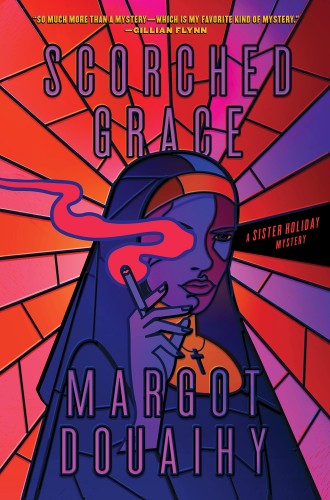

Sister Holiday takes the heat

Margot Douaihy’s New Orleans is a fever dream. Her protagonist is a queer, punk nun who is all in on her vocation.

There are two main characters in Scorched Grace: Sister Holiday Walsh—who makes a lot of her belief that she’s the first punk nun with a past—and the heat, whether from the fire that ravages St. Sebastian, the Catholic school where she teaches guitar as a Sister of the Sublime Blood, or the subtropical steam of the city of New Orleans. Having lived there, I can affirm that this heat, especially in summer, is every bit as oppressive, stultifying, and hallucinatory as Margot Douaihy renders it. This is the poet’s debut novel, the first in a series that has already been optioned for prestige TV.

But the heat is all I recognized of the city. Sister Holiday’s New Orleans is a fever dream where a man walks an alligator on a leash and there are only four Catholic schools and nobody has functional air-conditioning. It will probably look great on-screen, but Douaihy’s literary re-creation of heat exhaustion is so thorough that it results in a plodding pace and a strange suspension of time, a frustrating choice for a thriller. I kept waiting for her to pick up the pace, but she really commits to the bit. She’s so good at writing the hypnotic effects of heat she almost put me to sleep.

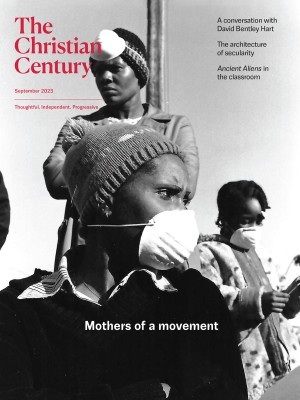

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Douaihy is originally from Scranton, Pennsylvania, and her Rust Belt aesthetic is evident in her interpretation of New Orleans. The city in Scorched Grace is lush but decaying and putrid, almost physically unbearable for anyone without a willful and slightly unhinged streak—the perfect setting for an unlikely nun who sees in destruction and death the opportunity for and necessity of rebirth. “We keep trying because transformation is survival, like Jesus proved,” she muses, considering those who have come to St. Sebastian’s to reinvent themselves just as she did.

But Sister Holiday isn’t merely hiding in the convent. She is a “true believer . . . despite the optics.” She may test the rules, but her faith is genuine; she only doubts herself. She loves the ritual and the order of the Catholic Church even as she despises the way “the diocese”—all men, of course—rules the sisters with suspicion. She also enjoys hiding in the alley to smoke the cigarettes she confiscates from students, which is where she watches the first fire erupt at St. Sebastian’s, skin pruning as sweat rains down her back to puddle at the roots of her tree of life tattoo. I could picture her standing there, undulating in a late afternoon heat mirage. Then a fresh wave of heat overtakes her, and she realizes the east wing of the school is burning. She watches a flaming body drop from the second-floor window before rushing in to help, saving two students who are trapped inside.

This turns out to be the start of an arson spree, but the mystery of who keeps setting fire to the school seems almost beside the point, which is exactly what a reader might expect from a crime novel written by a poet. Meanwhile, the sentences are as ornate as a courtyard garden and the characters as hard as statuary. Sister Holiday, a brokenhearted, tattooed lesbian with bleached blonde hair, a gold tooth, and a troubling past, plays hard-boiled detective. Magnolia Riveaux, the first Black female fire inspector in New Orleans and an opioid-addicted survivor of domestic abuse and institutional sexism and racism, tries to stop her from interfering with the investigation. That these two first-of-their-kind people will develop a caustic but loyal friendship is utterly predictable, but the book’s charm lies in how Douaihy checks the boxes of these genre conventions in her own sweet time. It’s fun to watch her female characters fill out those old plaster casts.

Sister Holiday is brave but she’s also reckless, and she does more to bungle Riveaux’s investigation than to help it. No matter, because the book’s more interesting mystery is what brought Sister Holiday to the convent in the first place, and the gruesomeness of her backstory does not disappoint. The characters we meet in her tormented flashbacks are more richly developed than many of those that populate her present. Her brother Moose, also gay, is a traumatized survivor of a hate crime. Their mother is a terminally ill devout Catholic with an unfulfilled vocation. Nina, her longtime lover, is married to a man.

In time we understand that Holiday’s religious life is, in fact, an act of atonement and penance, but it is no less sincere because of that. When Nina reappears, we see that Holiday takes her vows seriously, including her vow of celibacy. “This isn’t a joke,” she tells Nina. “I’m different now.” Because Douaihy writes sexual pleasure and intimacy even better than she writes heat, we know the cost of that commitment.

We also feel Sister Holiday’s relief at having finally found a way to make sense of herself and all she’s experienced. Elsewhere she ruminates:

What drew me to the Sisters of the Sublime Blood—besides the fact that it was the only convent in North America I thought would consider my candidacy—was its mission statement: To share the light in a dark world. I had seen my fair share of darkness, but Sister Augustine made me feel welcome. . . . I needed a way to make all the contradictions of my life fit. God helped it fit.

Sister Holiday is all in, and that makes it even harder to stomach when she is, in the end, betrayed. The plot twist feels forced, but there’s still a relatable lesson here about who we trust when we don’t trust ourselves.

If the novel isn’t completely successful as a conventional mystery—and even if it too blithely dismisses the standard objections we’d imagine a queer punk woman might have to Catholic doctrine—it’s still a fascinating exploration of the risk of having faith in other people and of what it means to keep your promises. I’m looking forward to finding out what Sister Holiday and her sidekick Riveaux will investigate next, though I do hope it’s set in the winter.