Immigration law and the politics of disgust

How Pharaoh treated the Hebrews and how the US has treated my people

In the late 19th century, Mexican Americans began to build houses in Chavez Ravine, a 30-minute walk from downtown Los Angeles—pushed to the outskirts of the city by the social forces of racial discrimination. Over the years, other immigrants joined the community, which became three neighborhoods: Bishop, Palo Verde, and La Loma. In the mid-20th century, as the city expanded, municipal authorities plotted to acquire the land with funding from the National Housing Act of 1949. Under the auspices of redevelopment, they seized the property by eminent domain—promising that the residents would be allowed to return after the builders finished a public housing project.

Mayor Norris Poulson did not keep his city’s promise to the inhabitants of Chavez Ravine. Instead of public housing, which he characterized as communist cells, Poulson negotiated the transfer of the land to the Dodgers franchise for a new ballpark, to lure them from Brooklyn. “We’ve got to support and strengthen the downtown area,” Poulson argued. “No city can be a great city without a strong central core.”

With bulldozers behind them, the police swept through the neighborhoods and arrested whoever refused to leave their homes. Dodger Stadium was built in time for the 1962 season. The racism of urban planning displaced Mexican Americans, Chicanos, Mexicans, and Central and South American immigrants, relocating whole neighborhoods to areas east and south of downtown.

This topology of race directed my Costa Rican mother and Colombian father to a community tucked between industrial parks, in the long shadow cast by urban renewal. Our home was a quick drive from the plant where my dad worked, first as a janitor and then on the factory floor as a machinist—a safe distance from Mayor Poulson’s cultural core. The racial forces that organize society pressed our lives toward the manufacturing hub of the region, rendering my dad’s labor easily accessible to economic production fit for immigrants.

At the end of Genesis, socioeconomic forces pull the Hebrews into Egypt to survive the devastation of a famine. The cries of hungry children compel them to pick up their lives and migrate. At the direction of Pharaoh, the Hebrews settle in a region called Goshen—an area on the outskirts of the core of Egyptian life, distant from the culture’s center. “Goshen was quite near the frontier,” Nahum M. Sarna explains in Understanding Genesis. The region was home to “a ‘mixed multitude’ [Exod. 12:38] of non-Egyptians” in “physical isolation from the mainstream of Egyptian life.” Pharaoh’s imperial society was like the geography of Poulson’s Los Angeles, with migrants dispersed into fringe real estate.

As the Hebrew men, the sons of Jacob, prepare for an audience with Pharaoh, their brother Joseph coaches them on how to respond to questions, how to stay out of trouble in this oppressive system he’s learned to navigate over the decades of his assimilation. “When Pharaoh calls for you and says, ‘What is it you do?,’ you shall say, ‘Your servants have been handlers of livestock from our youth until now.’” (All biblical quotes are from Robert Alter’s 2018 translation The Hebrew Bible.) They are to present themselves as useful subjects, valuable to the economy, essential labor.

Joseph also warns them of a cultural reality: “all shepherds are abhorrent to the Egyptians” (Gen. 46:34). A politics of abhorrence characterizes the reception of the Hebrews. They are invited to an Egyptian feast but have to sit apart from the rest of the guests, at a segregated table—“for the Egyptians would not eat bread with the Hebrews, as it was abhorrent to Egypt” (43:32).

Despite the disparaging gaze of the long-standing residents of the land, the Hebrews make a home in this foreign land. They will do anything to keep their kids alive, even if this relocation will mean undergoing their new neighbors’ disgust.

After a while the factory where my dad worked moved the production line to a manufacturing compound in Tucson, Arizona, in search of a cheaper labor force. Our family had to follow the job. Immigrant lives serve the economy as precarious workers, available for relocation at the whim of a company’s bottom dollar.

However, my parents soon discovered that, with the money from selling our house in California, we could afford to live in a much nicer neighborhood in Tucson, nicer than people like us were supposed to be allowed to live in. Instead of buying a house in South Tucson, close to the factories, my parents found a spot in the northern part of the city, near the foothills. The plant manager lived up the hill from our home, in the same development but above us, in a house with a view. Civilization has always built its hierarchies into the environment.

The four of us—my mom, dad, sister, and I—were the only non-White people in the area. The neighbors had Lexuses; we had an ocean blue 1960s Volkswagen Bug, well used by previous owners and then by us. On weekends the car would be up on a ramp or jacks in our driveway so my dad could change the oil or figure out how to fix a mechanical issue—whatever it took to keep the thing running. We did our own domestic work, our own yard work. We hung our laundry on clotheslines in the backyard to dry. My dad rarely wore a shirt outside.

