When localism becomes nationalism

At the farmers market, I found something I didn’t expect—White supremacists.

Celebrity farmer Joel Salatin, known to many from Michael Pollan’s best-selling book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, was one of the most influential figures in the local food movement. So it was a blow to many of his fans when his history of appallingly racist remarks and bigotry toward people of color became public knowledge. After an ongoing social media dispute, Mother Earth News, the go-to publication for devotees of the local and sustainable, cut all ties with Salatin in 2020.

To me, the revelation of Salatin’s bigotry was not surprising. I’ve been involved in the local food movement as an eco-grower for nearly 15 years. I’ve sold at farmers markets, supported restaurants and caterers with fresh produce, and organized crop-sharing plans, popularly known as community supported agriculture or CSAs. I have enthusiastically promoted localism as the philosophical underpinning of this work.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But I have become increasingly aware of how threads of White supremacy and ethno-nationalism run through the local movement and through localism in general. After years of vocal advocacy for localism, I now see the ideology’s potential dangers as well.

Localism is the belief that political, social, and economic order should be structured, as much as possible, on a local, communal level. Once a fringe ethos popular among counterculturists, localism has migrated into the mainstream of contemporary society. It’s common these days to prefer the artisanal, small business, and farm-to-table food and to reject big-box stores and suburban sprawl.

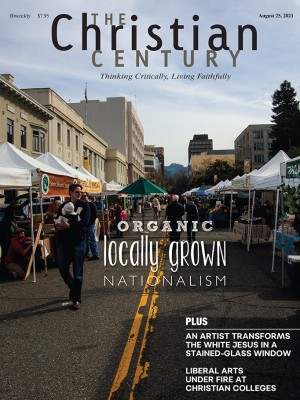

The ultimate symbol of this reorientation toward the local is the farmers market. No longer just a venue for growers to make a little profit off their extra vegetables, farmers markets are now thriving centers of cultural activity, where fashionable professionals pay generously for heirloom produce and artisanal goods and their children learn about soil science while local bands play live music. A good farmers market gives one a sense of belonging, being connected with one’s community and environment. This is localism in action.

Localism is also touted as a political alternative to the extremes of authoritarian, centralized government on the one hand and anarchic lawlessness on the other. In place of a one-size-fits-all approach to legislation, a localist approach would allow regional authorities to address their own problems in their own way. “Localism stands for the idea that there is no one set of solutions to diverse national problems,” writes David Brooks in the New York Times. “Instead, it brings conservatives and liberals together around the thought that people are happiest when their lives are enmeshed in caring face-to-face relationships, building their communities together.”

Brooks may be overly optimistic about localism as a force for political unity, but it’s true that “buy local” resonates across ideological lines. The movement to support local farmers, buy from local businesses, and invest in one’s immediate community attracts activists and organizers of all stripes.

And on a moral level, the appeal of localism is undeniable. It emphasizes care for the environment, economic solidarity, and sustainable practices. The common good may seem abstract when contemplated globally, but localism is predicated on a faith in individuals’ capacity to invest in their own civic order and ecosystems, as well as to understand, concretely, what their communities need to thrive.

Increased wealth disparity and centralization have turned too many of our communities, both urban and rural, into food deserts. The lengthy foodways from corporate farms and factories sometimes end before reaching less advantaged communities—and grow increasingly expensive the longer they extend. It’s not just food, either. Disadvantaged communities are experiencing decreased access to entertainment, education, arts, culture, and medical services. Unjust labor practices and pollution of ecosystems cease to be theoretical and become personal when they are happening in plain view. From the perspective of Christian ethics, localism can be thought of as a way of living out both the mandates of charity and the responsibilities of stewardship.

A chance at political unity, a possible fix to the bleakness of rampant inequality, an emphasis on our moral responsibilities, both to the environment and to the worker—if localism sounds too good to be true, it may be because I have not yet addressed the ways in which it can go tragically wrong. On its own, it is not only insufficient, it can be dangerous. Too great an emphasis on the romance of the immediate can lead to fear of the other. Care for one’s own community can morph into isolationism. Localism can bleed into nationalism—and even White supremacy.

There was a time when I was unaware of this overlap. I rarely discussed politics with other growers; I assumed people who were invested in local food and sustainable agriculture must be liberal or progressive. I associated a familiar hippie farmers market aesthetic with ecological responsibility, multiculturalism, and peaceful coexistence.

In 2016, when I lost several customers because of my opposition to Donald Trump and his “America first” ideology, I didn’t think much of it; I assumed that the wholesome ethos of natural food and sustainable living would inoculate the localist community against ideologies of hate. But then more people I knew who were involved in sustainable practices came out as pro-Trump and anti-immigrant. I was astonished by growers who reviled Muslims and spread hateful slander about refugees while selling heirloom varietals that had been developed in Latin American and Middle Eastern nations.

When I talked to progressive local food advocates, they suggested that my increasing experiences of White supremacy in local food movements were limited to my region—I live in rural Appalachia. But it is not just Appalachia.

