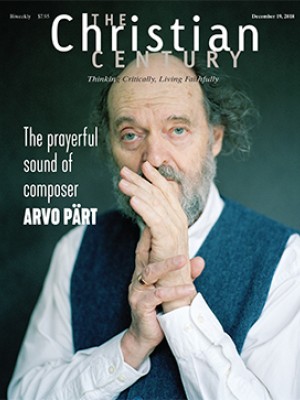

How Arvo Pärt speaks prayer into a secular world

The composer sees his music as an interplay between suffering and consolation, loss and hope.

In a recent address, Arvo Pärt told his audience: “I apologize, but I cannot help you with words. I am a composer and express myself with sounds.” If anything, his reticence is on the increase: after the swarm of attention that accompanied his 80th birthday in 2015, the world’s most-performed living composer stopped giving formal interviews altogether.

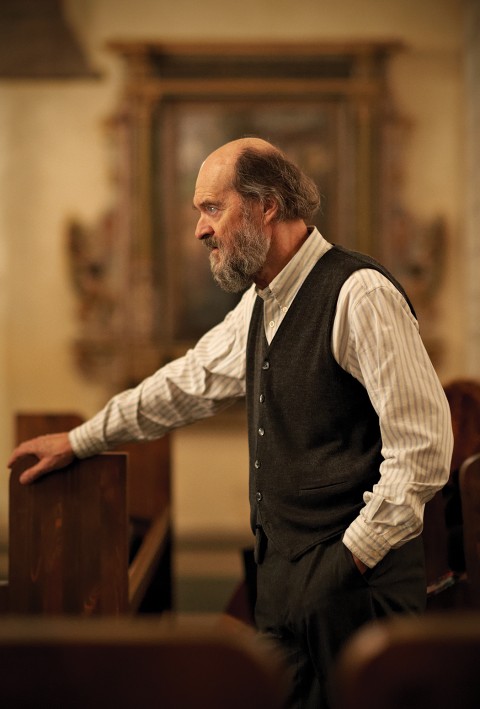

If he says little about his work, he is even more taciturn about how it relates to his faith, frustrating those of us who would want to explore his ideas on that subject. Yet a few scattered statements tell us a great deal: he has said that if people wish to understand him, “they must listen to my music,” but if they wish to know his philosophy, “they can read any of the Church Fathers.” He also admits that he is “more at home in monasteries than in concert halls.” This man, whose work reaches audiences of a diversity beyond that of any other classical composer, is steeped in the church fathers and cherishes monastic sojourns.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As Christians have scrambled to regain the attention of a wider society once claimed by figures like Reinhold Niebuhr or Paul Tillich, this composer of quiet, somber music has reached audiences they couldn’t have dreamed of, using the untrendy words of Christian spiritual authorities: all but a tiny number of his 90-odd compositions since 1976 are settings of biblical texts or Christian prayers. He draws regularly on the Psalms, on classical scriptural prayers (the Nunc dimittis, the Magnificat), and on sayings of Jesus (“I am the true vine”). He has composed a monumental St. John Passion and several settings of the mass.

The question is: Why are people listening so avidly? The same audience that would instinctively tune out anything with a whiff of Christian sensibility, that would normally be repulsed by pious petitions to Jesus or Mary for the forgiveness of their wretched sins, is held rapt by these very prayers when Pärt speaks them through his compositions.

A classical music aficionado will readily identify Arvo Pärt as a “sacred music composer.” (That was, in fact, how a Sunday Times crossword puzzle clue identified him a few years ago.) His wider audience, who may have come to him by way of the ECM label (which had issued almost exclusively improvised music until it began recording Pärt), film soundtracks, or perhaps DJ sets, are uninterested in placing him within a “sacred music” canon, but will inevitably remark on his music’s “spiritual” quality—whatever they may mean by that word. To his large “spiritual but not religious” audience, the transcendence of Pärt’s work speaks entirely on its own terms.

While it would be impossible to plumb the exact place that the music and its texts are reaching within people’s hearts, minds, spirits, or bodies, a closer look into the composer’s life and his compositions may give us some insight into the nature of his music’s beauty. Because that is finally what draws his listeners in.

