In search of Rumi’s live heart

Looking for an Arabic translation of a favorite line, I found myself on a treasure hunt.

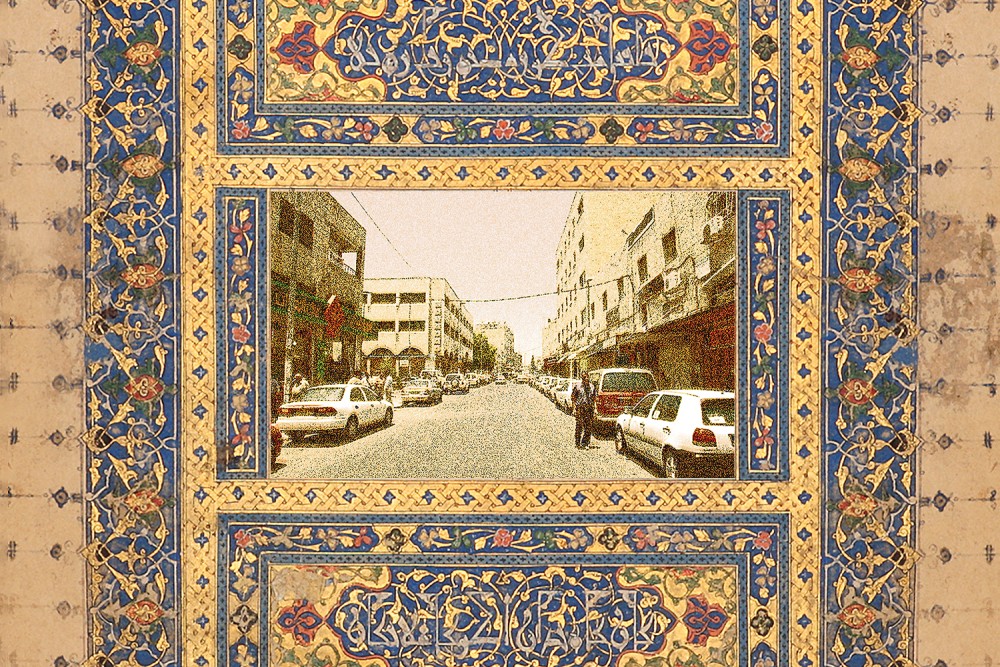

(Century illustration | Sources: Illuminated frontispiece from Rumi’s poems / Creative Commons)

I had never exerted so much energy just to send a text. I wanted to tell the man who had been my guide in Aswan, Egypt, that his kind hospitality, his vulnerability and honesty, his genuine love for his home which he’d shared with a stranger had been deeply meaningful to me. I wanted to send a thank-you text. Although I had left Egypt for the next stage of my trip, Mido and I were now regular correspondents on WhatsApp. I wanted to send him a quotation from Rumi that I had been carrying around with me since I had left home. But while Mido’s English was very good, I thought it might be a bit silly to send him an English translation of a quotation that was surely better translated into one of his native languages.

Now at the Tantur Ecumenical Institute in Jerusalem, I decided, naive about both translation and Rumi, to try to find a translation in Arabic for these lines from the 13th-century Persian poet:

Bring a hundred sacks of gold and God will say, “Bring the heart.” And if you bring a dead heart carried like a coffin on your shoulder, God will say, “O, cheat! Is this a graveyard? Bring the live heart! Bring the live heart!”