In the two decades since I left that community, the demographics have shifted slightly. My parents were the advance guard of what White supremacists have called “the brown invasion”—a racist trope with a long history in the United States, now a political theme at home in the social vision of the sitting president. “We cannot allow all of these people to invade our country,” President Trump wrote on Twitter in June 2018 about people crossing the southern border into the United States.

His attorney general used the same language a month earlier, as if the two were passing around their party’s handbook on nationalism. “We are not going to let this country be invaded,” Jeff Sessions said at a law enforcement conference in Scottsdale, Arizona, a two-hour drive from my parents.

In the biblical story, the abhorred Hebrews “swarmed and multiplied and grew very vast, and the land was filled with them.” Pharaoh and his people take stock of the demographic trends. These foreigners would become “more numerous and vaster than we,” Pharaoh worries aloud at the data, “and then, should war occur, they will actually join our enemies and fight against us and go up from the land” (Exod. 1:7–10). Pharaoh’s Egypt requires precarious Hebrew labor—workers who are indentured to the economy for their own livelihood yet whose personhood is considered alien to the cultural and political identity of the empire. Pharaoh needs them for the function of his society even though his fear converts their foreignness into a security threat.

Here in the United States, a country established as a settler colony, non-European immigrants disrupt the social dominion of Whiteness. As Nelson Maldonado-Torres explains in Against War, the Latino is “a cultural terrorist of sorts who menaces the cultural integrity of the nation.” Immigrant outsiders disintegrate the hold of Euro-nationalism, posing a political danger for those who have invested in the structures power built over the generations.

“The overwhelming oppression is the collective fact that we do not fit,” Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa writes of her Chicana identity in La Prieta, “and because we do not fit we are a threat.” As Latino peoples in the United States, we are like the Hebrews in Egypt—a threat to the ethno-nationalist founders and the contemporary heirs of their dreams.

The election of Donald Trump was a last-ditch effort on behalf of American Whiteness to consolidate power, to socially engineer a future for this country that isn’t so Brown. His administration’s response to the demographic shift—a country becoming less White and less Christian—has been a wide-ranging detention and deportation strategy and a protracted effort to refuse asylum applicants and deny refugees from Muslim-majority countries.

These federal directives cohere into a scattershot strategy to protect European legacies of racial dominance, to control who will be our neighbors. Immigration policies are about social formation—the making of a peoplehood, the construction of our identity. The political is personal, reaching into the intimacies of our friendships, of who we belong to and who belongs to us—in our families, churches, and neighborhoods.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed US society as indebted to an economy of domination, a work structure that asserts a hierarchy of human value. In June an evening news segment on Univision featured field-workers in Florida who have been told that they are essential to the food supply yet haven’t been allowed a process to get legal documents to live in this society without fear of deportation. “Antes nos decían ilegales y ahora somos esenciales,” Claudia Gonzalez, an organizer with the Farmworker Association of Florida, told the reporter. They used to call us illegals, but now we’re essential. Legislators have set up a legal system that abhors the thought of residency permits for undocumented workers. Our economy demands their labor, while the political regime detests their inclusion as citizens.

This past summer in North Carolina, where I live, nearly half of all cases of infection were among Latino people, while we make up only 10 percent of the population. Our state led all the others in outbreaks in meatpacking factories, where Latinos are most of the workforce. In our county the numbers have been even worse: in June almost 80 percent of the cases were among members of the Latino community; we’re 13 percent of the population.

There have been rumors of outbreaks at major construction sites around town, where Latino labor fuels developers’ schemes to gentrify our city. These crews risk their lives during this pandemic to frame and drywall and roof buildings in which they could never afford to live. Essential to the moneyed class for a month, then shoved by the invisible hand of the market into neighborhoods on the other side of the highway, far away from public transit and community resources, in food deserts.

