford to? Because my personal stakes are so low? If so, then who is hurt by my unwillingness to commit to a knowing that embraces mystery but also transcends it? Who suffers when I shy away from embracing capital-T Truths worth living and dying for?

Yes, it is absolutely the case that our scriptures insist on the importance of mystery in the life of faith. The writer of 1 Timothy insists that “the mystery of our religion is great” (3:16). Paul describes “the mystery that was kept secret for long ages” (Rom. 16:25). Jesus himself speaks of “the secrets of the kingdom of heaven” (Matt. 13:11). Likewise, our 2,000-year-old tradition rightly emphasizes the role of mystery in the Christian life. We are blessed to have a spiritual lexicon that includes such treasures as The Cloud of Unknowing.

And yet we are also the inheritors of revealed truths. Of gracious disclosures. Of God’s astonishing willingness to take on human form so that we can know something of God’s vast and mysterious nature. In the gospels, Jesus doesn’t back away from affirmation; he makes specific claims about what is good and just and loving—and he tells his disciples to go into all the world and do likewise. It is not polite silence in the face of mystery that gets Jesus killed; it is his refusal to water down his convictions.

Likewise, when our spiritual ancestors in the New Testament speak of mystery, it is never as an excuse to back away from deep engagement or risky articulation. In fact, it is just the opposite: the presence of mystery is always an invitation to draw close, to behold, to ask questions. Our response to mystery should be active participation and excavation. It should be pangs of hunger for life-changing discovery.

The invitation embedded in mystery is an invitation to get curious and stay curious, and the gift embedded in mystery is the gift of wonder. Wonder that will lead us to reverence, then love, then proclamation.

In his profound book New Seeds of Contemplation, Thomas Merton writes that in order for any of us to find love, we “must enter into the sanctuary where it is hidden, which is the mystery of God.” There is, in other words, a sacred response that mystery can elicit from us, if we are willing to be called. We are always invited to enter into that holy sanctuary and take a good look around. We are always invited to pursue the One who pursues us, because the end is not unknowing. The end is communion. The end is love.

Great is the mystery of our faith. Let’s dig in.