Bringing forth Lazarus from a blank canvas

“Life is built, and then it stops, and then Christ reaches in and brings it forward again.”

Ross Wilson is an internationally acclaimed artist who was honored by Queen Elizabeth II with a British Empire Medal. If you visit London, you can see his portraits of Seamus Heaney and Derek Walcott in the National Portrait Gallery; his work is also in the Tate Britain. Fans of C. S. Lewis may recognize Wilson’s sculpture in Belfast, The Searcher, which depicts Lewis opening the wardrobe from The Chronicles of Narnia.

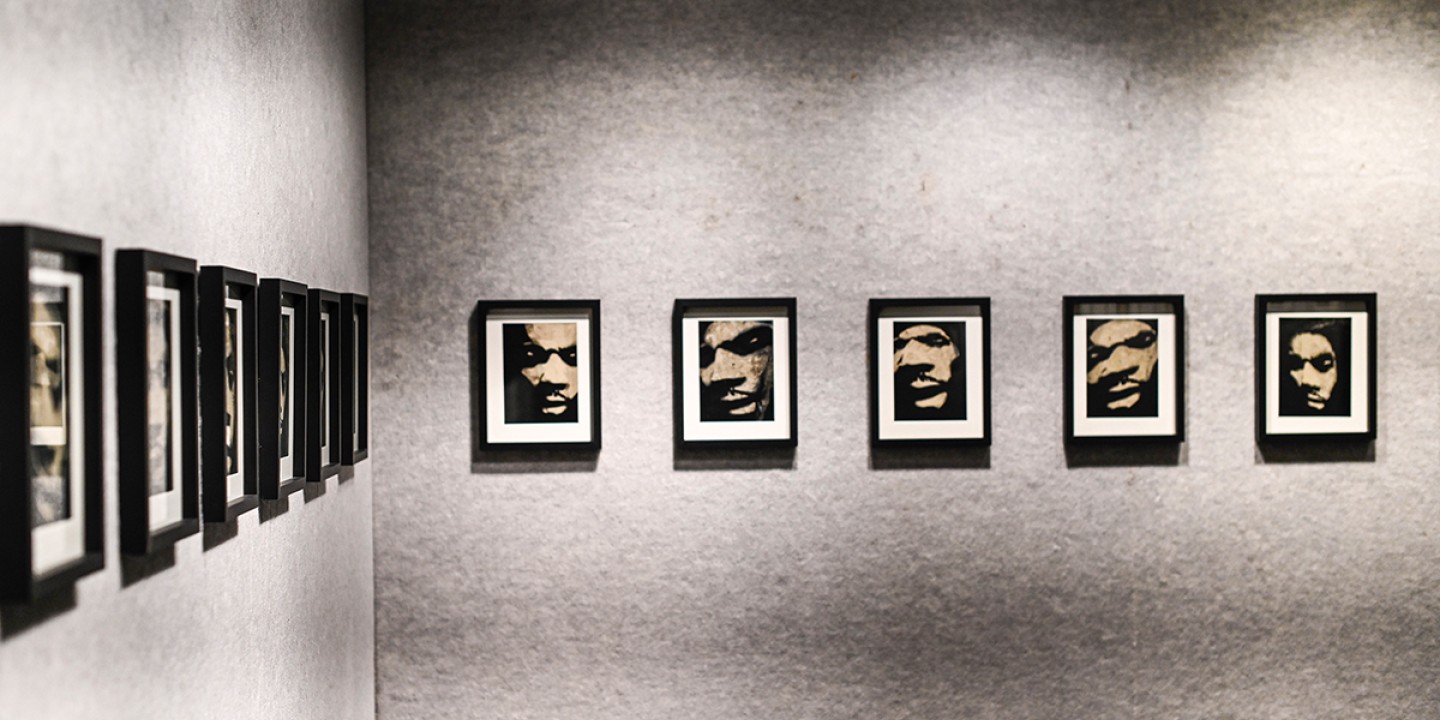

In November 2019, Wilson created a series of 60 portraits of Lazarus, The Calling of Lazarus, for the Windgate Art Gallery at John Brown University, where I teach. The exhibit consists of portraits of equal size that line the gallery’s three walls like a roll of film being spread out. Wilson’s aim is to show Lazarus at the instant of animation, when he hears the voice of Jesus call, “Lazarus, come forth.” Notably, Lazarus’s features are African American.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The evening I first saw the exhibit, I found myself filled with a wordless gratitude. I wanted to dig more deeply into why these paintings are so effective, so I asked Wilson if we could talk about them. He spoke to me from his home in Northern Ireland.