Born in Estonia in 1935 to an Orthodox father and a Lutheran mother, Pärt’s Christian roots lay essentially dormant until his early adulthood, when music played a formative role in their reinvigoration. The Western European early classical music that he came to love, and which influenced him as a composer, was in most cases set to sacred texts. In time the composer came increasingly to see that these textual settings were inextricable from the music itself. Thus began a spiritual search through ancient and modern texts from Eastern and Western Christian traditions that would lead to his joining the Orthodox Church in 1972.

His journey to the Orthodox Church through music, text, and personal encounter took place during a complex time in communist Estonian history, when any church affiliation on the part of an Estonian was construed as an act of political defiance of the militantly secular USSR. So even as Pärt came increasingly to reveal his spiritual search in his music, beginning with his 1968 composition Credo, it became ever more costly to his personal and creative freedom. He was eventually forced to emigrate from Estonia in 1980. Yet even during this politically fraught period, Pärt continued to deepen his spiritual life.

Much of this process took place through his close, repeated reading of ascetical literature, including the 15th-century Imitation of Christ and the 18th-century Philocalia. He also read 20th-century spiritual authors, among whom St. Silouan of Mt. Athos (1866–1938)—as portrayed in the writings of Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov)—was especially influential. Silouan’s tumultuous journey into the depths of despair—and humility—left an indelible mark on Pärt’s inner life. He later developed a close relationship with Sophrony, by then the staretz or spiritual leader of the monastic community he had founded in England. Sophrony passed away in 1993, but not before Pärt had dedicated his Silouan’s Song to him and his community.

Pärt’s spiritual journey during the 1970s coincided with the period of his most acute creative crisis and close to a decade of compositional remission: between 1968 and 1976 he composed almost nothing. With hindsight, though, what seemed to be barrenness during this so-called silent period emerges as a period of gestation. Music and faith were intertwined in moving the composer not only out of a creative deadlock, but into something entirely new.

This period of fertile hibernation was also when Pärt found himself drawn to 15th- and 16th-century Franco-Flemish composers and Gregorian chant. The music’s effect was twofold. Its sound—its purity, simplicity, honesty—came increasingly to awaken a new musical vocabulary for him, such that he sought a similarly unfettered manner of sonic expression for his own music. But this wasn’t just a matter of imitating a reductive, pristine sonic effect: it was part of a religious awakening. What he was listening to was, for the most part, a sacred music whose texts were inextricable from its tonality.

Furthermore, Pärt realized that this relationship between word and sound was mediated through faith and devotion. Inevitably, the music emanated from a space of contemplative prayer, and he knew that in order to really enter into it, and to glean its value and its lessons, he had to pursue his own life of prayer. As he said to me once in conversation, “Only through prayer is it possible. If you have prayer in your hand like a flashlight, with this light you can see what is there [in the music].”

And so it was that his compositional standstill ended in 1976 with a string of works that were disarmingly simple, quiet, yet potent. Among them: Für Alina, Pari intervallo, Fratres, Missa syllabica. These signaled the birth of a new musical style—tintinnabuli—that remains Pärt’s main creative topos to this day. Tintinnabuli—meaning “little bells”—is the name he gave to his compositional method whose foundation is two basic lines: a melody and a triad. When these sound together, they do indeed ring like little bells. (For a good example of that special resonance, listen to his seminal tintinnabuli work, Für Alina.)

His earliest pieces in that style alternate between wordless arrangements and settings of prayer, liturgy, or scripture. From 1980 onward, virtually none of his works lacked a basis in sacred text. A coalescence was becoming clear to him—one that remains with him to the present day—between music/beauty and the faith/prayer expressed through specific sacred texts. The music emanating from this realization manages to convey something beyond itself, something that commentators of a wide variety of religious persuasions have associated with stillness, reverence, and purity.

It would be impossible to overstate the importance of text to Pärt’s compositions. In most cases, the words literally give the music its shape: their syllables, accents, and punctuation are meticulously reflected in the music’s rhythmic and melodic structure, whether they are sung or, as is sometimes the case, “played” by the instruments without being vocalized.

