The words I turn to in times of grief and distress

“If it can’t be happy, make it beautiful.”

Years ago a close friend called me. “I’ve got a favor to ask,” she said. “A couple of friends were at a graduation you spoke at a month ago, and they liked your sermon.” I sat up. I pieced the facts together. Liked sermon—nice. Remembered sermon—rare. Were sufficiently excited to tell a friend about it a month later—practically unheard of. The quickest way to my ear is through my ego, so my friend had me on a string.

“OK, you’ve given me the charm offensive,” I said, in my best you-do-realize-I-have-a-thousand-calls-upon-my-time voice. “Now, what’s the favor?”

“Well, one of them is dying, and I was hoping you could visit with him. He’s not said anything positive about faith for a long time, and he won’t talk to his wife about anything serious, and we thought, well, maybe he’d talk to you.”

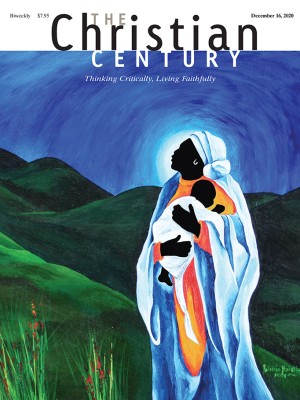

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I tell colleagues that when you get a call like this—to go to the bedside of a dying person, to sit with a human being as they ponder their mortality and face up to the hardest things in their life—your heart should miss a beat. You should think, This is what I was ordained for; this is the most important thing I do; this is what all my training and experience have prepared me for. If you don’t, you might want to reflect on whether you’re in the right profession.

The dying man and I had a long and searching conversation. We spoke about death as nothingness and whether that is the worst thing possible. We discussed relationship, love, and whether love is stronger than death. We explored the wonder of life, the absurdity of death, and whether the combination of life and love and whatever created them is so dynamic that death can’t have the last word. Finally we thought about trust: Does hope finally lie in entrusting our lives to whatever it is that is the source of life and love?

A few days later I went on vacation. This was back when emails and texts didn’t chase you up hill and down dale. When I came back I found a message that said death was near, and the saddest thing was that he wasn’t going to make it to his daughter’s wedding in December.

So I said, “Let’s do it this Saturday.” And we did. He was determined to walk her down the aisle; instead he joined her at the front pew and strode the last half-dozen steps. As he handed over her arm to her intended, I sensed the words of Simeon: “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace.”

After the service, my mind went back to a conversation ten years earlier. “How about you, Sam? What would you like written on your tombstone?” It was the kind of conversation you imagine having with your fellow hostage when an insurgent group has kidnapped you and left you in an attic for years on end. In fact, it was with a roomful of people I’d only just met. In such conversations, I tend to remember either the things that I put into words instantaneously that I previously didn’t know I thought or the things I only realized later, hours or years after the conversation, that I wish I’d said.

This time it was the first kind. “If it can’t be happy, make it beautiful.” I didn’t know where it came from. It landed, fully formed.

All these years later, I haven’t changed my mind. (Except I doubt I’ll have a tombstone at all: when you’re in eternity, trying to shape what people think of you for the first few decades after you’ve gone seems the wrong place to put your energy.) In fact that expression has become my template for almost every occasion when friends or congregation members face profound grief, their own mortality, or terrible distress. As a widower plans a funeral, or as a person faces another kind of loss, I invariably return to those simple words: “I hope that, in the midst of your sorrow and the bleakness of what you’re facing, you can yet find a way to make it beautiful.”

Notice those words don’t say, “If it can’t be good.” Beauty isn’t an alternative to goodness; it isn’t a distraction from depth, seriousness, honesty, or integrity. Nor do they say, “Make it pretty.” Making it beautiful is about realizing we’re usually operating on a mundane level, where things will seldom make sense and where most things are fragile and contingent. In the face of dismay, the best approach is to go up a level, to a realm of fittingness, recalibrated priorities, and God’s kingdom. But making it beautiful also addresses the powerlessness at the heart of grief. There is, it turns out, something you can do, and that is to take the wisdom, grace, or soul of what’s been lost and portray its transcendent quality in word, deed, or collective gesture.

For my new friend, giving his daughter away was just such a gesture. He died four days later. But we’d all done something beautiful together, and when we gathered for his funeral, the beauty of the one blended into the beauty of the other. It was good. It was true.

The pandemic has been an experience of powerlessness and sadness for most of us. It hasn’t been happy. But we can still make it beautiful.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Make it beautiful.”