Faith, imagination, and the glory of ordinary life

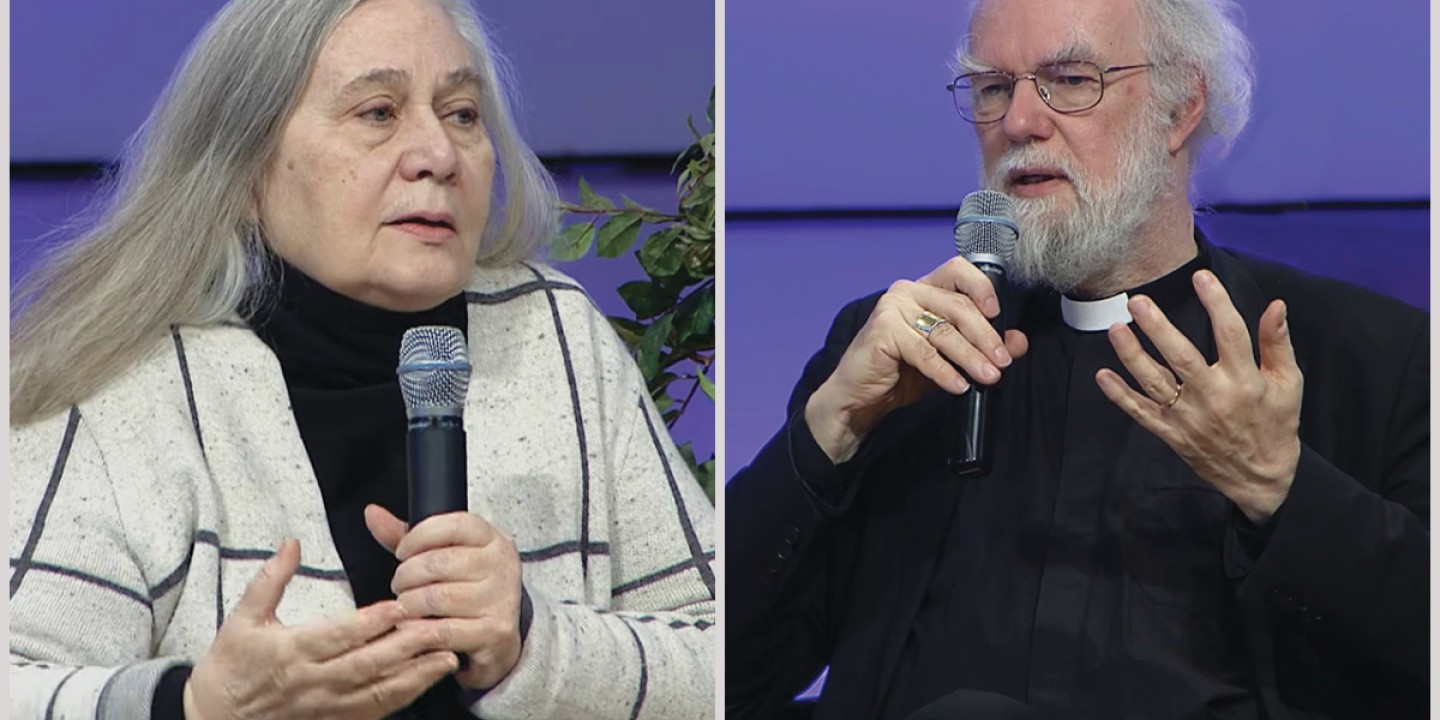

The following conversation between novelist Marilynne Robinson and theologian Rowan Williams took place at Wheaton College in Illinois and was moderated by members of Wheaton’s faculty as part of a conference on the theological significance of Robinson’s work.

You’ve both written or talked about how imaginative work, particularly fiction, provides insight into the divine. How would you articulate that conviction?

Rowan Williams: People often suppose that imagination is Making Things Up. People who write even in a small way as I do know that there’s an element of real discovery in the work of the imagination. You’re generating new questions, new stimuli as you work. I’ve never—to the world’s great relief—written a novel, but I do write poems, and the experience of writing a poem is very often that sense that you half hear something and you know you’ve got to work at it, you know you’ve got to let it unfold, and you don’t quite know where it’s going and sometimes where you thought it was going is absolutely not where it ends up. All of that makes me think that the imagination really is a faculty in us which uncovers something.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Marilynne Robinson: That’s very true. One of the things that is interesting when you become involved in writing a novel is how strongly voices become real to you, so that if you give a person in the novel a word or phrase that person would not use, it rings in an unpleasant way in your mind and you have to go back and fix it. You lose options as the fiction becomes more and more realized.

How can the church be more open to the transformative powers of the arts?

Robinson: Literature is, in a strict etymological sense of the word, subversive. It wants you to think about something in a way that you would not otherwise. The same is true of poetry. And sometimes people who subscribe to goodness in a programmatic way are resistant to surprise. Christianity is subversive in that sense. Christ became a slave. That undercuts cultural assumptions about what is valuable, what the hierarchies are. Art reproduces that great overturning whenever it’s good art.