You’re known for your portraits and sculptures. Why are you drawn to depicting real people?

People are important, but it’s difficult to represent someone. Portraits are a very instinctive thing. When I’m mixing colors, I don’t know the names of the colors; I know how to color by sight. I learned growing up that if I see someone doing something, I can usually repeat it.

The great American abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning described what he was trying to do in his work: he said that he was a “slipping glimpser.” In a way, I’m a slipping glimpser—but some of those times that I’m slipping, I’m slipping forward, which is a good thing. Sometimes slipping can take you into places that you would normally not go. It’s very organic, and I make a lot of mistakes. But sometimes you get to the right thing and it holds in the correct way.

What is the “right way” to capture faces and bring forth their presence?

To capture the likeness of a person in a portrait is not just a recording job. There’s an unseen likeness, and you want to get to the center of that likeness. Sometimes you get to that place in the portrait where you know that you’re with the person in the right place. It happens rarely.

The first time I remember it happening was when I painted Derek Walcott. I wanted to put the heat of the place and the heat of his words into the portrait. It was a difficult thing to do because of the pressure: it was for the National Portrait Gallery in London, my first big breakthrough.

Why did you decide to paint Lazarus?

The Lazarus portraits have an unusual starting point. The Lazarus story is amazing, with the idea of God’s timing and the empathy Christ shows to a person whom he loved as his friend. The Lazarus and Zacchaeus stories both fascinate me because they’re both about people being called out: one is called down a tree, and one is called out of death. Christ knew Lazarus before he called him. That idea was really important to me.

Then I heard a song called “Lazarus” by Trip Lee, a hip-hop setting of the scripture passage. I saw a video on YouTube, with a group of dancers dancing to the song, which is absolutely unbelievable. It mesmerized me. The dancing was an important part of how they interpreted the story.

Lee wrote that song from his cultural position, which is a very different cultural position from mine, even though both of us were looking at the same truth. He was seeing it, and I was too, but in a different way. I saw what Lazarus was like through Lee’s eyes in that song. I perceived the story through the eyes of an African American, and I’d never felt that before. I was thrown a little.

In contrast with your Walcott and Heaney portraits, the Lazarus portraits aren’t based on a live person. Is there a different process for creating a portrait of someone you can’t see?

There’s more liberty when you’re creating a new narrative, a new image. With a portrait commission, you’re working with an established recognizable visage or likeness. With the Lazarus portraits, I had control over what he was going to look like. The idea of trying to make an animation from those 60 paintings emerged as I was painting them.

What you’re doing with your art is glossing the biblical story. What do you hope people understand differently after experiencing your work?

The mechanics of the episode are the key to these portraits. The idea of Christ calling someone from death, and the idea of Lazarus being catapulted from death to life in a matter of seconds. I kept saying the words that Christ says: “Lazarus, come forth.” Even with a dramatic pause, it happens easily within 20 seconds. The dead man comes out. There’s no hesitation.

When you spoke in chapel at our university, you summarized the four stages of death: pallor mortis, paleness; algor mortis, cooling of the body; rigor mortis, stiffening of muscles; and livor mortis, when blood moves by gravity to the dependent part of the body. Then you asked students to consider, “What was it like for Lazarus when his blood warmed again, when his lungs filled with oxygen, when strength entered his pale, cold body, to have life come into him from the voice of Jesus?”

The direct structure and mechanics of the miracle are important—the cosmic reality of what happened internally with Lazarus. Lazarus was called out, and he came out directly through the four stages of death because of Christ’s words. Not only is it profound, not only it is ethereal, not only is it hard to grasp when you look into it, but it is the power of Christ and his words and his identity as the Word.

