Catholics and lawmakers respond to Pennsylvania report on clergy sexual abuse

Pope Francis wrote, "We showed no care for the little ones; we abandoned them."

Public outcry was swift when Pennsylvania officials released a report last week detailing accusations that Catholic priests had sexually abused more than 1,000 children since the 1940s while church officials shielded the abusers.

The grand jury report, which is more than 1,300 pages long, is the result of an 18-month investigation spearheaded by state attorney general Josh Shapiro examining six of the state's eight dioceses.

The report exposes a “systematic cover-up by senior church officials in Pennsylvania and the Vatican,” Shapiro said upon its release. “There have been other reports on child sex abuse in the Catholic Church, but never on this scale.”

Days later the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops announced a new plan to address the “moral catastrophe” in the church. The USCCB's president, Daniel DiNardo of the Galveston-Houston Archdiocese, said leaders “need to develop and widely promote reliable third-party reporting mechanisms” for allegations made against church officials, and he noted that any effort should rely heavily on Catholic laypeople.

“We are faced with a spiritual crisis that requires not only spiritual conversion, but practical changes to avoid repeating the sins and failures of the past that are so evident in the recent report,” DiNardo wrote.

A statement from Vatican spokesman Greg Burke emphasized “the need to comply with the civil law, including mandatory child abuse reporting requirements.”

Pope Francis released a letter today, writing that “no effort must be spared to create a culture able to prevent such situations from happening, but also to prevent the possibility of their being covered up and perpetuated.”

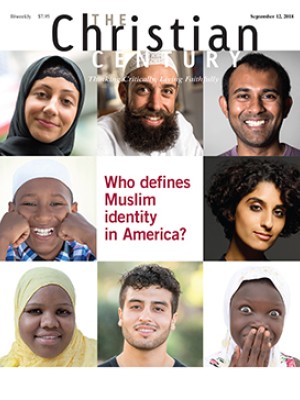

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“With shame and repentance, we acknowledge as an ecclesial community that we were not where we should have been,” he wrote. “We showed no care for the little ones; we abandoned them.”

The pope called for “every one of the baptized” to be involved in changing church and society to ensure the safety of children and adults.

Questions remained as to what effect, if any, the report will have on American Catholicism or whether it will impact how states prosecute clergy sexual abuse in the future.

James Martin, a Jesuit priest and editor at large at America Magazine, predicted fallout from the revelations could be as far-reaching as what followed the Boston Globe’s 2002 Spotlight investigation, which unearthed comparably horrifying allegations in Massachusetts.

“We can already see the convulsive effect it has had on the church in this country,” he wrote by email. “People are nauseated, and that includes people far from Pennsylvania. … People are more disgusted than they were in 2002, if that's possible.”

Several Catholic laypeople interviewed spoke of reducing or ceasing financial contributions to the church, canceling baptisms, and attending mass less or not at all. Suzanne Gillies-Smith, who grew up in Pennsylvania, recalls vomiting repeatedly after reading reports in 2011 of abuse in her hometown. She continued attending mass after that but did not plan to go after the release of the report.

“The thought of even looking at a person in authority within the church makes my stomach uneasy,” she said. “The one thing I know I could do is affirm that I believe all of the victims, known and unknown. . . . It is those victims who represent God here, not the hundreds of priests who abused them.”

The grand jury investigation relied heavily on records documenting the abuse that sat “just feet from the bishop’s desk,” according to attorney general Shapiro.

The 23 grand jurors emphasized that “while the list of priests is long, we don't think we got them all. . . . We feel certain that many victims never came forward, and that the dioceses did not create written records every single time they heard something about abuse.” While a few priests in the state are facing charges, the jurors also noted that “as a consequence of the cover-up, almost every instance of abuse we found is too old to be prosecuted.”

Four reforms are outlined in the report: eliminating the criminal statute of limitations for sexually abusing children, creating a longer civil window in the state so older victims can sue for damages, clarifying the penalties for continuing to fail to report child abuse, and disallowing civil confidentiality agreements from covering communications with law enforcement.

Meanwhile, the six dioceses have pledged to publish the list of priests accused of sexually abusing children in their region, and some, including Greensburg and Harrisburg, already have. Ronald W. Gainer, bishop of Harrisburg, has ordered that the names of all of its bishops since 1947—the beginning of the grand jury's investigation—be stripped from all church buildings in the diocese.

As Pennsylvania lawmakers began addressing the recommended policy changes, other states considered their own investigations. Several state attorney general offices said they were reviewing the Pennsylvania grand jury report and investigating possible courses of action.

Mitchell Garabedian, a lawyer for child abuse survivors who played a key role in the Globe’s Spotlight investigation, said changes to state laws could have a major impact.

“There need to be amendments in the statute of limitations so that justice can be obtained, transparency can be accomplished, and victims can try to heal,” Garabedian said.

A version of this article, which was edited August 28, appears in the print edition under the title “Catholics and lawmakers respond to state report on clergy sexual abuse.’”