Williams: I think that also explains why it’s very difficult for the church to commission or control art. Some people come at it this way: “Well, art’s obviously very important—let’s have some Christian artists around the place.” It’s much more a matter of the church so nourishing three-dimensional human minds and hearts that there are people who are touched by that subversive fullness which is grace. It’s about the church being hospitable to difficult voices and difficult images.

Both of you are so interested in language, this special indication of our humanness. What are the chief causes of the degradation of language in public discourse, and how does that degradation impact us?

Robinson: I find that people are actually moved by good language. One of the things that is an affliction is that we condescend to one another. This has bothered me forever. When Abraham Lincoln—a virtually totally uneducated man—wanted to speak to people, he did it with a degree of refinement that is extraordinary by any standard because he had respect for the people he was speaking to.

To whom are we condescending? How have we let ourselves have such negative assumptions about people in general? Democracy cannot survive if we continue to condescend at that level where we don’t give good information, we don’t articulate things with the sensitivity that they require to be articulated if they are going to be meaningful at all.

Williams: I’ll sign up to that. It seems we’ve got some very diverse, rather contradictory tendencies at the moment. On the one hand, there’s what you might call the advertising default setting: I’ve got to sell this to you, so what I need to do is to manipulate your reactions. I need to know which buttons to press. That’s the functional picture of language.

On the other side, strangely—but of course not so strangely when you think that there’s every reason to be suspicious—you have a very suspicious approach to language: “So what are they really trying to say? What are they really putting over on me?” You have a mixture of manipulation on one side and cynicism on the other. That is the perfect storm as far as healthy language is concerned, and it is lethal for democracy in the long run. It’s what creates both a passive and a resentful population.

Robinson: Historically we’ve had moments when we’ve made good democratic actions, created positive things that we live on still, even though in some cases we seem to have forgotten what they were for. The questions for a democratic citizen are “What kind of world do I want to make for the people around me? What kind of reality do I want the people who I call my community to live in? How can I create institutions or support traditions that actually free and enlarge the people around me?”

It’s the solidarity thing again. If you have contempt for people in general, have no articulated aspiration for their well-being, no great interest in protecting dignity, then you don’t design good institutions and traditions in the first place. And this is one of the very negative things that we’re allowing to happen.

To engage with novels requires time, attention, and patience. We’re in a very distracted society. How do we help people value taking the time to engage works of fiction where they can have the experiences you are describing?

Williams: We need a range of disciplines of time taking. We need to encourage one another—encourage the rising generation—probably to do more gardening and more cooking. And then maybe you’ll save the world by gardening and cooking, in the sense that there are some things which are good only if you take time with them. Because we tend to assume, “Well, the quicker the better,” we don’t understand that the good of this activity is the time taken.

That’s all about reconnecting with our own bodilyness in some ways. Unfortunately we have the very ambiguous gifts these days of social media and electronic communication which has privileged rapid interaction. As we all know, there ought to be on every computer a “leave it overnight” button which we press rather than the “send” button.

Robinson: If you read the science that pertains to these things, you find out that humans are infinitely complex. The complexity of any human being is so great as to guarantee that she or he is a unique human being. God made one of you, and it’s up to you to find out what that creation is. What did he make? Who are you? What are you capable of?

One of the things I like considering is that God knows our dreams. We’re asleep, we probably don’t remember them, but God knows them. There’s a beauty in the stream of human thought that you collaborate in and your culture collaborates in, but it’s a singular beauty. If you wrote the best poetry in the world, you still could not sufficiently communicate to anyone else. It’s just between you and God. That’s a splendid privilege. If you think about it in the context of the universe, it is a literally mind-boggling privilege.

A great deal of what people need to do is enjoy themselves. Enjoy being themselves, enjoy finding out what capacities they have, what they love to look at it, what they love to taste. Being uniquely yourself and brilliantly equipped to be yourself, not in the narrow individual sense but in the sense that God knows—that’s the ultimate mystical experience. It requires nothing except that you be respectfully attentive to yourself.

Do you think fiction and the art of the novel teaches us that?

Robinson: I think it should. The better novels, more. The lesser novels, less.

Williams: I think that’s right. I come away from a good novel, whatever it’s been about, thinking there’s more of me and there’s more of others than I ever noticed. There’s a sense that there’s more to the world—a sense of opening up to some sort of depth that I can’t own or get my head around.

The novel Gilead presents us with life in its ordinariness. But in our celebrity-obsessed culture there’s almost a disdain for the ordinary. Could you help us to think about how to give more attention to ordinariness and more value to ordinary life?

Williams: It’s a version of the earlier question about time. Sometimes we want the immediate sense of glamor, gratification, or drama. We can’t understand that the prosaic, the everyday, always accumulates toward glory, because we want the glory now, we want the fix.

I think of Augustine in the Confessions saying, in effect, “The problem isn’t that God’s not here. The problem is that I’m not here.” I’m everywhere but here in this moment, in this particular prosaic, ordinary, physical environment. Part of the function of really effective art is to slow us down and bring us to that particularity.