These portraits are a weak illustration of the power of Christ. Even though they are pictures of Lazarus, they are pictures of Christ. They’re portraits of Christ because they show the effect that Christ is having on Lazarus. We can’t always see that when we look at other people. It’s a rare thing to see the effect of Christ moving in people’s lives.

The same Spirit that animates Lazarus animates us still, and there’s something invigorating about seeing the story in these portraits. They make us slow down and pay attention, to see Christ in every second. Each painting represents a second in that reanimation process.

Yes, it’s like a 60-point sermon.

Where each point of the sermon is to look more closely.

These portraits are made by excavating beneath the surface. That was deliberate: the way they are built up and taken back.

Can you talk more about that process?

It’s a process that always intrigued me, even when I was a student. I realized you could make something by taking things away. Making art isn’t just about applying something. You can create by erasing, or by taking a cloth to a painting and rubbing paint off. That’s a fearful thing to do, but it can also get you to that place where big things happen. I used to do a lot of drawing, and I would rub, using an eraser, to give shadow and shade. Then I realized I could use a Black and Decker sander instead of an eraser.

It’s like an excavation. These 60 portraits have been built up and then sanded back, then rebuilt and back again. It’s about going back and forth. That process symbolizes the subject matter too: this life is built, and then it stops, and then Christ reaches in and brings it forward again.

As an artist, what did you learn about the resurrection from the process of the paintings?

The thing that really hit me when I was studying scripture—I’d never really studied that passage in such depth before—was the power of life in Christ’s words. Jesus’ commitment to go to his friend felt really theological to me. Just like Trip Lee’s song. Some things we see, but there are other things that we only hope for. We have the advantage of seeing the full story in hindsight, but still wondering why.

That’s the hard part of the story for me. That Jesus lets Lazarus die. Your paintings demand, through their starkness and lack of color, that believers wrestle with this reality—and the corresponding reality of Good Friday.

Basically, there are only two colors: black and a buffed titanium. But there are a lot of midtones in between where the colors mixed. Even with a limited palette like that, it can be quite complex.

The darkness of the paintings draws people into contemplating more viscerally the deaths.

Yes, and it’s a close-up image. There’s a bit of artistic license there. In the narrative, Lazarus was covered up. But the portraits look through that darkness to the moment which will bring joy and which will bring unity to a family again. The other darkness to think about is post-miracle: in chapter 12, the chief priests decide to kill the miracle. They are so determined.

How can we practice approaching the story—in the Bible or in art—so that we don’t become like the chief priests as John depicts them?

It’s about empathy. We make our first judgments by sight when we meet someone. We analyze someone within a few seconds based on how they look or what sort of car they drive or the kind of house they live in. We make all kinds of assessments that don’t have any depth. The empathy of looking—what John Ruskin says about seeing with the soul of the eye—means we have to be careful about how we make judgments. Christ shows that there’s a better way, a way to see truth.

It’s not recorded in scripture, but Lazarus will die again. He may be an old man when it happens, but he will have gone through the trauma of seeing Christ die. He will have known more than many others about the experience of the resurrection of Christ.

The part of the story that’s always frustrated me is that Jesus doesn’t tell Lazarus he’s going to be resurrected. Lazarus goes into death without that knowledge. I hadn’t ever thought about the resurrected Lazarus interacting with the resurrected Christ.

Think of the impact Lazarus would have had on other people when they asked him to share his story. He would have been around; he would have been that witness.

Recently I was part of an exhibition called Angels Among Us at a church in Belfast. The organizers chose 24 artists and gave us each a scripture to work on. I was given the story about the strengthening angel that was sent to Christ in the garden of Gethsemane (Luke 22:43–44). I’d never looked at that story before. An angel comes and strengthens Christ in his anguish. He’s experiencing in a much deeper way the anguish that Mary and Martha experience when Lazarus is at the point of death.

I made a head for the angel and layered it in gold leaf, with bright layers on top of tainted ones so you can see through to the layers that are tainted. The idea is that the angel is taking some of the anguish by being there for Christ, letting it reflect onto him and absorbing it. It comes back down to love: that’s the core of the gospel, the core of Christ’s message, the core of Christ being sent.

If Lazarus was at the crucifixion, he would have been almost like a strengthening angel, a living example of God’s power to resurrect.

Yes. A living example of love and grace.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Called from death.”