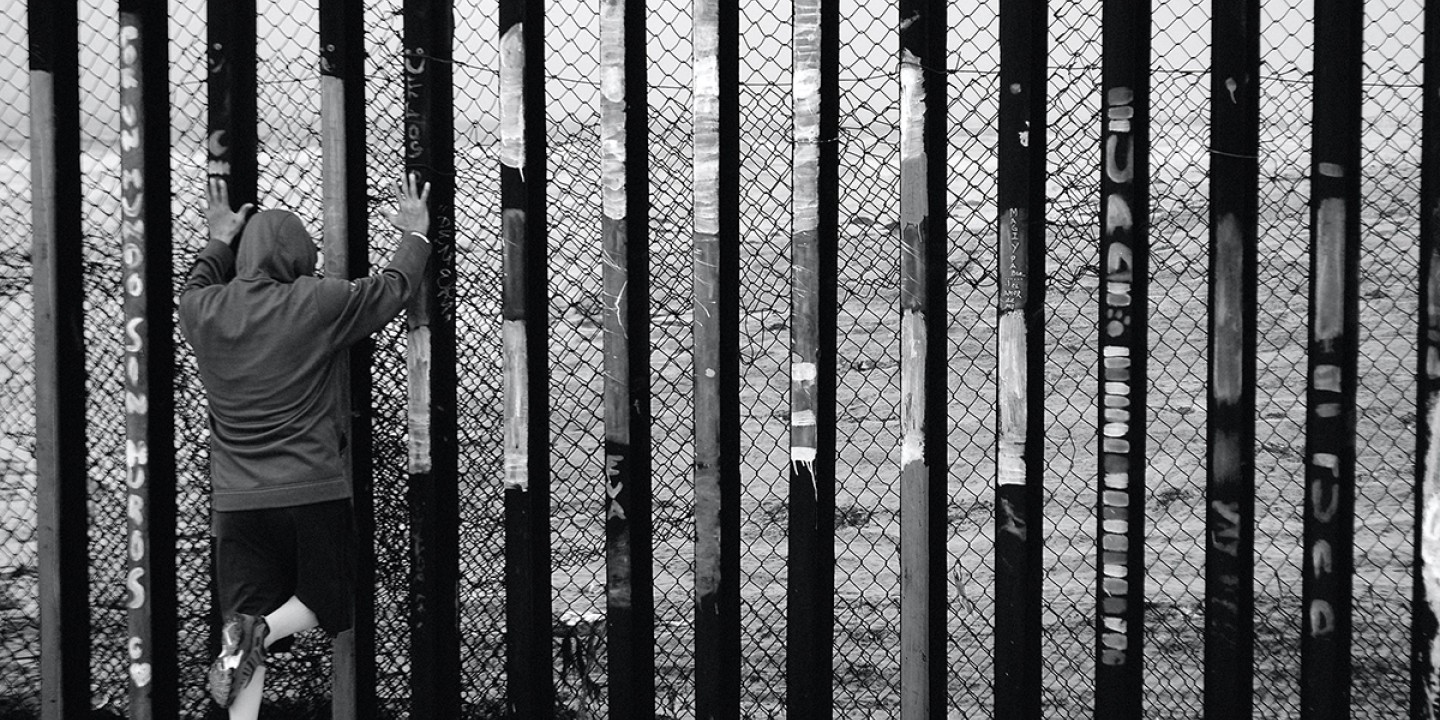

For the US, power depends on segregation on a global scale, enforced by immigration policy and militarized borders, in order to produce a sense of peoplehood—to code individuals according to the laws of citizenship, which require that some are categorized as alien, as foreign, as migrant. The rights and privileges of every US citizen depend on maintaining a legal difference from others as aliens. Citizenship is invested in a politics of confinement, a carceral geography.

US power excludes people from citizenship and residency in order to restrict the natural movement of human life. The policing of migrants allows US society to plunder the wealth on the other side of borders while fencing out people desperate for the livelihood stolen from them. Border security enacts structures of confinement, rendering migrants as indentured servants to the global economy and pawns in the political schemes of superpowers. “Migrant and undocumented workers thus are the flip side of transnational capitalist outsourcing,” Harsha Walia explains in Undoing Border Imperialism, “which itself requires border imperialism and racialized empire to create differential zones of labor.” The nationalist commitments of the United States admit the flow of capital while regulating transnational demographics by excluding foreign bodies—renaming neighbors as enemies of the law, as threats to a way of life.

In Exodus, God liberates the Hebrews for worship. “When you bring the people out from Egypt,” God says to Moses, “you shall worship God on this mountain” (Exod. 3:12). In his audience with Pharaoh, Moses demands that the people be freed in order to assemble in the wilderness to celebrate a festival with God (5:1). Liberation from that oppressive regime is indispensable for religious practice. Worship involves liberation.

For us to worship this same God of the Hebrews implies a political struggle to liberate the world and ourselves from the ethno-nationalism of the US imperial regime. Worship is a pledge to our neighbors, near and far, that our freedom is bound up with theirs. Emma Lazarus declared her solidarity with Jewish people across the globe: “Until we are all free, we are none of us free.” Fannie Lou Hamer adapted this line for the civil rights movement: “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

Worship is solidarity with God’s movement of liberation, even if that labor for freedom involves the undoing of a society that benefits citizens, those of us whose legal status renders others illegal. The meaning of citizenship is established with every death in the borderland, with every person deported, and with every child caged in a detention center. This violence of the law, which attempts to segregate citizen from noncitizen, returns us to Pharaoh’s world. It’s a world in which the customs of abhorrence police society.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The politics of disgust.” Family photos appear courtesy of the author.