Robinson: When I think about the ordinary—and that’s a word apparently that I use a lot—I think about the strange miracle of one’s self-ness. When I’ve been away from home for a while, I come downstairs in the morning and I put together what I consider to be the perfect breakfast, which has a lot to do with toast and butter. Combining the sense of the ordinary or the habitual with the sacramental—that’s very strong in my mind.

We talk ourselves into things, like that we’re interested in a celebrity. Very few people over the age of 14 identify in a serious way with a celebrity. But they are distractions, they are the shiny objects. We get told things like “we’re interested in celebrities” and this makes us pay more attention to the magazines at the checkout of the grocery store. But in terms of how people actually live and what they feel, it is: “How do I get along with my children? What do I do with a problem that looks like a looming problem that will require all the understanding that I can muster?” I think people live at that level and maybe take a certain amount of relief from the fact that there is always a new magazine cover.

Williams: This is connected in my mind with the fact that people are often more generous and more free than the media give them credit for being.

Robinson: Absolutely.

Are there spiritual habits or practices that the church should do a better job of teaching us to live inside of—practices or habits that we have avoided that we would do well to return to?

Williams: It’s rhythm again, isn’t it? We’ve lost the sense of creating rhythm in our daily encounter with God. We think sometimes that real encounter with God has to be exceptional, exciting, different, dramatic, and we don’t think of it as simply turning up—and simply turning up in the sense of opening the Bible, reciting a psalm. Simply turning up in the quiet we give to God. We need formation in those things. We need encouragement to develop those habits, but they’re painfully simple.

Robinson: I find that a lot of Protestant churches are embarrassed by things that are traditional. There’s a sense that as things become generationally older, they lose relevance. The chaos that has been caused in a lot of churches by this anxiety is pretty well known.

One of the most important things that churches have to tell people is that you’re a part of the stream of humankind—that if you listen carefully, you can hear something that was said 500 years ago that you will feel as true in the marrow of your bones. We don’t have to scrap the brilliant hymns and the brilliant articulations. It’s not only the fact that there’s a great deal of loss entailed in that, but also a kind of misrepresentation of what we are, which is what any of us is, which is a member of a generation that will have a history and pass away and be displaced by other generations of whom all the same things are true.

Every family, every country, has a complicated history; there is no pristine history. How do we remember well without being overly selective about the great things and forgetting the bad things, but also not letting the negative dimensions of history lead us to have disdain for the history?

Williams: “The truth will set you free,” somebody said. And to accept the truth of the mixed history we all have as communities and as individuals is a key just to growing up. It means that I look at my past self and think, “How could I have thought that? How could I have done that?” But I did and it’s part of me, and it’s part of what God sees, and it’s part of what God works with. Only if it’s brought into the light can it fully be worked with. And the same applies if we look back.

Rather than just say, “Oh, how could they have thought that? How could they have done that in a previous age?”—being contemptuous toward the past—we should say, “Well, like me, these were people with partial perspectives, partial understanding, and they did their best and they did it really badly like me.” And bringing that into the light and acknowledging it about them and with them—I think that’s how we actually live in the communion of saints. We’re great chronological snobs, aren’t we? We love to think how stupid our predecessors were—without realizing that, of course, means we will be thought of as equally stupid by our successors.

Robinson: We need to look more at what we have received that is really of unambiguous value. Abolitionists were the founders of Wheaton College and who knows how many other colleges. This movement was extraordinarily large but is now forgotten. Nevertheless, every one of us feels fortunate to be in such a place and to know that there are places like this all over the country. People intentionally made these places. They made them with intentions that were perhaps higher than ours. Their intentions sustained these institutions and we live in them.

We have a tendency to say of a figure of the past, “Well, he seemed like a very idealistic figure but in fact . . .” It’s as if the “but in fact” cancels out the “he was a very good, productive person in this role in his life.” We’re brutal. We all have to hope that God is a great deal kinder than we are and stop being so eager to find out the most negative thing that you can say about anyone and have the good grace to acknowledge the fact that we have been given extraordinary things. Stop looking for ways to undervalue. Be conscious, be intentional, about valuing what is clearly good and remembering always that it is good by someone’s design as a consequence of any amount of collaboration. We have a habit of thinking that only cynicism is honest—and this is a terrible blindness.

If you could go back to your 20-year-old self and give yourself advice that would apply to them, what would you say?

Robinson: I was such a boring 20-year-old. I basically stayed in my room in college and read books. I cannot regret this for one moment, frankly.

Williams: I think I’d probably say to my 20-year-old self, “Be less anxious, be more grateful.” Being grateful—I think probably that’s the beginning of all wisdom. I’m not sure that when I was 20 I was thankful enough for the world I was in and the people I was with.

This conversation was moderated by Wheaton professors Christina Bieber Lake and Vincent Bacote. A fuller version of this excerpt will appear in Balm in Gilead: A Theological Dialogue with Marilynne Robinson, edited by Timothy Larsen and Keith L. Johnson, forthcoming from InterVarsity Press in April 2019. Questions and Williams’s responses © 2019 by Timothy Larsen and Keith L. Johnson; Robinson’s responses © 2019 by Marilynne Robinson. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press and Marilynne Robinson. A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Faith, imagination, and the glory of ordinary life.”