Farmers markets across the nation and even abroad have, in recent years, begun to attract White supremacist groups. Kelly Weill reported in the Daily Beast that “the far right’s love of the markets plays into a larger fascist talking point that idealizes pastoral life and demonizes ‘degenerate’ urban living. The contrast attempts to cast white supremacy as a purer alternative.” Weill’s story was inspired by a 2019 incident in the progressive college town of Bloomington, Indiana, in which a local farmers market ousted farmer Sarah Dye, known as “Volkmom” in the White supremacist group Identity Evropa. Other farmers began to sell pins that read “Don’t buy veggies from Nazis.”

Yes, the “America first” ideology is widespread in our rural communities, where a preference for natural food and holistic medicine doesn’t always signal progressive politics but rather a distrust of urban liberals, coastal elites, and shadowy globalist influences. But a similar mechanism has functioned in anti-globalist movements abroad, connecting love of the local with fear of foreign influence and opposition to the influx of ethnically diverse immigrant groups.

Consider the Brexit phenomenon in the United Kingdom. While the movement to leave the European Union was driven by many complex factors, including a distrust of neoliberal capitalism, Brexit likely never would have happened were it not for a spirit of hostility to and fear of the outsider—specifically, the UK’s diverse immigrant population. So it is troubling to note that, according to a survey by industry publication Farmers Weekly, a majority of farmers voted to leave the EU in spite of forecasts that Brexit would harm farmers and farming. It is hard to think of the British agrarian countryside as anything other than benign, but the painful truth is that these communities are overwhelmingly White.

VV Brown writes in the Guardian about her experience as an ethnic minority in the British countryside: “The anticipation of negative reactions to my presence has become tiresome. . . . It’s important to understand that ignorant, racist things can come out of the mouths of nice smiley people in wellington boots.”

In Sweden, neo-Nazi extremist groups have infiltrated local food movements. Heléne Lööw, an expert on fascism, told the New York Times:

“I have hardly met anyone from these movements, neither the old ones nor the young ones, who are not serving me organic food, and lecturing me about the dangers of fast food, the dangers of McDonald’s.” . . . As a consequence, a neo-Nazi group like the Nordic Resistance Movement is occasionally represented at local farmers’ markets. “When people meet them in real life, they are not their media image. People get surprised. They are nice, they are talkative, they offer you a lot of good food.”

In recent years eco-fascism has blossomed among extremist branches of environmentalism that connect protection of natural resources with the preservation of national and ethnic purity. The mass shooters at El Paso, Texas, and Christchurch, New Zealand, both held extremist environmentalist views and far-right White nationalist prejudices. Jake Angeli, the man known as Q Shaman who stormed the Capitol wearing horns and fur, demanded an all-organic diet in jail.

But the segue from localism to White nationalism is not just a danger for secular extremists and so-called Nordic pagans. (Many Nordic pagans decry racism and the use of their religious symbols by extremists.) These harmful ideologies have also taken root among Christians concerned with moral purity.

Among traditionalist Catholics, one localist trend was labeled by writer Rod Dreher—himself a preeminent spokesman for polite Christian ethno-nationalism—as “crunchy conservatism.” The “crunchy cons” wed environmentalism and holistic living with traditional social mores, withdrawing from the influence of the globalized and secularized world. Piggybacking off this, Dreher proposed his “Benedict Option”—a suggestion that Christians should follow the example of St. Benedict of Nursia by distancing themselves from the evils of the world and living in intentional community with others of shared values.

Emma Green of the Atlantic recently profiled the traditional Catholic community in St. Marys, Kansas, presenting it as emblematic of what Dreher had in mind. The town is dominated by members of an extremely traditionalist sect:

St. Marys is home to a chapter of the Society of St. Pius X, or SSPX. Named for the early-20th-century pope who railed against the forces of modernism, the international order of priests was formed in the aftermath of the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church’s attempt, in the 1960s, to meet the challenges of contemporary life. Though not fully recognized by the Vatican, the priests of SSPX see themselves as defenders of the true practices of Roman Catholicism, including the traditional Latin Mass, celebrated each day in St. Marys.

What initially looks like an idyllic—if somewhat old-fashioned—community of believers, where everyone learns Latin and the schools use blackboards instead of computers, becomes ominous when one learns about SSPX’s history of racism and antisemitism. Green even notes a photograph in the town’s school prominently featuring a Holocaust denier.

St. Marys is not the only Catholic example, and it’s not only Catholics doing it. Green points to several other examples of religious communities moving out of diverse cities into demographically homogeneous enclaves.

Such Christian separatist communities share with secular eco-fascists an obsession with purity that can become deadly.

Localism argues for the purity of our food and land. In far-right nationalist and fascist ideologies, purity also implies purity of race, purity of blood, and a dread of the ethnic outsider as a contaminant, unclean. Emphasis is on the “traditional,” racially pure family in which everyone abides by rigid gender roles. The “blood and soil” rhetoric of the Nazi regime advanced these prejudices. Love of land, generally understood as a positive virtue, becomes a gateway to prejudice.

