In aftermath of Nairobi attack, Kenyans seek to prevent harassment of Somalis and Muslims

Community leaders have worked to counter the idea that Muslims are collectively to blame for attacks by al-Shabaab militants.

(The Christian Science Monitor) Abdimalik Anwar was sipping a cup of coffee in Nairobi’s Eastleigh neighborhood on January 15 when a friend called to ask if he had heard the news. A few miles away, militants linked to the group al-Shabaab had stormed an upscale hotel and office complex called 14 Riverside, killing and injuring dozens.

Anwar felt a jolt of fear. In 2013, when the Somalia-based al-Shabaab attacked the nearby Westgate Mall, some Kenyans had turned their anger on the country’s large community of Somalis.

A violent police crackdown swept Somali neighborhoods, and many young Somalis such as Anwar—who has lived in Kenya since he was an infant—endured severe harassment in the streets.

This time, a different conversation emerged.

“Protect Somali people and Muslims in general from the nonsensical harassment that this Riverside thing might cause,” wrote Bryan Ngartia, a Kenyan writer and performing artist, racking up more than 1,200 likes on social media.

Similar messages received similar responses. For Somali community leaders, such showing of solidarity suggested Kenya was changing and that their long campaigns to bridge the divides between the Somali community and its neighbors were finally paying off.

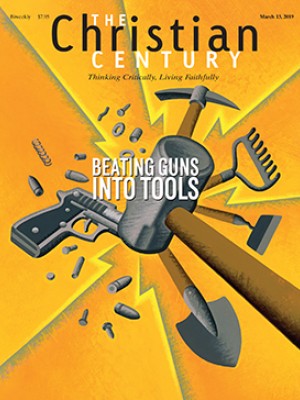

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Somalis began arriving in Kenya as immigrants and refugees in the 1990s, during the beginning of a civil war in Somalia. As the war dragged on, many put down roots in Kenya, and today there is a large community of young Somali Kenyans who have never visited their parents’ homeland. In Nairobi, the community is centered around Eastleigh, a cosmopolitan neighborhood often dubbed “Little Mogadishu.”

Otsieno Namwaya, an Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch, appreciated Kenyans’ supportive responses after the recent attack but remained cautious because of past security campaigns.

In 2013 and 2014, 5,000 Kenyan police and military officers were deployed to Eastleigh as part of a broad counterterrorism mission called Operation Usalama Watch. They carried out raids and arrested thousands, alleging terrorist ties or illegal migration. Many were detained in Kasarani Stadium, where they reported inhumane treatment.

“We saw so many Muslims, young Muslims, being picked up and disappeared or shot dead around Eastleigh and Majengo area of Nairobi and parts of the coast region,” Namwaya said. “There were so many incidents of violations, including arrests, disappearances, killings, extrajudicial killings.”

The campaign sent a message that Somalis specifically and Muslims more generally were collectively to blame for the terrorist attacks, advocates said.

Zakaria, a 30-year-old Somali Web designer who asked to use only his first name, remembers that time well. He was a student living in Eastleigh when the crackdown began and was called a terrorist as he walked down the streets of central Nairobi.

“When a Kenyan person saw me,” he said, “they didn’t see a Somali, they saw al-Shabaab.”

After the recent attack, hundreds of people gathered at the Chiromo mortuary, a short walk from the scene of the crime, where people of many backgrounds had come to confirm the deaths of their loved ones.

“We are mourning together,” said Mohammed Sheikh, who is the member of parliament for Wajir South County. “We are not going to accept anyone to divide Kenyans. We are not going to accept being divided by ethnic lines.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Following Nairobi attack, Kenyans unite to protect Somalis and Muslims.”