“The words write my music,” says Pärt, who avers that the resulting arrangements are “merely a translation.” For him, the sound is determined by “the Word . . . The Word, which was in the beginning.”

In effect, Pärt submits himself in an unswerving obedience to the text. In an extensive interview in the book Arvo Pärt in Conversation, he asks people to receive the texts “not as literature or as works of art but as points of reference, as models.” The Psalms, he says, “are not just poetry. They are part of the Holy Scripture. . . . They are bound to universal truths, so do they touch upon intimate truths, purity, beauty, that ideal core to which each human being is bound!”

In short, he regards these texts as true. The ancient Christian apologists told us that truth, beauty, purity, essence, by any name and wherever they are found, should be identified with Christ the Logos/Word. They drew on Paul’s exhortation to think on whatever is honorable, pure, lovely, and gracious (Phil. 4:8), ostensibly whether or not it has an identifiably Christian character.

The “Pärt phenomenon” is in some ways the reverse: taking explicitly Christian words and disseminating them into the world in the form of the pure, the lovely, the gracious, thus mediating them to an audience that might otherwise be leery. Although the music does not sideline Christ, its effect is no longer entirely dependent on the texts’ openly Christian character.

Whatever he’s doing, it seems to be working. His musical translations of scriptural and liturgical words—about God, Christ, Mary, sin, and salvation—that normally would have bounced off his audience’s protective armor instead insinuate themselves into his listeners’ spiritual lives, as testified through countless reviews of Pärt’s recordings and performances.

But something is happening musically as well, both apart from the texts and also through them: the music reaches people at their emotional (which is not to say sentimental) inner core. Pärt speaks of his compositions as a perpetual interplay between suffering and consolation, loss and hope, “sins, and the forgiveness of sins,” as if there were two voices that together form one. His audience has been known to describe their experience of the music in similar ways.

The Icelandic singer-composer Björk has said that she hears two voices in Pärt’s work: “Pinocchio,” making mistakes, bearing and inflicting pain; and the other “Jiminy Cricket,” whose role is both to comfort the erring one and to keep him in line. Another author compared these voices to a toddler learning how to walk and a mother accompanying it at every step with outstretched arms, ready to correct and catch it: one voice is potentially straying, the other is there gently to right its way. When Michael Stipe of the band R.E.M. called Pärt’s work “a house on fire and an infinite calm,” he identified the paradox of simultaneous turmoil and stillness, neither one fully expressed without the other.

The listener is held between the extremes of despair and bliss, within the living tension between those poles. This is more than an artistic paradox. The Christian worldview is based within a particular configuration of joy and sorrow. “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (John 12:24). Flourishing life is predicated upon death, yet the final word is never death. It is life. That conviction is pervasive within what Orthodox call the “bright sadness” of Christianity: as much as joy is intertwined with sorrow, sin, and corruption, the final word will be stillness, forgiveness, redemption, hope.

That pattern is reflected in Pärt’s music, where the word of hope and forgiveness is uttered from the depth of a soul that evidently knows its opposite. The word of hope is thus eminently more credible, true to life, and meaningful. Take for example Tabula Rasa, a composition from 1977. Its second movement, titled “Silentium,” is frequently invoked in film scores and commentary as a sonic icon of stillness, of solemn quiet. But its tranquil spirit doesn’t exist on its own. Not only is it infused with a somber, sober character, it also follows directly after a tumultuous passage from the preceding movement that could almost be called ferocious. It is anything but calm, but it paves the way for a sublime, solemn stillness. Few if any Pärt compositions could be considered univocal. They are a balance, true to life, of the bitter and the sweet, utterly devoid of sentimentality, but leaving their hearers with the sense of being heard in their sorrow, and consoled in it.