Distinctions between insiders and outsiders become crucial to group identity, with all that is depraved and corrupt relegated to the dangerous world outside the closed circle. “Do you want the people who turned their neighborhood a shithole to bring the shithole to your street?” Dreher wrote on his blog for the American Conservative. If the world is envisioned in the form of non-White immigrants and urban Black communities, what initially looked like a path for escaping the world’s evils becomes a recipe for fostering them. Localism without a sense of larger responsibility begins to look like xenophobia with an environmentally conscious twist.

Nor is embracing diversity enough to avoid the dangers of localism. Denying global responsibility—thinking of human actions only in terms of individual self-fulfillment or the needs of one’s close circle—is potentially disastrous. The pandemic has made this especially clear, as those who opt to self-determine and “take the risk” without consideration of broader consequences drive up the infection rate and harm others. And the discrepancies in local public health measures reflect discrepancies in how different communities deal—or don’t deal—with structural racism. Robert W. Snyder and Fritz Umbach addressed this in an article for the New York Daily News called “Pandemics, Policing and the Curse of Localism”:

Only through national institutions reflecting our common humanity can we do a better job of caring for each other and enforcing our laws. In both public health and policing, where local variations can mean killing or healing, the inequalities inherent in decentralized federalism violate our national aspirations for equal rights and universal justice.

It is insufficient for communities to enclose themselves and create structures of justice that are disconnected from the broader human community. Efforts for equity and healing must look beyond the immediate. Failure to do so reveals a stunted spiritual anthropology that limits collective identity to the next door or the backyard. Yes, we are commanded to care for our neighbor. But the Gospel parable reminds us that the stranger and the foreigner are our neighbors as well. We need to be mindful of our vast network of interconnections—and of the way our actions affect not only our neighbors but also those outside our immediate circles. Human societies and the ecosystems in which they are rooted are intimately, intricately connected, no matter how desperately some may want to believe that isolation is possible.

“Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly,” wrote Martin Luther King Jr. from Birmingham Jail. The transformative power of human action, for good or for evil, touches the whole world. If our actions are not guided by this principle, we risk a false localism that impoverishes itself and damages the common good.

In our enthusiasm to reorient our politics and economics toward the local, we need to be aware of how localism can go wrong. This means learning to recognize strains of thinking that, intentionally or not, can lead to nationalist prejudices. Variants on localism that normalize prejudice or insist on a closed community, rather than intersecting communities with open gates and doors, are dangerous. Words like globalist are often deployed as a dog whistle for “Jewish”—as a covert antisemitic slur. Localism as a defense of Western values, or as a preservation of White, Western civilization as some kind of fundamentally superior society, is shorthand for White supremacy.

Understanding those rhetorical and philosophical tropes that reinforce nationalist or White supremacist notions can help us in our work to promote a humane and just localism, to be prudent when choosing which movements to work with and which thought leaders to elevate. I realized at my own farmers market that I can’t form coalitions simply on the basis of shared interests in sustainability or environmental protection—though perhaps such commonalities could be the basis for helping others to see localism as a global project and outsiders as valuable partners.

It is important to center non-White leaders in the local food movement—and to take advantage of opportunities for global collaboration. The heirloom varietals sought at the local grower’s stand are a tribute to the labor of other growers who lovingly cultivated these strains in other soils, in other cultures, yet some of these varietals are also beautifully adapted to one’s home soil. My preferred variety of romaine lettuce, which stands up to the heat and drought of an Ohio summer, was developed in Israel. I grow tomatoes from Russia, peppers from Portugal. Some of the most cherished fruit and vegetable varietals sold today traveled to our nation in the pockets of immigrants who carried with them their families’ heirlooms in the form of plants, fruits, and seeds.

To be clear, I still believe in localism. As a grower, I am invested in my local land and economy, even as I rely on and support broader networks. As a Christian, I see the land that sustains me as holy, while also recognizing my call to the stewardship of all creation, not just my immediate environs.

Without that balance, localism can be dangerous. And aside from the dangers I have explored here, the reality is that localism alone cannot shoulder the burden of caring for our neighbors and communities. On a practical level we are more interconnected than we sometimes realize. The environmental choices made on a personal or local level affect others, so a self-contained localist approach to environmental issues is fundamentally self-defeating. Our human connections extend beyond the immediate, stretching from region to region, nation to nation. So do our ecosystems, and so does our church—the ecclesia embraces both the local and the universal.

Pope Francis affirmed this in Laudato si’. The encyclical refers to the earth as “our common home” and calls for a “global ecological conversion.” Christians who eschew globalism as a modernist invention and prefer to enclose themselves within narrow purlieus are not only embracing a flawed conception of sustainability, they are also rejecting the traditional teachings of their faith. The church cannot be reduced to local communities, yet at the same time, these local communities are where the universal church is made present and real. Real bodies of living persons, the individual physicality of the sacraments, are where the church is manifested.

To live as Christians in relation to the earth and our communities means to recognize holiness in the local, holiness in the earth we touch and the air we breathe and the water we drink. This may be the only way to stave off environmental disaster. And yet the sacredness of one place is inextricably linked to all other places, mirroring the holiness of all creation. The embrace of the local is Christian obligation. But when that embrace leads to suspicion of the other—or denial of our broader connections—we are on dangerous ground.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Homegrown nationalism.”