An anti-Christian lawsuit

When Texas attorney general Ken Paxton filed a suit against a Catholic volunteer organization in El Paso, he went against his own church’s statement of faith.

Hospitality as an exercise of Christian faith is not groundbreaking theology. The hospitality of early Christian communities was so great it earned them the ire of the Roman government. “These impious Galileans not only feed their own poor, but ours also,” wrote emperor Julian the Apostate. “While the pagan priests neglect the poor, the hated Galileans devote themselves to works of charity.” A century later, Saint Benedict insisted to his fellow monks that every guest who arrived on their doorstep “be received as Christ.” More recently, Black Christians in the US hosted escaped enslaved people in their homes as part of the Underground Railroad, and European Christians such as Corrie ten Boom found themselves sent to Nazi concentration camps for harboring Jews in their homes.

Liberation theologians like Gustavo Gutiérrez may have given the practice of Christian hospitality new names or new contexts, but it is not novel in any way. The tradition of Christianity is a tradition of hospitality, one that has flourished alongside, and often despite, a second, equally historic pattern: one of vitriolic, sometimes violent government opposition.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

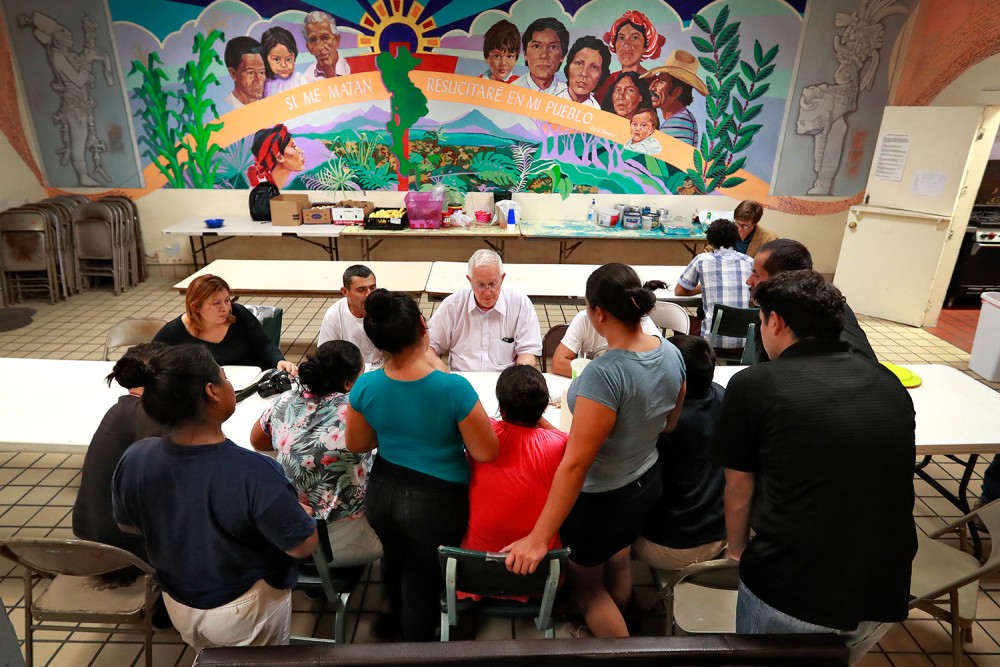

In February, Texas attorney general Ken Paxton announced a lawsuit against Annunciation House, a Catholic organization in El Paso that seeks to “accompany the migrant, refugee, and economically vulnerable peoples of the border region.” The organization runs multiple shelters, staffed almost entirely by volunteers, where migrants are given food, a place to sleep, and a change of clothes. Paxton’s suit claims that Annunciation House is facilitating “astonishing horrors” including human smuggling, lawlessness, and the maintenance of stash houses. (Last week, a state district judge blocked Paxton’s investigation for the time being.)

I lived at Annunciation House for two summers, first as a volunteer and then as an employee. I went there because, in the depth of the pandemic, surrounded by losses both personal and global, I could not understand the purpose of a faith so shallow that it only functioned when I chose to ignore the pain and suffering of others. If my faith could not survive the realities of the world, I did not understand how it could possibly be useful or, more importantly, how it could possibly be true.

The first time I was at Annunciation House, as a volunteer, I did laundry, made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and occasionally helped in the office. The second time, I was a paid coordinator of one of the shelters, managing a team of staff that included firefighters and workers from the city of El Paso.

I have not worked at Annunciation House in almost two years and cannot speak to what the organization has been since I left (although I cannot imagine that the decades-old institution has somehow transformed overnight from active ministry into the stuff of Law & Order: SVU). But I can respond to some of these allegations based on what I did and saw during my time there.

The suit accuses Annunciation House of “maintaining stash houses.” I have sat in these houses and listened with volunteers while the organization’s director played worship songs on an old boom box. I’ve eaten empanadas made by Venezuelan guests in those kitchens, danced with volunteering nuns from out of town to their favorite Pink Martini songs. I took communion alongside guests and sat through masses preached in Spanish about the love of the Father. There is nothing and no one “stashed” in these houses. They exist as places of rest.

The suit accuses Annunciation House of “human smuggling.” The guests I welcomed were brought to us by CBP and ICE, migrants who self-reported themselves to Border Patrol in hope of seeking asylum in the States. Annunciation House does not exist to ferry anyone across the border; it exists to care for those who have already crossed it who would otherwise be sleeping on the streets.

The suit also accuses Annunciation House of “perpetuating lawlessness.” But schools, food banks, churches, hospitals, and businesses throughout Texas all welcome guests without asking them their legal status. This is not an act of illegality but a common practice of a wide variety of organizations. This extends to Ken Paxton’s own church, Prestonwood Baptist in Plano, a tax-exempt organization whose community initiatives include partnerships with local shelters and food banks that serve guests based on their need—regardless of their documentation status.

The work of Annunciation House is the work of the gospel: to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, and love our neighbor as ourselves. To ask Annunciation House to cease its work is to ask it to commit heresy in the name of the state.

The gospel is not a theoretical exercise; faith is not a project of fashion that I can garnish based on what is politically fashionable or personally convenient. I cannot ignore my neighbor to placate an attorney or win an election cycle. I cannot pretend my neighbor does not exist just because he may not come to my doorstep for reasons I agree with or understand. The powers and principalities of the current moment may practice their faith differently, but this does not excuse me from following the Lord my God with all my heart, soul, and strength.

On the Our Beliefs page of Prestonwood Baptist’s website, if you follow the link at the end to “our full statement of faith” you’ll find a Southern Baptist Convention page that includes this quote: “Baptists cherish and defend religious liberty, and deny the right of any secular or religious authority to impose a confession of faith upon a church or body of churches. We honor the principles of soul competency and the priesthood of believers, affirming together both our liberty in Christ and our accountability to each other under the Word of God.”

In the priesthood of believers, whether either of us likes it or not, Ken Paxton and I are side by side. And it is in my accountability to him and his to me that I ask him to acknowledge the work of Annunciation House as the work of religious liberty, work that denies disruption by him or anyone else.