The main themes of Pärt’s music are evident in his major work Adam’s Lament. Composed in 2010, it is a setting of the eponymous spiritual meditation of St. Silouan the Athonite. Pärt sets about a quarter of this lengthy text to music, focusing on its opening stanzas. The resulting composition describes an emotional arc which begins with the joy that Adam feels in Paradise, moves through Adam’s bitter grief when he is cast out and his reverent desire of regaining a still fairer Paradise, and ends with the realized hope of salvation at the cross of Christ. These are the words Silouan gives to the grieving Adam:

I cannot forget Him for a single moment,

and my soul languishes after Him,

and from the multitude of my afflictions

I lift up my voice and cry:

“Have mercy upon me, O God. Have mercy on Thy fallen creature.”Thus did Adam lament,

and the tears steamed down his face on to his beard,

on to the ground beneath his feet,

and the whole desert heard the sound of his moaning.

The beasts and the birds were hushed in grief;

while Adam wept because peace and love were lost to all

men on account of his sin.

Silouan’s words express a spirit of reverence and longing for God rather than self-pity (or worse, self-justification). The only glimmer of hope offered in the text of this musical setting resides in its concluding prayer: “Be merciful unto me, O Lord! Bestow on me the spirit of humility and love.” These words, on their own, are hardly the full realization of hope and comfort. But the music to which they are set—a reverential hush, almost a whisper, from just a few of the choir’s voices—somehow imbues them with a sense of humble conviction that God will answer that prayer. In this way Pärt presages the consolation that is made explicit later in the text.

By giving us Adam, as the representative of the whole of humanity in its brokenness, Pärt invites us to identify with him in his regret and repentance as well as in his glimpses of redemption through humility and love. The universality of Adam’s state and his hope is not lost on Pärt’s listeners, especially when they are brought face-to-face before the text itself. I attended a performance of this work where Silouan’s words, in English translation, were projected onto the concert house wall as they were being sung in its original Russian. I watched as many in the audience of New York cultural illuminati around me, as well as my own teenaged children, literally wept in recognition of their own lives in Adam’s.

The last thing to say about Pärt— before going and listening to his music, with or without reading the accompanying texts—is that, although I would never seek to invade his inner self, or make of him a mystic or a holy man as some try to do, I see two critical elements in his life that have lent power to his music: the quest for inner silence and the pursuit of inner purity.

Pärt wrote, in his diaries, with tacit reference to the passage from John 12:24 cited above: “Before you can be resurrected, you must die. Before you say something, perhaps you should say nothing.” We have seen how that was mirrored in the composer’s life, where the tintinnabuli compositions for which Pärt is best known came after an eight-year period of near-dormancy. Something needed to be born, but that birth had to be preceded by a deep-level cleansing, effectively a death.

Pärt’s silent phase was not a voluntary reclusion: it was brought on largely by creative factors outside his control. But the stillness that this phase evinced in his music—and in his person—could then be taken up into a chosen, consciously cultivated inner stillness.

In recent years, Pärt has gradually become more public with some of the diaries he kept during and after his silent period. The pithy sayings that he recorded in his notebooks reveal an increasing awareness of a profound fact: if his music is to be a translation, if it is to mirror the sacred words, the mirror must be clean. The music mustn’t clutter, add to, or detract from the words: it must be transparent to them. And for that to happen, the composer must himself become transparent, pure.

A frequently cited story of Pärt’s is about a monk who told him that there is no need for him to write new prayers. “All the prayers have already been written. You don’t need to write any more. Everything has been prepared. Now you have to prepare yourself.” He has taken these words to heart, and into his life. This turn inward, a realization that the only earth one can properly till is that of one’s own heart, is reflected in these journal entries:

Living according to God’s commandments is literally a creative activity. I am not telling you this as though I myself might have accomplished something here. But I am completely persuaded that every step is then a discovery, through tears and sweat, of course: a chain of losses and findings, of self-transcendence, of falling and getting up again.

The composer is an instrument, and in order for the instrument to sound correctly, it has to be in order. One should start with this, not with music.

What of all this is conveyed to Pärt’s widely diverse listenership? Books, essays, and Internet commentary about him can only give us clues. People certainly aren’t hearing a sermon or Christian apologia, or else they would have left his music by the wayside. Whether or not they are reached directly by the sacred texts themselves, perhaps they can sense that the spirituality—the purity and transcendence—that they encounter within his compositions can be arrived at only through faith, stillness, and ascetic discipline. And that is no small thing.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The Word made music. ”